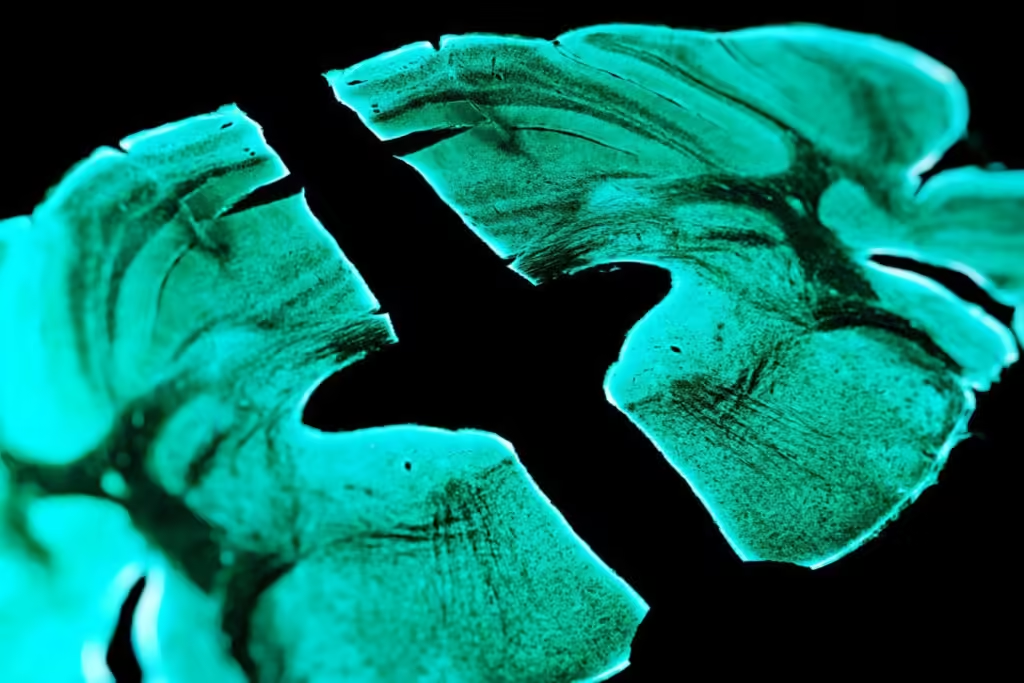

A slide showing part of a mouse brain

Stu Gray / Alamy

A newly identified brain pathway in mice may explain why placebos, or interventions that are not supposed to have a therapeutic effect, can relieve pain, and the development of drugs that target this pathway could lead to safer alternatives to painkillers such as opioids.

If someone unknowingly takes a sugar pill instead of a painkiller, they still feel better. The placebo effect is a well-known phenomenon in which people’s expectations reduce symptoms even in the absence of an effective treatment. “Our brain can solve the pain problem on its own, based on the expectation that a drug or treatment might work,” says Gregory Scherer of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

To understand how the brain does this, Scherer and his colleagues recreated the placebo effect in 10 mice using a cage with two chambers: one with a blazingly hot floor and the other with no floor. After three days, the mice learned to associate the second chamber with pain relief.

The researchers then injected molecules into the animals’ brains that caused active neurons to light up when viewed under a microscope, and then returned the animals to their cages, but this time they heated both floors.

Although the two chambers were now equally hot, the mice still preferred the second chamber and showed less symptoms of pain, such as licking their paws, while they were there. They also showed more neuronal activity in the cingulate cortex, a brain region involved in processing pain, compared with nine mice that had not been conditioned to associate the second chamber with pain relief.

Further experiments revealed pathways connecting these pain-processing neurons to cells in the pontine nuclei and cerebellum, two brain regions not previously known to play a role in pain relief.

To confirm that this circuit relieved pain, the researchers used a technique called optogenetics, which switches cells on and off with light. This allowed them to activate the newly discovered neural pathway in another group of mice that were placed on a hot floor. On average, these mice waited three times longer to lick their paws than mice that didn’t have the circuit activated, indicating they felt less pain.

If this neural pathway can explain the placebo effect, “it would open up new strategies for drug development,” says Luana Colloca of the University of Maryland, who was not involved in the study. “If we had a drug that activated the placebo effect, that would be a great strategy for pain management,” Colloca says.

“The obvious caveat is that the placebo experience in humans is obviously much more complex,” Scherer says, but he believes these findings apply to humans because rodents and humans have very similar pain pathways.

topic: