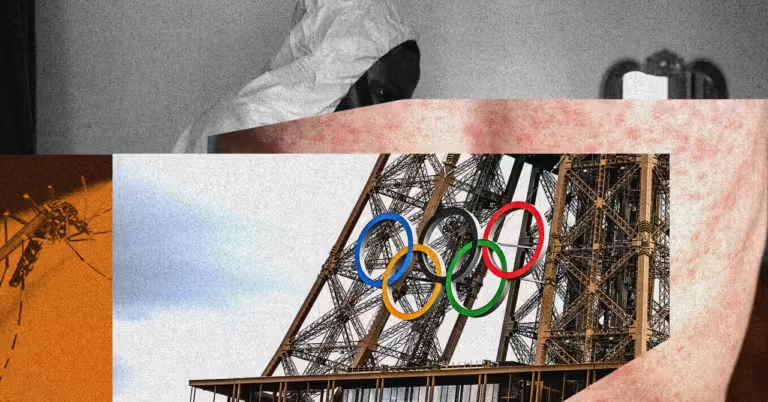

every time When it comes time for the Olympics, there seems to be another disease threatening the games: Zika at the 2016 Rio Olympics, COVID-19 at the postponed Tokyo Olympics, and now this summer at the 2024 Paris Olympics? You can choose which comes first. Officials are working to contain both dengue fever and measles, both of which are on the rise in France and many other countries.

Millions of people from around the world will flock to the host city during the Olympic and Paralympic Games this summer. French authorities are preparing to welcome more than 15 million tourists to the country. That’s a huge influx of people, even for a capital city used to mass tourism, where nearly 40 million people visit Paris every year. Some will bring infectious diseases with them, and those without adequate immunity risk catching something during their stay. Dengue fever and measles are already problems in Paris, and authorities are considering ways to limit the possibility of the Olympics becoming a super-spreader event.

“The risk of a dengue epidemic is very difficult to contain,” explains Anna Bella Faille, a medical entomologist at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. The virus is transmitted from person to person by mosquitoes, and in France the invasive Aedes albopictus mosquito is the culprit. Aedes albopictusRising temperatures exacerbate the mosquito problem, with Europe’s hot summers creating ideal conditions for mosquitoes to breed: “The eggs are very resistant and the mosquito’s metabolism speeds up in the heat. They mature faster and therefore bite faster.”

In France, the Tiger Mosquito is not new: it appeared in the south in 2004 and has been present in Paris since 2015. Native to Asia, this mosquito lays eggs in still puddles that can hatch weeks later, even after the water has evaporated. This is how it spread across Europe, first arriving in Genoa, Italy, and then in France.

But dengue is a relatively new problem. Epidemics of the virus are raging in tropical parts of the world (an estimated 10 million cases worldwide this year, with South America and Southeast Asia heavily affected), and cases are surging in France. Between January 1 and April 30, 2024, health authorities recorded 2,166 cases, compared with an average of just 128 over the same period over the past five years. Most of the cases this year have been imported from the overseas French territories of Guadeloupe, Martinique and French Guiana, where outbreaks remain, but the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has recorded several cases in Europe this year, including in France.

This highlights the risk of hosting international gatherings at a time when cases are surging around the world: if this leads to an increase in imported cases in Paris, the large numbers of Aedes albopictus mosquitoes could spread the virus within the country.

Most infections are asymptomatic or cause only a mild fever, but some people become seriously ill and may die. There is no specific treatment for the virus, and few people in Europe have immunity to it from previous infection. A vaccine has only become available in recent years and is offered only in a few countries with high infection rates.