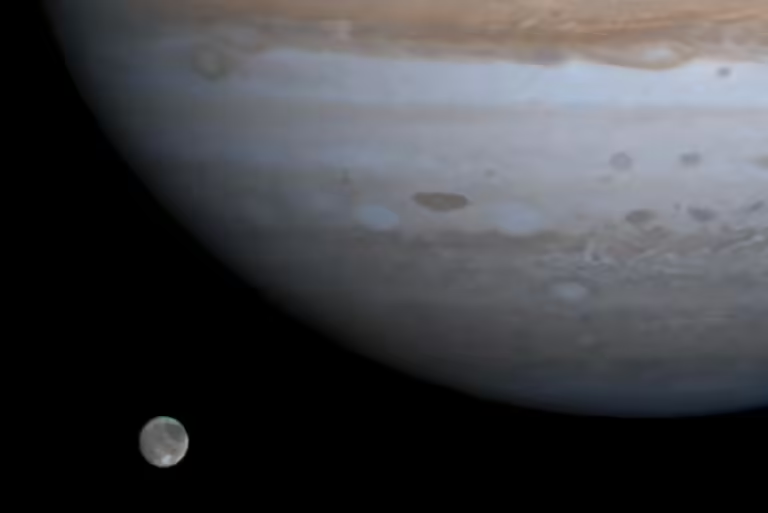

This image taken by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft shows Ganymede, the solar system’s largest moon, and Jupiter.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

A massive impact billions of years ago may have dramatically changed the orientation of Jupiter’s largest moon, Ganymede.

Takayuki Hirata of Kobe University and his colleagues studied Ganymede’s vast rift structure, a series of concentric grooves that are thought to be the remnant of the largest impact structure in the outer Solar System.

The centre of the groove system is nearly aligned with Ganymede’s tidal axis (an imaginary line that runs from the centre of the side of the moon that always faces the planet towards Jupiter), which leads the researchers to speculate that the impact that created the grooves may have caused a massive redistribution of mass, reorienting the moon.

Through simulations, the researchers determined that the impactor was likely about 150 kilometers in diameter — significantly larger than the estimated diameter of the impactor that wiped out the dinosaurs on Earth, which was about 10 kilometers.

If such an asteroid were to hit Earth, “it would be a global sterilization event, a bad day,” says Andrew Dombard of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

When the asteroid struck, it would have broken off Ganymede’s icy crust and plunged into the liquid ocean below, creating a temporary crater and blasting huge amounts of material across the moon’s surface.

As it settled, a thick layer of ejecta formed around the impact site, creating a region where the extra mass strengthened gravity. Over time, the anomaly could cause Ganymede to reorient so that the impact site is aligned with its tidal axis, according to the simulations.

Ganymede’s grooves are thought to be remnants of an ancient impact structure.

NASA/JPL/Brown University

Hirata and his team compared this process to events on Pluto, where a large impact created a basin called Sputnik Planum and caused the dwarf planet to change direction.

But while the Ganymede impact likely had a major impact on the moon’s early history, a lack of good data on the frigid world’s gravity and topography complicates estimating the size of the impacting object, Hirata says.

Dombard says the model used in the paper doesn’t take into account some of the complexities of Ganymede’s unique ice structure. “I think it’s a pretty good model to prove that this process can happen, but I don’t necessarily trust the numbers,” he says.

topic: