This article is part of the Scientific American column “The Science of Parenting.” Go here.

In our efforts to keep our children safe, healthy and happy, it is essential to detect and treat developmental disorders and other conditions early. For this reason, pediatric medicine emphasizes the importance of screening for everything from developmental delays to emotional disorders to autism. Unfortunately, screening results are not always reassuring. If you receive a “positive” result, such as autism, on a screening questionnaire, you may panic. What does this result mean, and why might a doctor think your child has autism?

Ultimately, these screening results don’t provide a simple “yes” or “no” answer as to whether a child has a disease. Identification depends heavily on an estimate of how common the disease is. Detecting rare diseases such as autism is much harder than anyone would like. Parents should know this when they hear about their child’s score. To understand why, you need to know a few basic facts about the science of screening.

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

In simple terms, Screening Questionnaire A screener is a standardized set of questions designed to identify or predict one or more conditions, or underlying health or quality of life issues. For example, an autism screener typically includes questions about behaviors known to be early signs of autism, often focusing on how a child communicates. Each answer is usually scored; for example, a “yes” answer is scored as 1 and a “no” answer is scored as 0. Questions may be scored by comparing a child’s results to those of children of the same age, particularly for developmental milestones. In either case, the answers are combined to generate a total score.

Most screening questionnaires have a threshold, or “cut score.” Scores above this threshold are considered positiveWhile medical professionals are familiar with this language, it can be confusing for patients. positive The results almost always indicate a risk, such as a higher chance of developing autism or other disorders.

How do we know that a positive score indicates a higher chance of a particular disease? When scientists describe a screener as “validated,” this is what they mean. Ideally, studies have been done that compare screening scores with the results of highly accurate independent assessments. If the studies demonstrate that children who screen positive are more likely to have a disease than children who screen negative, the screening questionnaire can be used to validate the results. Diagnostic accuracyIf this questionnaire can identify children who are likely to develop the disease in the future, Predictive validity.

Appropriate screening questionnaires and medical examinations are also expected to be helpful. Estimating Probabilities Are you experiencing symptoms? Let’s take a closer look.

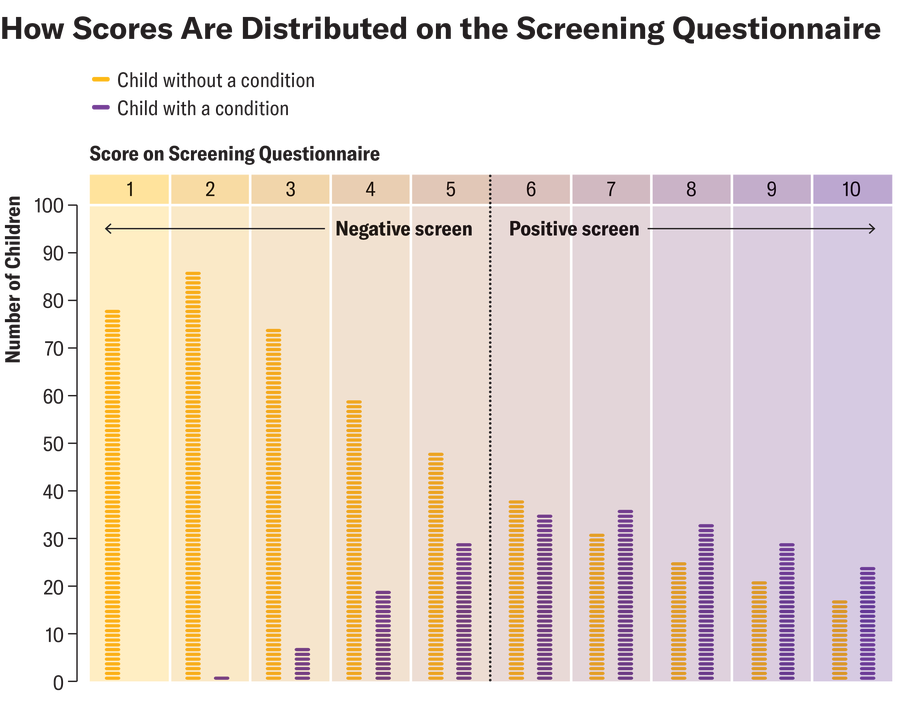

Imagine hundreds of parents completing a “validated” screening questionnaire designed to detect general developmental and behavioral problems, not just autism. Let’s say that one in three children has the developmental or behavioral disorder you want to detect (this is a high estimate, but not outside the realm of possibility). The graph below shows the number of children with and without disabilities who received each screening score.

Amanda Montañez; Source: Chris Sheldrick (data)

Of the 289 children who tested positive, with a threshold score of 6 or higher, 157 had some kind of disease. Therefore, it is estimated that 54% of children who tested positive had some kind of disease. Scientists say this is Positive predictive value, Or PPV. This seems pretty simple: if the screen is positive, there’s a 54 percent chance that your child has the disease, right? But wait. There are at least four caveats to keep in mind:

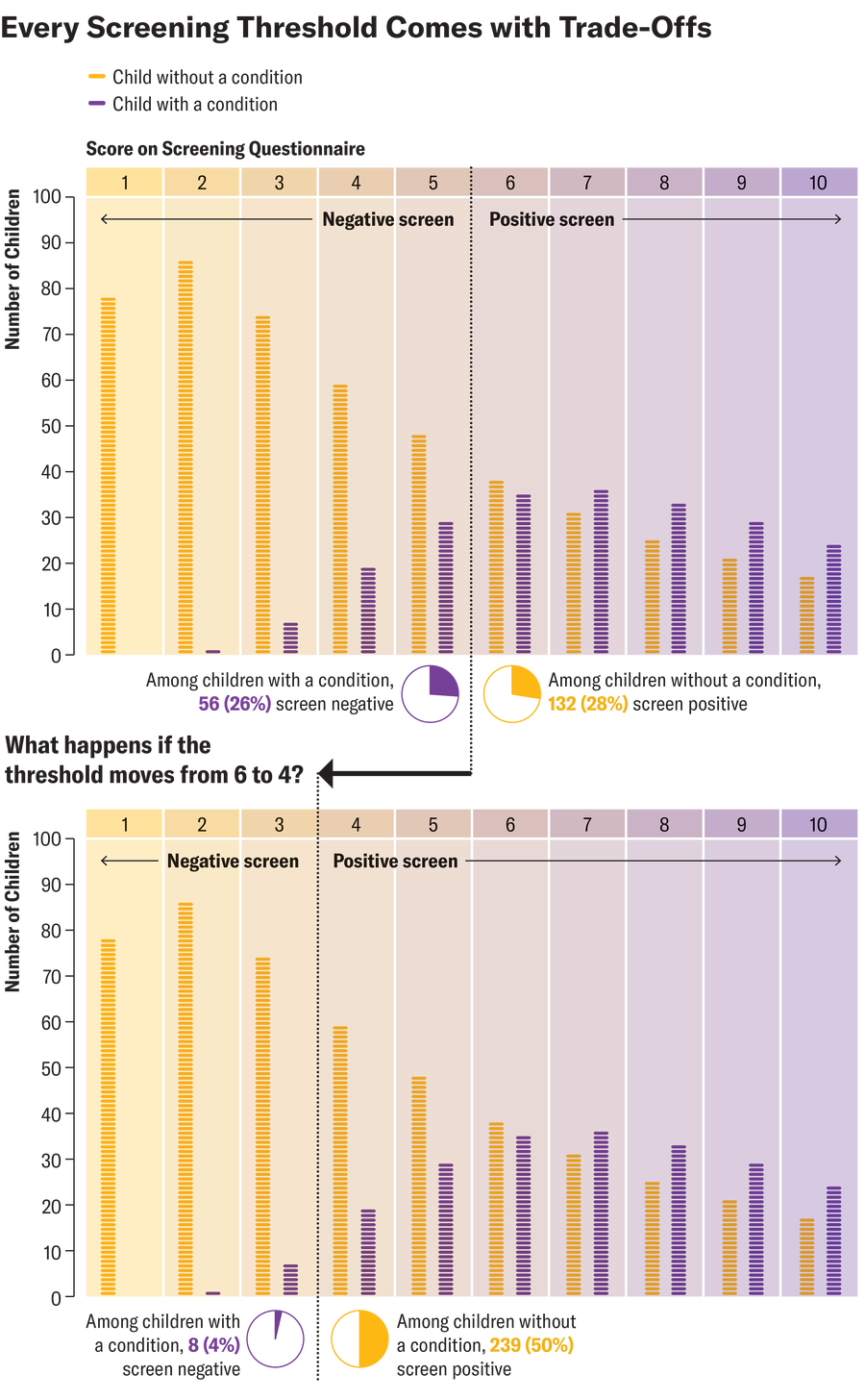

First, no matter how scientifically based these questionnaires are, all screening thresholds have trade-offs. On the one hand, with a threshold score of 6 or greater, 26 percent of children with disease will screen negative. Someone concerned about underdetection may want to lower the threshold; if we change the threshold to a score of 4 or greater, most children with disease will screen positive. On the other hand, in this example, 46 percent of children who screen positive with a threshold score of 6 or greater do not have the disease. Someone concerned about the burden on families may want to raise the threshold; in that case, a score of 6 would no longer be considered positive.

Amanda Montañez; Source: Chris Sheldrick (data)

Second, given the trade-offs in screening thresholds, it is worth considering the screening score itself. In this example, a score of 6 or higher indicates a positive screen result. Of the 73 children with a score of 6, 35 have some disease. This is 48 percent, a lower accuracy than the positive predictive value of 54 percent. This situation is not uncommon. The PPV is average If the screening score is positive, the PPV is Overestimate Probability of a screening score close to the threshold and Underestimating Probability of very high screening scores.

Amanda Montañez; Source: Chris Sheldrick (data)

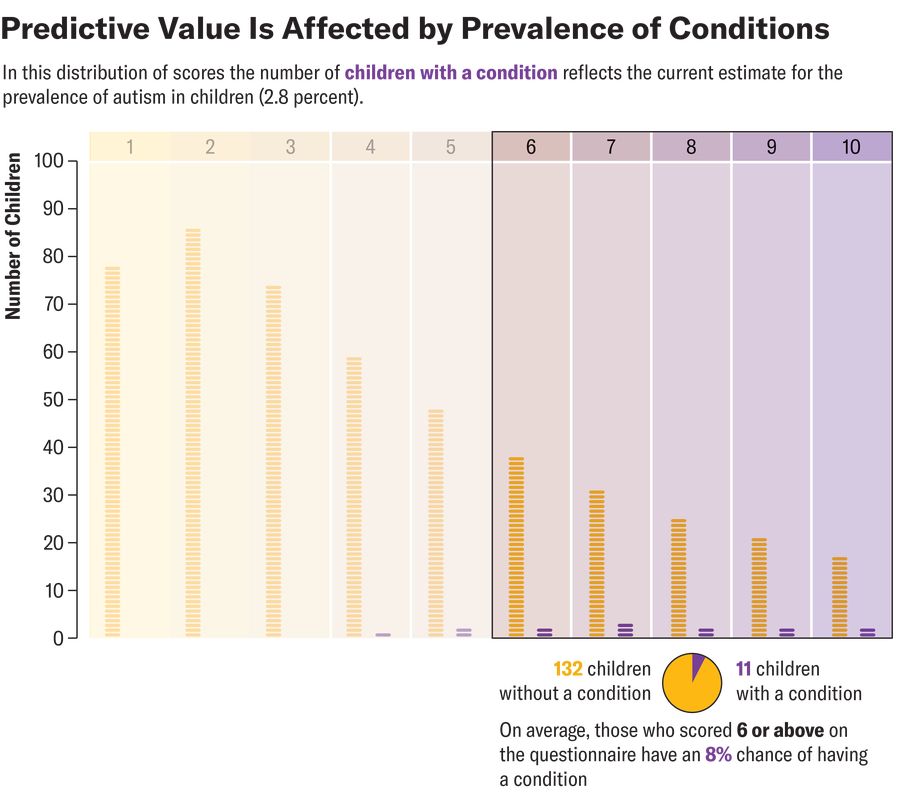

Third, predicted probabilities are heavily influenced by prevalence, or the proportion of children in a population who have the condition. All of the examples above use the same screener — the same proportion of children who screen positive for a disease, and the same proportion who screen negative. However, prevalence makes a crucial difference. If the prevalence of a child’s disease is 2.8 percent (the current estimate for autism), and a child scores 6 or higher positive, then there is only about an 8 percent chance that the child has the disease.

Amanda Montañez; Source: Chris Sheldrick (data)

One way to understand this is that when prevalence is low, there are many non-autistic children for every one autistic child. For each of those non-autistic children, there is some (but unlikely) chance that the screening result will be a “false positive.” When prevalence is low, even with an accurate screening test, the number of “false positives” can dwarf the number of “true positives.” Frankly, this surprised me when I first learned about it, but all such tests are affected by prevalence in this way. Rare events are not easy to predict (for example, if you test positive for the flu, you are less likely to get sick if it is not flu season).

Finally, there’s a reason I put the word “validated” in quotes. No matter how much research there is to back up a survey, it’s never perfect, and we should always question how past research applies to kids growing up in a different place in the future. “Validated” screeners can be useful and are worth paying attention to, but we should use our judgement.

This is an opinion and analysis article and the views of the author are not necessarily those of Scientific American.