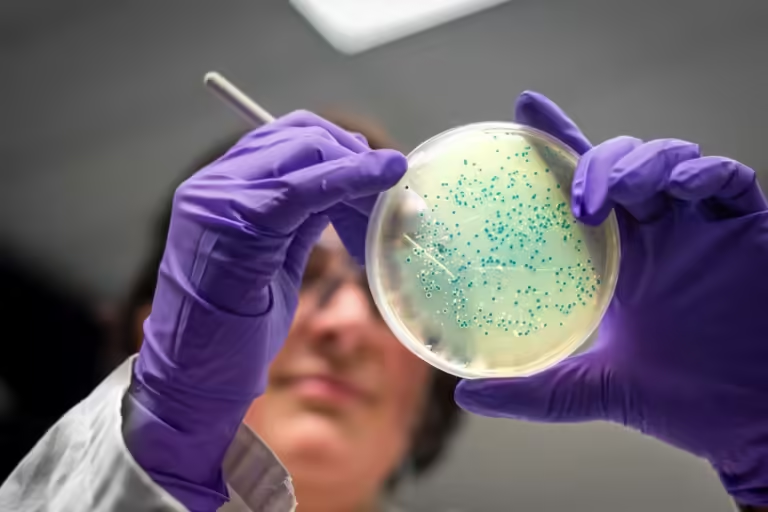

Some microbes are becoming more resistant to antibiotics

iStockPhotos

Global deaths directly caused by antibiotic-resistant infections are projected to rise from a record high of 1.27 million per year in 2019 to 1.91 million per year by 2050. Antibiotic resistance is expected to claim a total of 39 million lives between now and 2050, but more than a third of these deaths could be avoided if action is taken.

Resistance occurs when microbes evolve the ability to withstand drugs that were previously deadly to them, making them unable to cure infections. Widespread use of antibiotics in agriculture and medicine has led to the proliferation of resistant microbes and their spread around the world, but the full extent of the problem is unknown.

To address this issue, Eve Uhl of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) in Seattle and her colleagues set out to estimate the number of annual deaths due to antibiotic resistance from 1990 to 2021. “Our estimates are based on more than 500 million records,” Uhl says, “and we cover a wide geographic and temporal range.”

The team found that while deaths from antibiotic-resistant bacteria are increasing overall, the number of deaths among young children is falling due to vaccinations and improved medical care. Between 1990 and 2021, deaths from antibiotic-resistant bacteria fell by more than 50% in children under the age of five, but increased by more than 80% in adults over the age of 70.

Overall, the team concludes that the number of deaths attributable to antibiotic resistance increased from 1.06 million in 1990 to 1.27 million in 2019, before declining to 1.14 million in 2021. However, the declines in 2020 and 2021 are thought to be temporary, due to reductions in other types of infections as a result of COVID-19 measures, rather than due to permanent improvements in resistance measures.

In the study’s “most likely” scenario for the coming decades, deaths from antibiotic resistance would rise to 1.91 million per year by 2050. In a scenario in which new antibiotics are developed against the most problematic bacteria, 11 million deaths would be averted between now and mid-century. Even more deaths would be averted in a “better care” scenario in which more people have access to quality healthcare.

The 1.91 million annual deaths is much lower than an oft-cited figure of 10 million deaths by 2050 from a 2016 review. That projection was based on unreliable estimates, including the problem of non-antibiotic resistance in diseases like HIV and malaria, says Mohsen Naghavi, also a team member at IHME.

Marrike de Kracker of Geneva University Hospital in Switzerland says that while the new study is more thorough than previous studies, it still has some major limitations. For example, it assumes that the risk of death from antibiotic-resistant infections is the same around the world, which isn’t the case. “In areas with limited basic health infrastructure, drug-resistant infections don’t necessarily lead to more deaths than drug-susceptible infections,” de Kracker says.

She’s also skeptical of the team’s predictions. “I feel that predicting trends in antibiotic resistance is very unreliable,” de Kreker says. Drug-resistant bacteria can suddenly appear and disappear before experts really understand the underlying mechanisms, and unpredictable black swan events are common, she says.

topic:

Antibiotics