October 15, 2024

4 minimum read

Book review: How the author writes weave sweetgrass imagine a new economy

Robin Wall Kimmerer changed the way we think about sustainability. Could she do the same in economics?

Elva Etienne/Getty Images

nonfiction

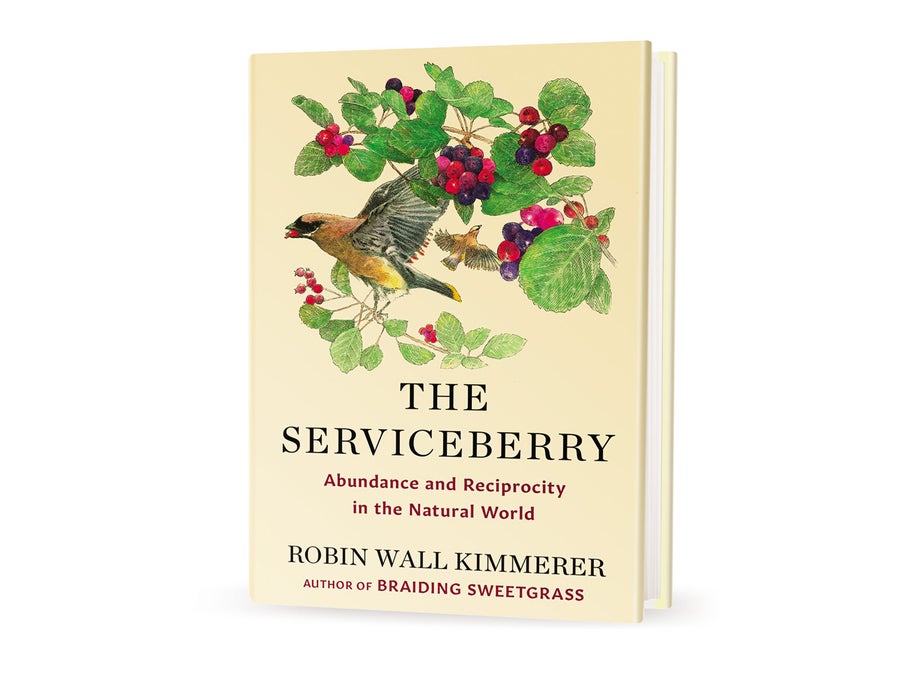

Serviceberry: Natural abundance and reciprocity

Written by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Scribner, 2024 ($20)

Nature gives us many gifts, but it’s easy to take them for granted. Not only the strawberries you buy at the supermarket, but also the plastic containers in which they are placed are made from ancient life forms that have turned into fossils and are now used as raw materials for plastic. How can we better value the natural world and build communities and economies that appreciate its richness?

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

this is the central question Serviceberry: Natural abundance and reciprocity. This is the third book by Robin Wall Kimmerer, an ecologist, professor at the State University of New York School of Environmental Science and Forestry, and member of the Potawatomi Nation. After seven sleepy years, her last book was How to Weave Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and Plant Teachingswas published in 2013 and quietly grew in popularity until finally new york times The 2020 bestseller list remains intact. Told through the personal lens of an indigenous scientist, Kimmerer’s concepts of bringing nature to life and respecting non-human species as if they were humans struck a chord that made me want to play. It was as if These ideas continue to resonate. She is regularly invited as a keynote speaker, her words are displayed on museum walls, and she received a prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” grant in 2022.

service berrywhich is derived from the 2022 essay. emergence magazineIt has a much slimmer volume. weave sweetgrass But they are written with the same lyrical, individual voice, inviting the reader into a world of possibilities. Comprised of short chapters separated by line drawings by illustrator John Burgoyne, this sweet work is based on her ideas about the gift economy and how indigenous wisdom influences it. She explores an ancient guideline known as the Honorable Harvest, an interpretation of the Gratitude Bullet Manifesto, and how the circular economy is a way to put these concepts into practice.

Kimmerer also continues to explore language and what it reveals about worldviews. In the opening chapters, you will learn: bozakumin Means “service berry” in Potawatomi. Serviceberry is a native shrub that produces blueberry-like fruit and is essential to the foodways of indigenous peoples. bozakumin Literally “the best berry,” the Potawatomi word “berry” also means “gift.” Languages around the world provide examples of the deep connection we once had with the earth that literally sustains us. The Greek word oikos is the root of both “ecology” and “economy,” writes Kimmerer.

Ah, but I forgot the link! In the opening scene, when Kimmerer fills a bucket with serviceberries and a flock of cedar waxwings join in the harvest, she sees the berries as “a pure gift from the earth.” I have never earned, paid, or worked for them. ” She invites readers to focus on the small bequests that abound. It reminds us that we live in a world of reciprocity, where donations are freed from artificial markets that create scarcity and individual desire. Things like a small free library on the front lawn and a free clothes box. And a neighbor invited me to come pick berries for free.

Kimmerer agrees that this generous way of living, close to both the land and neighbors, is most effective in small, close-knit communities. However, more than half of the world’s population now lives in urban environments, and the movement from countries to cities continues. Given this situation, how can we “reclaim ourselves as neighbors,” as she writes? What if service berries were a marketable commodity? , I can’t help but wonder if her neighbors would have opened up their farms to her for a day of free harvesting. I challenged her to do more to wrestle with the capitalist behemoths that almost all of us are caught up in, controlled by the machinations of people who are okay with destroying what others love in the name of profit. I wanted it.

“In an economic climate that demands more consumption, recognizing ‘enough’ is a fundamental act,” she writes. Awareness is a step. Transforming the economy is something else entirely. Kimmerer, who donated his book advance to land conservation and social justice causes, writes that he knows little about economics or finance. She seeks understanding through books and conversations, but like many of us, she seems to struggle with how such ideas are extended.

The answer, Kimmerler writes in his final and most powerful chapter, is to focus on ecological succession in nature. There, disturbances cause seemingly temporary changes in the system. Capitalism may not collapse, but it can seek conditions for economic inheritance into spaces where reciprocity is recognized. Not just by imagining a different way of being in the world, but by creating it. Many plants and animals go into a dormant state, waiting for the right moment to re-emerge and become fully alive. Like rhizomes that grow through the soil, can ideas and ways of being do the same?