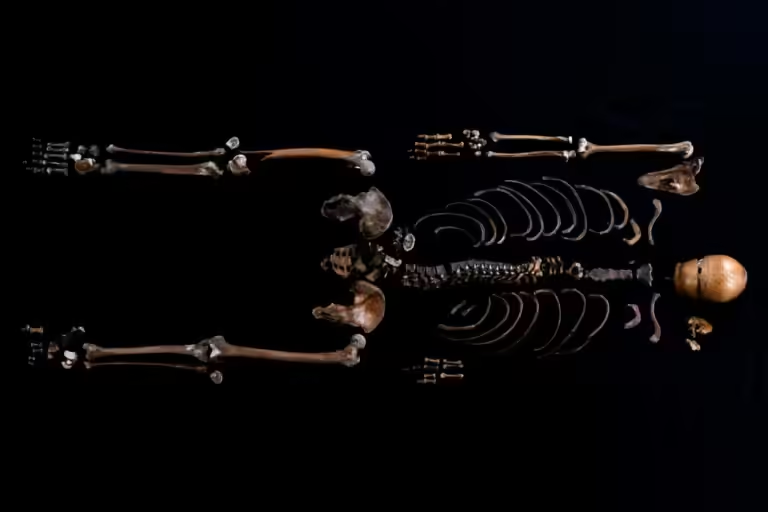

Complete skeletal remains of “Wellman”

Eiji Hojem, NTNU University Museum

Researchers now believe they have identified the remains of a Norwegian story written more than 800 years ago that depicts a dead man being thrown into a castle well.

The Sverris Saga is a 182-section Old Norse document that records the exploits of King Sverre Sigurdsson, who came to power in the late 12th century. In one section, it is said that rival clans who attacked Sveresborg Castle near Trondheim, Norway, “took the dead, threw them into a well, and buried them with stones.”

The well was located within the castle walls and was the only permanent source of water for the area. It has been speculated that the man thrown into the well in this story may have been suffering from a disease, and that throwing him into the well may have been an early act of biological warfare.

In 1938, part of a medieval well in the ruins of Sveresborg Castle was drained, and a skeleton was discovered beneath the rubble and rocks at the bottom. The skeleton, known as “Wellman,” was widely believed to be the remains of the person mentioned in the story, but it was impossible to confirm that at the time.

Now, using radiocarbon dating and DNA analysis of the remains’ teeth, Anna Petersen and colleagues at the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research in Oslo have found that the age range in which the man was alive is consistent with the castle attack. showed. Although it’s not conclusive proof that the man is the person mentioned in the story, “circumstantial evidence is consistent with this conclusion,” Pellersen said.

The Well Man’s skeleton was discovered in 1938

Riksantikvaren (Norwegian Directorate General for Cultural Heritage)

Additionally, the team was able to further enrich the story. “The investigation we conducted uncovered many details about both the incident and the person that were not mentioned in the story episode,” Petersen said.

For example, DNA suggests he likely had blue eyes and blonde or light brown hair. Researchers also believe, based on comparisons with modern and ancient Norwegian DNA, that his ancestors came from Vest Agder County, in what is now the southernmost tip of Norway.

What they couldn’t find was any evidence that the men were thrown into the well because they had a disease or to make their drinking water unusable, but no evidence to the contrary. can’t be found, and the question remains unanswered.

Michael Martin, from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, said the team’s approach of matching historical documents with DNA evidence was a great way to build family trees for long-deceased royal families and to “physically describe life stories.” It can also be applied to drawing schematically.” Bodies are recovered from archaeological excavations, as otherwise anonymous movements of people between geographical areas. ”

Researchers collected DNA from one of the skeleton’s teeth

Norwegian Institute of Cultural Heritage (NIKU)

“To my knowledge, this is the earliest instance in which genomic information has been recovered from a specific person, or even a specific person, described in an ancient text,” Martin said.

He says generating genomic information from ancient skeletons can provide new details about a person. “These details are not included in the original text, so genetic data enriches the story and provides a way to separate fact from fiction,” Martin says.

topic:

(Tag Translate)DNA