November 19, 2024

5 minimum read

Famous stars don’t form planets, and we don’t know why

Nearby star Vega featured in the 1997 film contact, For some unexplained reason, there appears to be a smooth disk without giant planets

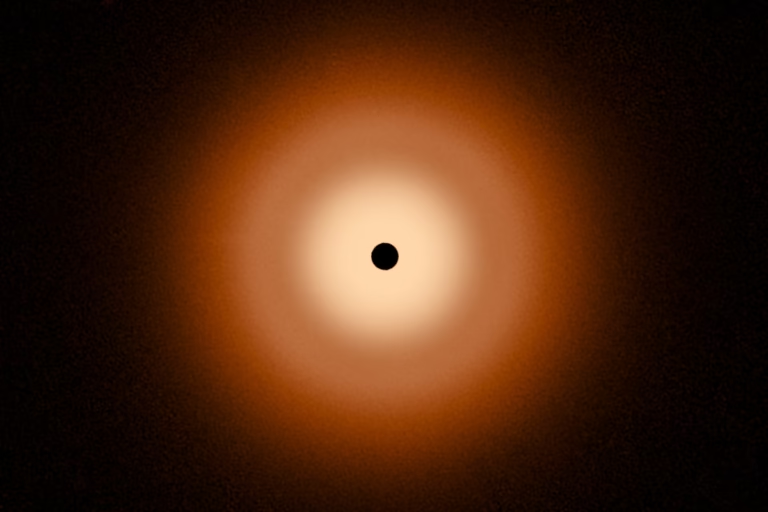

An image of the supernaturally smooth circumstellar disk around the nearby bright star Vega obtained using the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) on NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope.

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, S. Wolff (University of Arizona), K. Su (University of Arizona), A. Gáspár (University of Arizona)

The nearby star Vega occupies a special place in human culture. Just 25 light-years away, this glowing beacon has about twice the mass and 40 times the brightness of the Sun, and is so visible in Earth’s sky that it fascinated ancient astronomers around the world . It was also our planet’s North Star until a few thousand years ago, when Earth’s axis wobbled, Polaris took its place. (Vega will reclaim the North Star crown in 12,000 years). As such, many have considered this iconic star an interesting place to look for life, but astronomer Karl Karl, who imagined signals from an intelligent civilization coming from Vega in his 1985 novel, There was no one like Sagan. contactwhich was made into a blockbuster movie in 1997.

So when astronomers announced a puzzling discovery about the star earlier this month, there was some disappointment. Using the Hubble Space Telescope and its next generation, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), they made the most detailed observations of Vega yet and discovered something completely unexpected. The star does not appear to have formed any large worlds, even though it is about halfway through its billion-year lifespan. “We were really surprised,” said Kate Hsu of the University of Arizona’s Space Science Institute, who led the JWST observation. Instead, there is a very smooth disk of sand-like dust around the star, which may still harbor small planets, but does not form large worlds like Saturn or Jupiter. It seems so. “We were really hoping to see some giant planets,” says Hsu. The research was first published in two papers posted on the preprint server arXiv.org, and one later astronomy magazine, And the other thing is astrophysical journal.

Today, more than 5,500 planets known outside our solar system exist around stars ranging from faint stars known as red dwarfs to bright stars like Vega. “Nowadays we are used to finding planets around many stars,” says Anders Johansen, a planet formation expert at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. He was not involved in this study. When stars first form, they are surrounded by a debris disk, a swirling plate of dust and gas. During the early stages of a planetary system, these fragments coalesce to form planetesimals, the rocky building blocks of planets. Eventually, these will either suppress their growth and become small terrestrial worlds like Earth or Mars, or continue to grow and accumulate large amounts of gas and become giant planets like our exoplanets. Masu. The process is quick. “We expect most of the planet formation to be completed in about 10 million years,” said Skyler Wolff of the University of Arizona, who led the Hubble observations on Vega.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

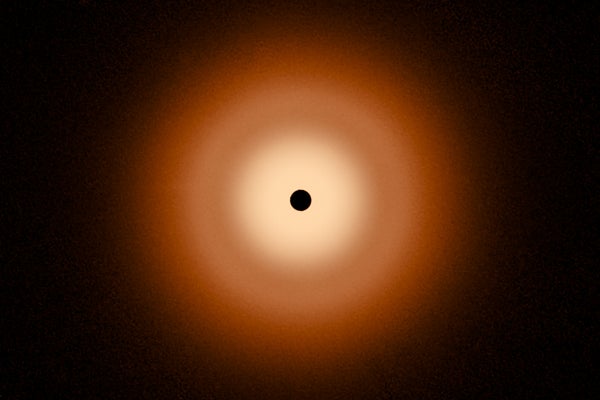

Vega is a 450 million year old A-type star. Previous studies, including NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope in 2005, have shown that astronomers have found that the star is surrounded by a large, bright disk of debris that stretches nearly 100 billion miles, a ratio comparable to that of Kuiper, which extends beyond Neptune. It was observed that the ratio was almost the same as that of the belt. But these latest observations were the first time they were able to study the disk in detail. “Right now we’re making comparisons to the asteroid belts of Mars and Jupiter,” Wolff said. The researchers expected to see giant planets carving gaps in this debris disk, similar to what is speculated to have happened in our solar system, but such gaps have never appeared. There wasn’t. The researchers rule out the existence of planets larger than Saturn that are more than 10 AU (10 times the distance between Earth and the Sun).

Vega’s circumstellar disk observed by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope using the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS). The disk’s smoothness suggests there are no large planets lurking inside.

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, S. Wolff (University of Arizona), K. Su (University of Arizona), A. Gáspár (University of Arizona)

The researchers say they can’t rule out the possibility of smaller planets, but the lack of giant worlds in the disk is troubling and suggests something unusual is going on there. This is an unknown obstacle in our understanding of planet formation. “We see a fairly smooth distribution of dust,” Wolff says, but around other A-type stars, such as Fomalhaut, observers have noticed a distinct structure formed by the presence of one or more planets. I discovered a disc that showed evidence of this. “The question then becomes, ‘What’s the difference?'” Wolff said. “Was there a chaotic event where a giant planet formed on one side (of the disk) and not on the other?”

Paul Karas, a debris disk expert at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the new study, suggests one possibility: The Vega system was formed by gas during early planet formation. is stripped away and a giant planet grows. “We don’t understand why planet formation is so unpredictable,” Karas says. “Here in Vega and Fomalhaut, we have two similar stars, but the results are very different. Scientists don’t like unpredictability. One has to follow the other. This shows that nature can surprise us.”

The lack of giant planets around Vega is not at all surprising to Bruce McIntosh, director of the University of California Observatory (UCO), who was not involved in the new study. Research has shown that up to 40 percent of the stars in the Milky Way galaxy have Jupiter-sized planets. “The fact that we have a disk with no large honking planets around it is not that surprising,” he says. “It’s a clear disk, reminiscent of freshly fallen snow.” Thanks to its brightness and proximity, Vega was the first star observed to have a disk about 40 years ago, and has become a touchstone in the study of debris disks. It is also interesting that . “Vega was the prototype, the first hint that there was dust around other stars,” McIntosh said. “Now we have a beautiful image. That’s kind of cool.”

Another possibility that no planets are observed around Vega is that Vega formed giant planets, but they were ejected from the system or moved closer to the star to a position where they are no longer visible. be. “There’s a lot of room right above the star to hide a planet,” McIntosh says. Johansen has a different suggestion. The idea is that a star’s metallicity (abundance of elements heavier than hydrogen or helium) may determine the existence of planets. “Vega is quite low in metallicity, with a third of the heavy elements found in the Sun,” he says. “Maybe there weren’t enough planetesimals to form planets.” It is thought to be particularly important in the formation of giant planets because it catalyzes the rapid growth of up to about 10 nuclei. “When you run the simulations, you don’t see much formation” around low-metallicity stars, Johansen says. “There isn’t enough time for the gas disk to grow before it disappears.”

Ideas like this may help us explore other worlds. You probably don’t want to focus too much on stars with low metallicity, assuming they don’t have many planets. Or maybe the opposite is true. “Perhaps the ‘habitability’ (of a planetary system) stops at high metallicity, because it produces too many giant planets,” says Johansen. Probably, “the less metallic a star is, the more likely it is that terrestrial planets exist.” Whatever the answer, it looks like we can rule out the possibility of a giant planet in Vega’s presence, but so far our telescopes aren’t powerful enough to probe any deeper. “We’re not ruling out the possibility of terrestrial planets, but someone else will have to make those observations,” Wolff said.