This year marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of human brain waves. The true story has been suppressed and lost to history, so few people know the story behind its amazing discovery. Almost 20 years ago, I visited the laboratories of pioneering scientists in Germany and Italy in search of answers.. What I learned overturned accepted history and exposed horrifying stories involving Nazism, brainwaves, war between Russia and Ukraine, and suicide. This history resonates with recent events, with Russia and Ukraine recently marking the grim milestone of 1,000 days into a conflict waged under the pretext of fighting the Nazis, which reflects how history, science, and society It reveals how the two are intricately intertwined.

Human brain waves, electrical vibrational waves that constantly pass through brain tissue, change depending on our thoughts and perceptions. Their value in medicine is immense. These reveal all kinds of neurological and psychological disorders to doctors and guide the hands of neurosurgeons in removing diseased brain tissue that causes seizures. Their newly recognized role in the healthy brain is changing our fundamental understanding of how the brain processes information. Like waves of any kind, radio waves passing through the brain create synchrony (think of water waves rocking a boat). In the case of brain waves, it is the activity between populations of neurons that is synchronized.

Who discovered brain waves? What did they think they discovered? Why was there no Nobel Prize?

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

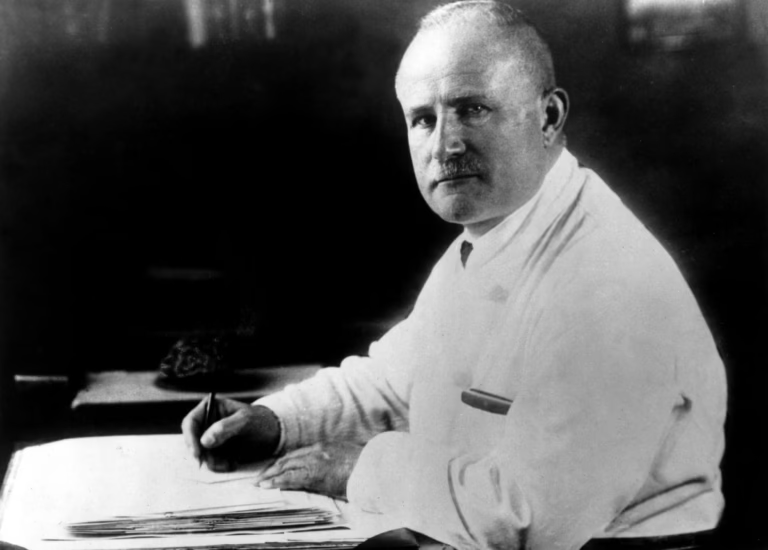

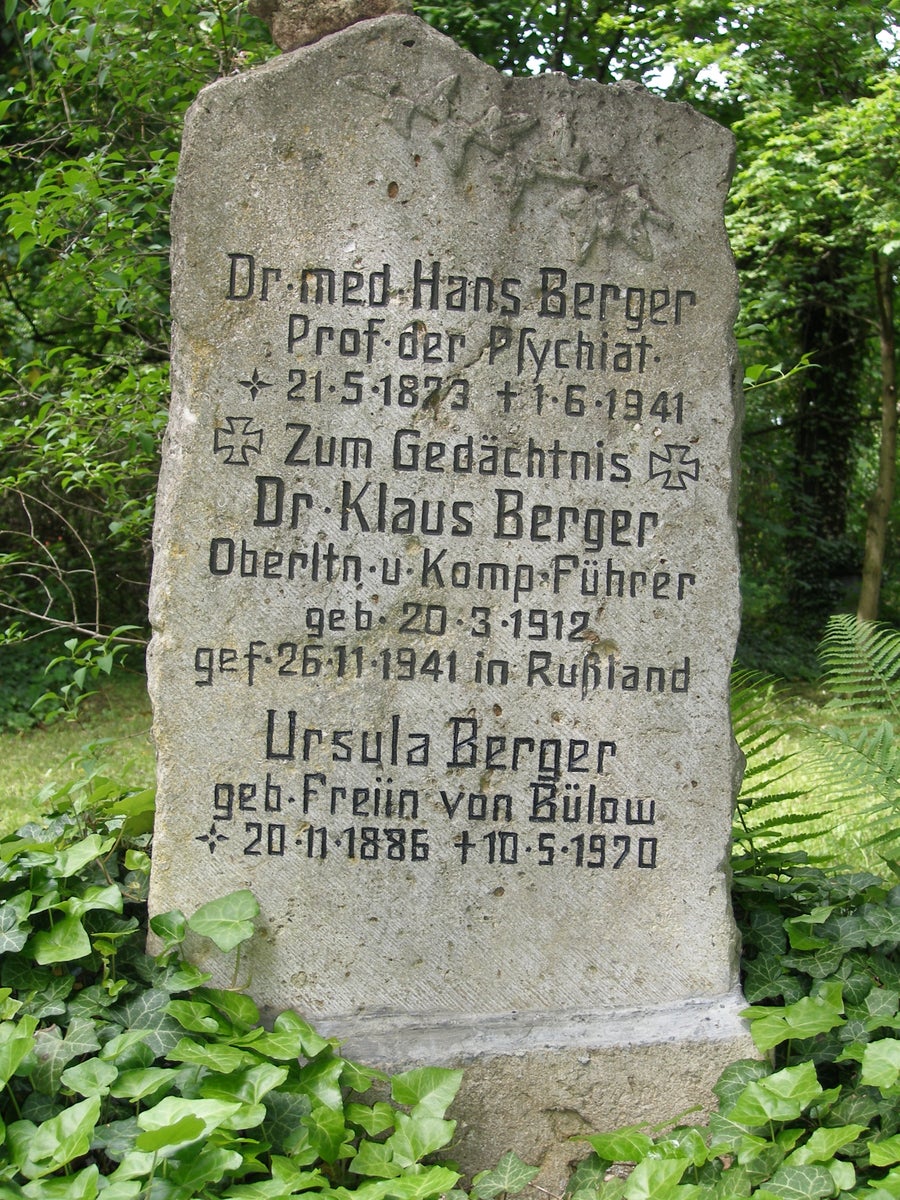

In the most common story, the reclusive physician Hans Berger recorded the first human brain waves in 1924 from a patient in a psychiatric hospital in the German city of Jena (late East Germany). He didn’t tell anyone what he was doing and kept his major discovery a secret for five years. With the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s, psychiatric hospitals became centers for forced sterilization and “euthanasia” to promote “racial hygiene.” Some of the methods developed in these facilities served as precursors to industrialized killing in concentration camps. As director of Jena’s psychiatric hospital, Berger would have been in the thick of it. At the time of my visit, the biography stated that Berger committed suicide in 1941 due to Nazi persecution.

“Since Berger was not a follower of Hitler, he had to abandon his work at the university. He was not expecting this and he was seriously injured…. (This) caused him to become depressed. which ultimately led to his death,” wrote psychiatrist Rudolf Lemke in a 1956 memorial. Lemke worked for Berger.

To me this seemed strange. Couldn’t the Nazis have fired Berger in the same way they purged 20 percent of Germany’s academics in 1933, ruthlessly expelling or “liquidating” disloyal politicians, administrators, etc.? ?

In Jena, I learned that Lemke was actually a member of the NSDP (Nazi Party). he worked at Elbgesund Heights Gericht (Genetic Health Courts) carry out forced sterilization of people who are broadly defined mentally and physically unfit, including the physically disabled, mentally ill, and alcoholics, among others. Like many other powerful figures, Lemke remained in Jena after the war, and his anti-Semitic and anti-homosexual views were hidden by the authorities. He was director of the psychiatric clinic in Jena from 1945 to 1948.

After World War II, Jena came under Soviet control, and documents revealing an extensive cover-up were lost or destroyed. When I visited Berger’s hospital, I met neuroscientist Christoph Redis and medical historian Suzanne Zimmermann, who had recently obtained Soviet records after the fall of the Berlin Wall. They revealed that Berger was actually a Nazi sympathizer. He killed himself in the hospital, she says, not because he was protesting, but because he was suffering from depression. Berger’s death, which took his own life, reflected the suicides of many people involved in Nazi atrocities at the time.

As Zimmerman leafed through a dusty lab notebook containing the earliest records of human brain waves, he pointed out a few anti-Semitic comments he had written beside it. Then she pulled out a stack of case files from the forced sterilization tribunals Berger served during the era when “eugenics” sought to exclude “unfits” from parent-child relationships. Hearing them read brought to mind the horrors that occurred when people petitioned courts not to sterilize themselves or their loved ones. Mr. Berger denied all appeals and sentenced everyone to forced sterilization.

The hospital in Jena, Germany, where Berger discovered brain waves.

Berger’s brainwave research was not well received. Berger, a believer in psychic telepathy, believed that brain waves could be the basis for psychic telepathy, but ultimately rejected the idea. Instead, he believed that brain waves were a type of mental energy. Like other forms of energy, waves of spiritual energy cannot be created or destroyed, but they can interact with physical phenomena. Based on this, he speculated that mental cognitive activity might cause changes in brain temperature. He explored this idea by inserting a rectal thermometer into the brains of psychiatric patients performing cognitive tasks during surgery.

Berger’s research was little known outside Germany until 1934, when Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist Edgar Adrian published his experiments in a prestigious journal. brain. Adrian acknowledged that so-called “burger waves” exist, but just as the brains of Nobel laureates change when they open and close their eyes, the eyes of water bugs change when they open and close. He implicitly mocked them. He did the same. Adrian did no further research on brain waves.

Berger is known for his discovery of human brain waves., However, research on animals predated his work. Nor did Berger invent the method he used to monitor brain activity. He applied techniques used in animal experiments by Adolf Beck in Lwów, Poland, in 1895, and by Angelo Mauser in Turin, Italy.

In contrast to Berger, Adolf Beck’s animal studies were aimed at understanding how the brain works when neurons communicate by electrical impulses. When his research was at its peak, his scientific work was interrupted by the Russian invasion. In 1914 Lviv was occupied by the invading Russians and renamed Lviv. Beck was captured and imprisoned in Kiev (now Kiev, Ukraine), then part of Russia.

While in prison, he wrote a letter to the famous Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov asking for help, and eventually Pavlov won Beck’s release.

Beck returned to his research in Lviv, and the next logical step was to look for human brain waves, but in World War II the German army invaded. They established a concentration camp in Lviv, where they exterminated the Jews. Beck, an intellectual and a Jew, became a target. When Beck was brought to a concentration camp in 1942, he swallowed cyanide and took his own life rather than let the Nazis take his life.

Remarkably, both pioneering brainwave scientists committed suicide from Nazism. One as a Nazi perpetrator and the other as a Nazi victim.

Berger’s tomb in Jena.

Neither Berger nor Beck knew, but they weren’t. The first person to record brain waves. The discovery was made by a London physician 50 years before Berger. This amazing discovery was buried in the obscurity of science because the idea was far ahead of its time, dating back to a time when the brain was shrouded in mystery and the world was gas-lit and powered by steam. It’s gone. Imagine how far neuroscience and medicine would be today if this scientific discovery, made in 1875, had not been lost to history for half a century.

The first person to discover brain waves was Richard Caton, a London physician. Caton presented his findings on brain waves recorded in rabbits and monkeys at the annual general meeting of the British Medical Association in Edinburgh in 1875. He accomplished this using a string galvanometer, a primitive device with a small mirror suspended on a string between magnets. When an electric current (in this case, from the brain) passes through the device, the string twists slightly, like a compass needle near a magnet. The oscillating currents detected in the brain were not measured in volts, but rather the deflection of light beams reflected by mirrors in millimeters. A published summary of his presentation “Current Currents in the Brain” shows that using this primitive device, doctors accurately estimated the most important aspects of brain waves. “In every brain examined so far, galvanometers have shown the presence of electrical currents…. Currents in the gray matter seem to be related to its function…”

Ironically, I traveled all over the world to study the discovery of brain waves, but the first researcher, Richard Caton, met George George in 1887 while visiting his family in Catonsville, Maryland. I learned that you published your research results at Town University. The town, where his relatives settled in 1787, is 30 miles from my home and next to the Baltimore-Washington Airport, from which I frequently depart to explore the world. But that fact, like his unappreciated brainwave research, has been lost to history. “Please read my paper on electrical currents in the brain,” he wrote in his diary. “It was well-received, but most of the audience didn’t understand it.”

This is an opinion and analysis article and the views expressed by the author are not necessarily those of the author. scientific american.