August 12, 2024

2 Time required to read

A regenerating deep-sea worm uses algae to split into three parts while still alive

Gutless, solar-powered earthworms genetically control the algae they grow

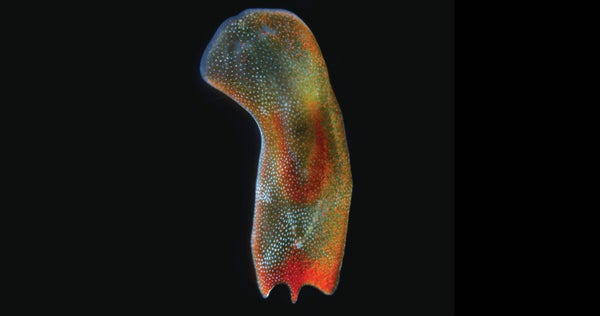

The green colour of this invertebrate comes from symbiotic algae.

At first glance, the tiny flatworms known as acoelomorphs appear to be very simple: they don’t even have a digestive tract, with just a few internal organs floating freely inside their bodies.

Some species of azoos host photosynthetic algae that provide them with energy in exchange for a safe home — a classic example of symbiosis. And these azoos do something amazing: when cut in half, they split into not two, but three new, thriving versions of themselves. First, a new tail sprouts from its head, then two hydra-like heads sprout from its tail, and then they split again into two separate organisms. Nature Communications The study suggests that these bugs manipulate the genetic activity of their symbiotic algae during their extreme act of regeneration. Scientists find this intriguing because many coral species also depend on symbiotic algae. Rising ocean temperatures today are forcing the algae to abandon their hosts, causing coral bleaching and sometimes the collapse of entire ecosystems.

Study co-author Bo Wang and his colleagues found that when they intentionally injured the acanthodes, the algae’s photosynthetic efficiency decreased as they began to regenerate. But at the same time, the algae’s photosynthetic genes became more active, potentially compensating for the deficiency. lanthanumThey likely made proteins that, when activated, prompt the algae to turn on these specific genes to aid in regeneration. “Here, the host cells are directly controlling the algal cells, presumably to the benefit of the host system,” says Wang, a developmental biologist at Stanford University. “That was the most surprising thing to us: that the photosynthetic pathway is controlled by the host’s regeneration program.”

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

“Most studies tend to look at symbiosis from the animal’s perspective because we’re more interested in the animals than the algae,” says Yixiang Chen, a developmental biologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Baltimore, who studies the algae-hosted corals. “The strength of this paper is that it focuses on the response of the symbiont algae and directly links that to the regeneration of the host.”

Knowing how hosts control their algal partners could help researchers manipulate the algae in corals to restore interactions lost due to stress, Wang says. He’s also interested in how algae that benefit invertebrates appear to in turn control their hosts, such as how the algae spread out normally light-shy insects like solar panels to expose the algae living on them to the sun.