September 17, 2024

4 Time required to read

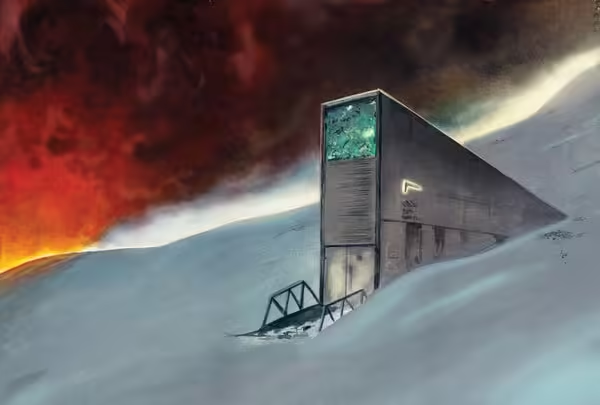

Arctic seed vault shows flaws in the logic of climate adaptation

The Svalbard seed vault’s difficulties show why we need to prevent, rather than plan for, climate disasters.

At 78 degrees north latitude lies the world’s northernmost city. It’s a strange place. Located high above the Arctic Circle and just 814 miles from the North Pole, in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, Longyearbyen has a population of just 2,400 but is home to more than 1.3 million seeds.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is an underground repository for storing seeds to “ensure that food crop varieties are not lost” in the event of a global crisis such as war, terrorism, or climate change. Billed as “an insurance policy to feed the world in 50 years,” the vault is located in a specific location and depth in the Arctic Circle to ensure that the seeds will not rot or germinate and will be available when needed. For added safety, the vault is refrigerated to 0 degrees Fahrenheit and designed to withstand a magnitude 10 earthquake. (By the way, the earthquake that caused the tsunami that devastated Fukushima, Japan, was a magnitude 9.) On the surface, the seed vault seems like a very solid idea. But its foundations are shaky.

The vault opened in 2008, following an earlier version that stored seeds in a nearby coal mine. It’s not a specific response to the threat of climate change, but it is exemplary of climate adaptation thinking. The logic behind it is this: climate change is on its way, and our political system seems incapable of taking meaningful action to stop it. Therefore, we have little choice but to prepare for a future facing severe climate disruption.

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

The biggest of these disruptions will be to food supplies, as severe droughts and heatwaves cause widespread seasonal crop failures and make important food species unable to grow in the places people are accustomed to. A diverse supply of seeds, including those adapted to hotter, more severe climates, may then be just what is needed to protect our food systems and stave off disaster.

While it’s good to be realistic about the climate future we face, the Seed Vault has a built-in hubris common to many adaptation plans: the idea that we know what we’re facing, so if we make a plan, things will work. But the vault’s weaknesses are already showing. In 2017, the vault was hit by a flood that was ironically caused by climate change. A very warm (but increasingly unexceptional) winter combined with heavy spring rains thawed some of the surrounding permafrost, flooding the entrance and threatening the safety of the seeds. Changes were made to the vault’s entrance to mitigate this particular risk, but this rupture, less than a decade after the vault opened, shows that we humans aren’t very good at predicting change, even in the short term.

Seed vault advocates have partly maintained the logic of their effort by brushing off the embarrassment of the flood: the vault’s timeline on the website of the vault’s partner, the Crop Trust, makes no mention of it. Guardian, “It was never in our plans for the permafrost not to be there and for us to have that kind of extreme weather,” said a representative for the Norwegian government, which owns and operates the vault. “The question is, is this just happening now or will it grow?”

You don’t have to be a climate scientist to know that Arctic permafrost is disappearing. The discrepancy is obvious even to the layman on Svalbard. And we’ve known for a while that the Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the planet. Princeton geophysicist Yoshiro Manabe predicted this effect, called polar amplification, in the 1970s (he was belatedly awarded a Nobel Prize in 2021 for this work). Currently, the Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the planet. Even if the whole world stopped burning fossil fuels right now, it would take decades or centuries for global temperatures to return to normal. Given the state of climate action (or lack of action), there’s no need to ask whether Arctic warming and permafrost loss will accelerate. It’s almost certain.

That’s not the only problem with the idea behind the seed vault. Proponents describe it as a “safety net against catastrophic famine,” but it’s doubtful it would work that way. A University of British Columbia scholar pointed out that seeds isolated from their environment don’t evolve, so if they are reintroduced decades later, they may face natural environments to which they are no longer adapted. This biological lag could render Svalbard’s zealously protected seeds useless, unable to grow or survive.

The vault’s focus on seeds also ignores vital food crops that are not normally propagated by seed, such as cassava. And if world famine really threatened, what were the chances that seeds could be collected, distributed, sowed and crops harvested in time to feed the world?

The problem of biological lag could be addressed by regularly updating the stored seeds with new samples from nature, but this is costly: even without such updating, the vault would cost €8.3 million to build, €20 million to upgrade and €1 million per year to maintain.—One wonders whether this is really a good use of conservation resources and scientific effort. And then there’s the carbon footprint: Keeping the basement at a frigid temperature of minus 0.4 degrees Fahrenheit requires electricity from Longyearbyen’s fossil-fuel-powered public power station.

It is wise to plan for the future. But the Seed Vault assumes that we know enough to plan effectively and that people will pay attention to our knowledge. History shows that this is often not the case.

The seed vault’s challenges are a reminder that the most important thing we can do now is not to plan for a climate disaster after it has happened, but to do all we can to prevent it while we have the chance.

This is an opinion and analysis article and the views of the author are not necessarily those of Scientific American.