Forecasters warned this spring that the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season will be especially dangerous due to a powerful combination of warming sea surface temperatures and the approach of a La Niña weather system that favors tropical storms. But as the season peaks in early September, the Atlantic basin has been eerily quiet. The recently named storm Ernesto dissipated around August 21. So were the dire hurricane forecasts wrong? Where did the storm go?

The short answer is no, and it’s complicated.

Despite the current lull, experts say this season has already been active and could become even more active. Five named storms have formed in the Atlantic so far this year: two tropical storms, two hurricanes and one major hurricane. Major hurricane Beryl reached Category 5 status faster than any other storm ever in the Atlantic. “We’re definitely in the beginning of a very active season,” said Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami.

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

Considering the number and strength of individual storms is only one way to assess the hurricane season. Another important tool for understanding tropical activity is a measurement called Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), which represents the overall activity of Atlantic tropical storms and hurricanes. To calculate ACE, scientists tally up the wind speeds of all storms strong enough to be named (maximum sustained winds of at least 39 miles per hour) every six hours. The wind speeds of each storm are squared and then the values are added together. This is done four times per day during the season.

This year’s ACE score is by no means tranquil, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reporting that it’s 50% higher than the seasonal average from 1991 to 2020. McNoldy said much of the strength so far this season is due to the powerful and long-lasting Hurricane Beryl, with Ernesto also contributing significantly to the current ACE score.

Plus, the Atlantic hurricane season runs until Nov. 30, so there’s plenty of time for activity to pick up again and wipe out the calm of recent weeks. “We’re puzzled about the last few weeks and probably this week, but it’s obviously too early to say anything about the hurricane season as a whole,” McNoldy said.

But the reality is that scientists are “stumped” by the current situation. McNoldy says the same factors that worried scientists ahead of this year’s hurricane season are still at play: Sea surface temperatures in the eastern Atlantic, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico all remain nearly 2 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) warmer than average, providing plenty of warm water for tropical storms to feed on. And as predicted, the El Niño weather pattern that tends to suppress hurricanes in the Atlantic is shifting toward La Niña conditions, which have lower wind shear rates that break up tropical storms.

So conditions are ripe for severe storms to form in the Atlantic, but they just don’t seem to be happening. The trend is far from being anything more than a hypothesis, but to understand the situation, scientists are turning to Africa, where the seed disturbances that turn into hurricanes are born. There, two phenomena could be influencing the current lull in hurricanes.

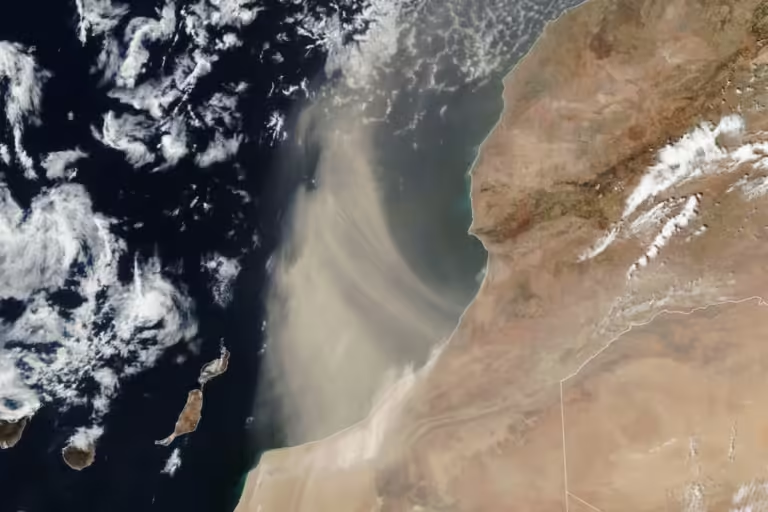

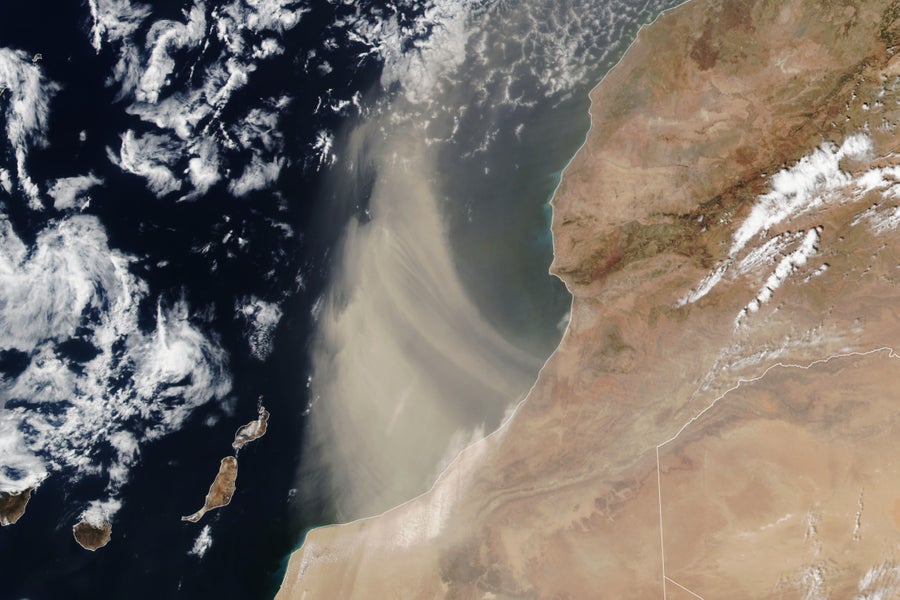

On August 24, 2024, a dense band of Saharan dust drifted offshore from southern Morocco across the Atlantic Ocean.

NASA Earth Observation satellite image by Lauren Dauphin using NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership VIIRS data.

One is columns of dust that rise up from the Sahara and are carried by winds across the Atlantic. It makes sense that this dust would affect hurricanes because it follows paths similar to those of tropical storms, and because the dust is dry and the storms feed on moisture. And while there’s been research showing interactions between Saharan dust and tropical storms, the relationship is very complicated, says Stanford atmospheric scientist and co-author of one such study published earlier this year.

While the study showed that Saharan dust could reduce hurricane precipitation, Wang thinks it may also reduce the occurrence of hurricanes in the first place. “I think it’s quite possible that dust is affecting this year’s drought hurricane season,” Wang says, but the explanation is still speculative. “I think we still need very rigorous scientific studies to do a causal analysis.”

A second intriguing factor is that this year’s West African monsoon has been unusually wet, says Kelly Nunez-Ocasio, an atmospheric scientist at Texas A&M University. The West African monsoon is a seasonal wind pattern that brings rain from the Atlantic Ocean to West Africa from June through September. Nunez-Ocasio has studied how the monsoon affects hurricane species, and in a paper published earlier this year, she and her colleagues modeled how the atmosphere responds to increased moisture.

These simulations show that in wetter conditions, the West African monsoon pushes a band of air called the African easterly jet northward. Under normal conditions, that jet drives atmospheric disturbances called African easterly waves that can become hurricanes when they reach the Atlantic Ocean. But a more northern location of the jet seems to prevent these waves from developing and persisting, making hurricanes less likely despite more moisture, Nunez-Ocasio and her colleagues found.

These conditions in Africa could continue to weaken this year’s Atlantic hurricane season, she says. “I don’t think we’re going to see a dramatic change in the climate that will suddenly produce multiple hurricanes by October,” Nunez-Ocasio says. “The situation is so stable that it’s hard to destabilize something that’s stable. It’s going to take a lot of time.”

Nunez-Ocasio called for forecasters to look beyond the Atlantic to assess conditions for hurricane formation, but she added that for the public, it’s important for people in the Caribbean and the southern and eastern U.S. to remain vigilant because even unnamed storms can cause severe flooding and other damage.

Forecasters agree: “We remain concerned about development risks across the Atlantic basin, as all it takes is one tropical storm or hurricane to cause devastation,” said Dan Harnos, a meteorologist at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

Forecasters also warn that despite the current lull in Atlantic activity, major storms are still possible this season. “Conditions still appear ripe for above-normal activity through the remainder of the hurricane season,” said Jamie Rome, deputy director of NOAA’s National Hurricane Center. Storms later in the season can be violent. For example, Hurricane Sandy formed in late October 2012, damaging parts of the Caribbean before heading down the U.S. East Coast, causing devastation in New Jersey and New York.

McNoldy emphasizes that it’s not unusual for hurricane activity levels to fluctuate. “We may see a few weeks of activity followed by a few weeks of quiet, and that’s pretty normal,” he says. He points to 2022 as an example, noting that there were no named storms in the Atlantic from July 2 to September 1 — two full months of eerily quiet weather. But in September, both Fiona and Ian became major hurricanes, the latter of which caused severe flooding along the Florida and North Carolina coasts.

“I think it’s too early to write off this season,” McNoldy said. “Even though we have this long period of calm, there’s still hurricane season ahead.”