December 5, 2024

5 minimum read

One more mutation would allow bird flu virus to bind more efficiently to human cells

A new study finds that tweaking a part of the H5N1 virus that infects dairy cows in one place could make it better able to attach to human cell receptors, making it more transmissible between humans. There are concerns that

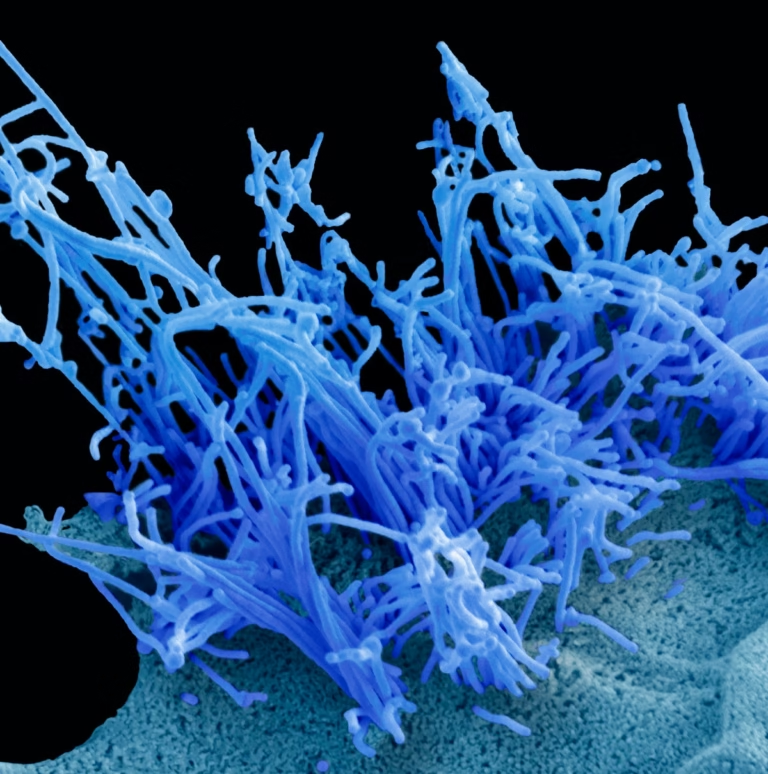

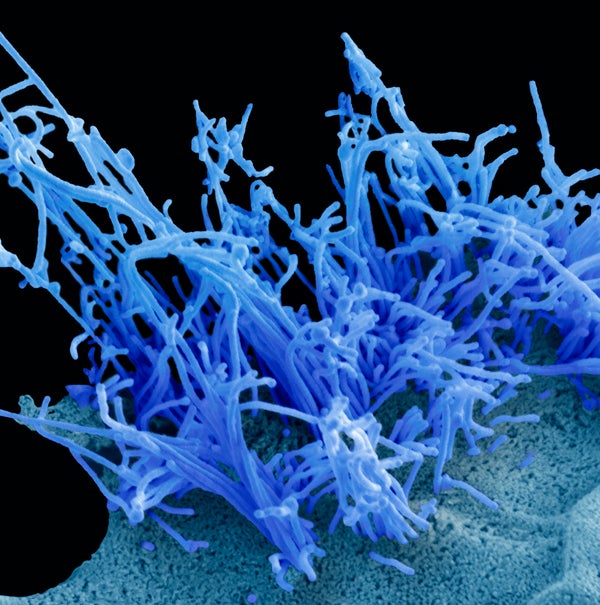

Human cells infected with avian influenza virus H5N1 (blue filament).

Steve Gschmeisner/Science Source

Scientists have discovered that H5N1, the highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza virus currently circulating in U.S. dairy cows, requires just one mutation to easily attach to human cells in the upper respiratory tract. discovered. The findings of this study were announced today. science, This points to a one-step pathway by which the virus could become more effective at infecting humans, and could have a major impact on new pandemics if such mutations spread widely in nature. There is a possibility of giving.

Avian influenza viruses are dotted with surface proteins that can bind to bird cell receptors, allowing the virus to enter cells. Bird cell receptors are different from human cell receptors, but the differences are “very subtle,” says study co-author James Paulson, a biochemist at Scripps Research. “We know that for the new pandemic H5N1 virus, we need to switch receptor specificity from avian to human. So what does that entail?” he and his co-authors were surprised. Best of all, the switch required only one genetic modification.

The specific group or clade of H5N1 responsible for the current outbreak was first detected in North America in 2021 and has been found in wild birds, bears, foxes, various marine mammals, and most recently, dairy cows. Since outbreaks of H5N1 infections began on U.S. dairy farms this spring, human cases have been primarily associated with sick poultry and cattle, and the majority of human infections are due to exposure risks. The incidence was mild, occurring among high-income farm workers (with some notable exceptions). There is no indication of human-to-human transmission, and the virus’s receptor binding preferences are a key barrier to it.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

“This is obviously speculative, but the more likely the virus is to bind to human receptors, the more likely it is to spread from person to person,” said Jenna Gassmiller, an immunologist at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. “There is a high possibility of infection, which is not a good thing.” , was not involved in the new study.

The study authors focused on changes in hemagglutinin, one of the surface proteins of H5N1. Hemagglutinin contains binding sites that allow the virus to attach to host cell receptors and initiate infection. Researchers generated viral proteins from the genetic sequence of a virus isolated from the first human case in Texas, which occurred in a person who developed bird flu after coming into contact with infected cattle. No live virus was used in the experiment. The scientists then introduced various mutations in hemagglutinin’s amino acid chain, the building block of the protein. A single mutation that replaced amino acid 226 in the sequence with another amino acid allowed H5N1 to switch its binding affinity from the receptor on bird cells to the receptor on human cells in the upper respiratory tract.

Past research has shown that some influenza variants, including the one tested in the new paper, are important for receptor binding in humans, Gassmiller says. Such genetic tweaks have been noted in previous influenza virus subtypes that caused pandemics in humans, such as in 1918 and 2009. But past viruses typically needed at least two mutations to successfully shift their preference for human receptors, co-author Ian Wilson explains. Structural and computational biologist at Scripps. “This was surprising; this single mutation was enough to switch receptor specificity,” he says.

Professor Paulson said the specific mutations the scientists tested in the new study were previously investigated during the H5N1 virus outbreak in poultry and some humans in 2010, but the It added that receptor binding was not affected. “But the virus is changing subtly,” Paulson said. “Now that mutation is causing change.”

Wilson and Paulson noted that the mutated H5N1 proteins in their study bound weakly to human receptors, but more strongly than the 2009 H1N1 virus that caused the “swine flu” pandemic. “What we are concerned about in causing a pandemic is the initial infection, and we believe that the weak binding seen with this single mutation is at least comparable to known human pandemic viruses. ” Paulson said. The study identified a second mutation in another region of hemagglutinin, at amino acid position 224, which, when combined with the mutation at position 226, may further enhance the virus’ ability to bind.

Professor Gassmiller said he was not surprised by the finding, given the known importance of the 226 mutation in influenza receptor preference, but added: “It is by no means surprising, given that only one mutation is actually required. Not,” he added. The study also “gives us an idea of what parts of the hemagglutinin protein to look for to understand what we should be looking for and what might change us for the better and potentially infect us.” ”

Recently, a Canadian teenager was hospitalized in critical condition due to avian influenza of unknown origin. Genetic sequencing shows H5N1 strains similar to those circulating in Canadian poultry, with mutations detected in two positions, one of which is the same position studied in the new paper226 It was. Scientists do not know whether any of the mutations are responsible for the boy’s severe symptoms, but they say they are concerned that the changes could indicate the virus could adapt to human cells. There are some people.

Paulson said it’s too early to draw conclusions or similarities between the teen’s case and the study’s findings. For example, he says, the amino acids the researchers tweaked in the study were not the same as those in the viral sequence in the Canadian case. “There’s a lot of talk of, ‘Oh my god, that amino acid has mutated,’ but there’s still no evidence that it actually provides the specificity needed to infect humans,” Paulson said. But the case remains important, he added.

Most human avian influenza cases reported this year were mild. In past outbreaks, H5N1 has caused severe respiratory illness because it prefers to bind to cells in the lower respiratory tract, Gassmiller said. “It’s basically causing a viral pneumonia. But when there’s increased binding to human receptors in the upper respiratory tract, as in this study, you’re more likely to get cold-like symptoms. However, the virus, which prefers the upper respiratory tract, including the nose and throat, is more likely to be spread by coughing and sneezing, which can then be spread further through human contact, he said.

Improved receptor binding does not in itself necessarily cause disease. Several other factors are also important, such as the ability of the virus to replicate and multiply in the body. However, it adheres to cells teeth That’s the first step, Paulson said. “The magic that we hope doesn’t happen is that all of this comes together to create the first (person-to-person) transmission and that becomes a pandemic virus,” he says.