November 21, 2024

5 minimum read

New outbreak of bird flu among young people raises concerns about virus mutations

Canada’s first human case of bird flu leaves a teenage boy in critical condition as human infections continue to occur in the western United States

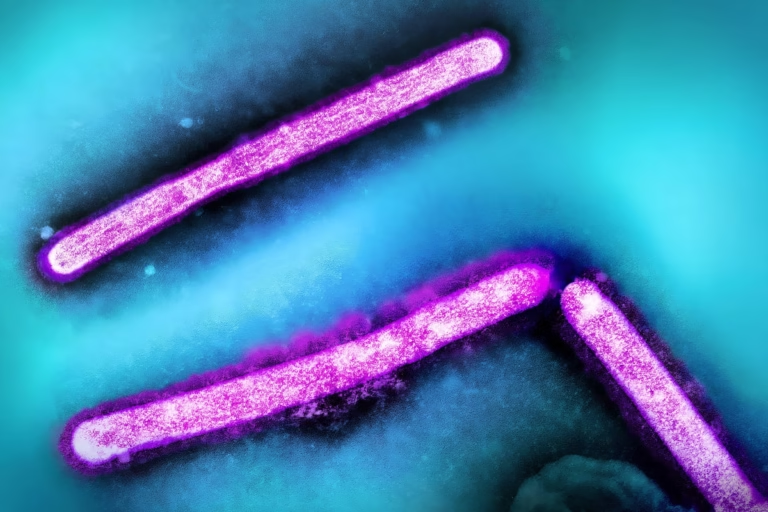

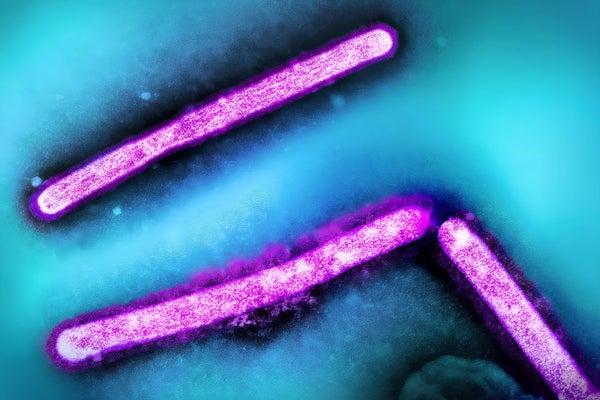

Three influenza A H5N1/avian influenza virus particles. The layout incorporates two CDC transmission electron micrographs that were rearranged and colored by NIAID.

Imago/NIH-NIAID/Image Point FR/BSIP/Alamy Stock Photo

Since the avian influenza strain was first detected in U.S. dairy cows this spring, it has caused relatively mild symptoms in humans, with most cases seen in farm workers who had direct contact with sick dairy cows and poultry. . But two unusual cases in children with no known previous contact with infected animals have led scientists to say the infection is a harbinger of a larger public health threat. Concerns are growing. On Tuesday, a child in California with a mild infection tested positive for low levels of the avian influenza virus, most likely the H5N1 strain. And Canadian health officials announced last week that a British Columbia teenager hospitalized with bird flu was in critical condition, the country’s first local infection.

“We haven’t been able to contain the outbreak,” said Seema Lakdawala, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Emory University School of Medicine. “This British Columbia case is probably not the only time a child has been hospitalized with H5N1.”

In both cases, family members and close contacts have tested negative for the virus, and authorities report there is no evidence of person-to-person transmission. The Canadian teenager, whose age and gender were not released, initially had symptoms similar to other previously reported cases: fever, cough, and an eye infection common in bird flu. He was suffering from conjunctivitis. However, the boy later developed acute respiratory distress, even though he had no underlying health problems. A Missouri man with a history of chronic respiratory illness tested positive for avian influenza in September while hospitalized for gastrointestinal symptoms.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recorded 52 cases of avian influenza since April 2024. But experts suspect this is likely an undercount. A recent CDC study of 115 dairy workers exposed to infected cows found that 7 percent had antibodies to H5N1, even though half of them reported no symptoms. It turned out that.

Although the study was conducted on a relatively small sample of farm workers, “what it highlights for us is that we are clearly underestimating the number of human cases,” Lakdawala said. he says. “Many infections that are probably asymptomatic or very mild do not always elicit a strong antibody response.” This could mean the study’s antibody tests may have missed some cases. There is a gender.

scientific american We spoke to influenza experts about recent cases of avian influenza in humans, preliminary genetic information, and risks of exposure and infection.

animal spill

The H5N1 virus currently circulating in North America was largely contained to wild and migratory birds until it began spreading to other animal populations, including mink, bears, foxes and marine mammals, starting around 2022. Currently in the United States, the virus primarily affects dairy cattle and poultry.

“I think what’s really changed since this particular strain emerged is its somewhat unique ability to infect across many different mammals,” said St. Jude Children’s Research in animals and birds. says Stacey Schultz Cherry, who studies the ecology of influenza. hospital. “There have been occasional reports of spills for quite some time, but nothing like what we’re seeing now.”

Although H5N1 is a highly lethal virus in poultry, cattle usually recover from symptoms such as fever, dehydration, and abnormal milk production. Lakdawala said the variety of animal species affected so far by the H5N1 virus poses problems in tracing the source of human infection.

Source tracking issues

Investigations are currently underway to determine the source of the infections in the California child and Canadian teenager. Neither reported any recent contact with sick wild animals, livestock or pets. Canadian health officials said at a press conference on Nov. 12 that it was “very likely” that investigators would not be able to confirm the source of the infection. For example, sick wild birds may not show any symptoms, Schultz-Cherry says.

Genetic sequencing of emerging strains has provided some clues. Test results for the strain that sickened the teenager suggest it is similar to the strain currently circulating in Canadian poultry. Some scientists have flagged certain mutations in the sequence that are known to be important for changing the virus’s receptor preferences, which could make it easier for the virus to bind to human cells. He pointed out that there is a gender. Dr. Lakdawala said genetic changes associated with the virus’ adaptation to mammals were seen in an analysis of another recent human case in Texas. “What this means is that the virus is adapting to humans to acquire mammalian genetic characteristics,” she suggests. “We need to stop the amount of H5N1 in animal species, especially cattle and poultry farms, to reduce the potential for human exposure and spillover. It prevents you from getting too many shots on goal.”

The risk of avian influenza remains relatively low for most people, but those who work directly with sick dairy cows or poultry are at increased risk. Although no sustained human-to-human transmission of H5N1 has been observed, Professor Schultz-Cherry is investigating whether there are any genetic changes that could allow the virus to acquire this ability or cause severe disease. He said it is important to monitor carefully.

Understanding severe infectious diseases

In past outbreaks, H5N1 has caused severe illness and, in some cases, death, Schulz-Cherry said. With the exception of the teen who was hospitalized, “We’ve been very fortunate that these events have been (mostly) mild, but it’s a little bit different than what we’ve seen historically and we don’t know why.” Canada health officials suggested the teenager’s critical condition may be an indication that the virus can be more severe in younger age groups. But experts’ ability to understand the risk of severe disease is further complicated by recent cases in young people, and by the fact that most human bird flu cases this year have not been made public.

Professor Lakdawala’s team investigated the role of pre-existing immunity – protection developed from past infections such as seasonal influenza – in the progression of H5N1 disease. The findings, which are currently under peer review, suggest that older people may have higher antibody cross-reactivity (the ability of antibodies originally primed for seasonal influenza to also react to H5N1) than younger people. . That may be because younger children have never encountered this type of influenza infection before, Lakdawala explains. “Our immune response is going to look at (the virus) differently based on prior immunity,” she says, but “what this (Canadian) individual’s prior immunity looks like? I don’t know,” he added. Schultz-Cherry and Lakdawala argue that it is too early to draw conclusions with such limited data and information.

There are several tactics that people and farmworkers, especially those at high risk of exposure, can take to lower their risk of infection. Washing hands, disinfecting surfaces such as milking equipment and farm equipment, and using protective equipment can help. In general, people should keep themselves and their pets away from dead wild birds and animals and avoid consuming raw milk and raw cheese. Getting the seasonal influenza vaccine is also especially important this year, Schultz-Cherry said. “We want to do everything we can to not give[the H5N1 virus]an opportunity to reassort” in people or animals infected with seasonal influenza, she said. “Could they actually share genetic material and potentially cause a new virus to emerge? I think that’s the biggest concern as we move into seasonal influenza season for humans.”