October 15, 2024

4 minimum read

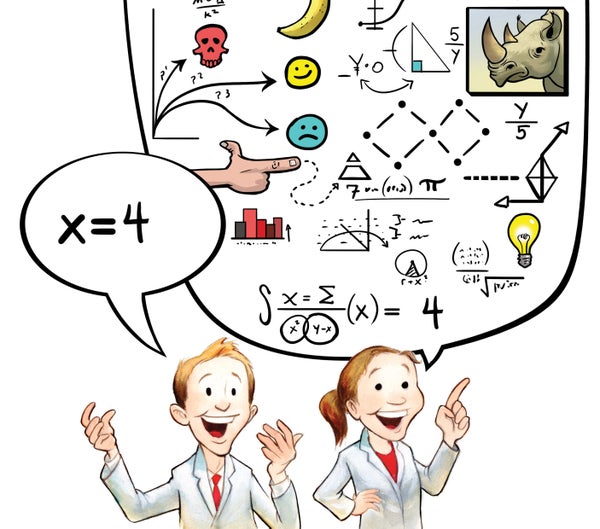

Contrary to Occam’s Razor, the simplest explanation is often not the best explanation

Occam’s Razor holds that the simplest explanation is closest to the truth. But the real world is very complex

If you’ve ever been around scientists, you’ve probably heard one of them say, “The best explanation is the simplest one” at some point. But is it? From the behavior of ants to the formation of tornadoes, the natural world is often extremely complex. Why should we assume that the simplest explanation is closest to the truth?

This idea is known as Occam’s (or Occam’s) razor. Also called the “principle of parsimony” or the “principle of economics.” And it has a family relationship with the “principle of least surprise,” which says that if an explanation is too surprising, it’s probably not correct. But real life is often messy and complicated, and as any good mystery novelist knows, sometimes the killer is someone you wouldn’t expect.

Let’s start with some evidence about the idea itself. The name comes from William of Ockham, a 14th century scholastic philosopher and theologian who formulated this principle in Latin. pluralitas non est ponenda sine necessitatewhich translates into English as “Entities should not proliferate more than necessary.” The point was an ontological discussion about substance that goes back at least to the time of Aristotle. “What exists in the world?” How can we know that they exist? This philosophical claim is a form of ontological minimalism. In other words, you shouldn’t call an entity unless you have proof that it exists. Even if we are certain that things such as comets exist, we should not invoke them as causal agents unless we have evidence that they cause the kinds of effects we are assigning. In other words, don’t make things up.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

In 1687, Isaac Newton expanded on this concept by The cause is—The Real Reason—When he wrote in his most famous work: Principia Mathematica, “We should admit no causes of things in nature unless they are true and sufficient to explain their appearance.” He continued: “To this end, philosophers say that nature does nothing in vain, and that more is vain when less is useful. because he prefers simplicity and does not affect the extravagance of the cause.”

Newton was one of the greatest scientists of all time, but this claim is strange if you stop and think about it. Who can say what “pleases nature”? And doesn’t this guidance assume that we actually know what we’re trying to understand?

Consider the work of astronomer Vera C. Rubin, who discovered convincing evidence for the existence of dark matter. While studying the motion of spiral galaxies, Rubin found that the speed at which stars rotate around the center of the galaxy was such that these galaxies contained additional mass about 10 times heavier than the visible stars. I discovered that it only makes sense if The claim of a new form of “dark” matter (invisible, invisible, and present in much greater quantities than the visible matter in the universe) was not a simple explanation, but it is the best explanation. It turns out.

Physics is full of surprising, unexpected, and difficult to understand explanations. Newton described light as being made of particles, but other scientists of his time described light as waves. However, quantum mechanics tells us that light is both a wave and a particle in some respects. Newton’s explanation was simpler, but modern physics has found that more complex models are closer to the truth.

Things get even more complicated when we look at biology. Imagine two smokers who both smoked a pack a day for 30 years. Some people get cancer. The other one is not. What is the simplest explanation? For decades, the tobacco industry’s answer has been that smoking does not cause cancer. Simple but wrong. The correct answer is that the disease is complex and all the factors involved in carcinogenesis are not yet understood.

And then there’s the vexed question of how to define simplicity. Consider the ongoing debate over the origins of the coronavirus pandemic. Some critics have invoked Occam’s razor on the side of the lab leak theory, which suggests that the SARS-CoV-2 virus did not jump from wild animals to humans, but instead leaked from a facility. However, it is not clear whether this theory is correct simpler. You could also argue the opposite. Given that most past pandemics were zoonotic in origin, a simpler explanation is that this pandemic was no different.

Occam’s Razor is neither a fact nor a theory. This is a metaphysical principle, an idea that holds independently of empirical evidence. (Think “God is love” or “Beauty is truth.”) But unless you are prepared to make assumptions about God and nature, there are legitimate reasons to prefer simple explanations to complex ones. There’s no reason. Additionally, things can often get complicated in HR. Human motives are usually multiple. People can be good or bad, selfish or selfless, depending on the situation. Ethicists’ bookshelves are lined with books that examine why good people do bad things, but the answers are rarely short and sweet.

In 1927, British geneticist JBS Holden wrote in his essay “Possible Worlds” that “the universe is not only stranger than we imagine, but stranger than we are.” can Assume. “In fact, new things exist in the world, and rare events may be rare precisely because various events are intricately intertwined. If you think about it this way, Occam’s razor is just a matter of imagination. It turns out to be a failure.

Our explanations must match the world as closely as possible. Science means letting the chips go, and sometimes it means accepting that the truth is not simple, even if it makes our lives easier.

This is an opinion and analysis article and the views expressed by the author are not necessarily those of the author. scientific american.