As the H5N1 avian influenza virus continues to rampage through U.S. dairy herds, it is also infecting human farm workers. Another strain has infected poultry farm workers and recently occurred in Washington state. The U.S. Department of Agriculture announced Wednesday that the virus was first detected in pigs at a farm in Oregon. Now, as the annual seasonal flu season approaches, some health experts are concerned that bird flu could spread dangerously.

At least 39 human H5N1 infections have occurred in the United States this year. California had 15, Colorado had 10, Washington had nine, Michigan had two, Texas had one, and Missouri had one. (A second person in Missouri was also likely infected, but their blood test results did not meet the official definition of a “case.”) Officials also said the possibility of human-to-human transmission in Missouri Most of the known cases are infected. It is mild and is characterized by mild eye infections and respiratory symptoms.

Apart from the Missouri case, all of these people had known contact with infected livestock. All nine cases in Washington state and nine cases in Colorado involved farm workers who killed infected chickens. The remaining cases were dairy farm workers. A total of 395 herds in 14 states have tested positive for H5N1.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

With the number of infections rising steadily in both livestock and humans, some experts are concerned about the risk of a more widespread outbreak of the virus, which has the potential to cause a pandemic. Influenza viruses have several characteristics that make them suitable for this. For one, it constantly mutates in a process known as genetic drift, necessitating a new flu shot every year. If there are enough mutations of the right kind, the virus can make a quantum leap known as a genetic shift and cause a pandemic.

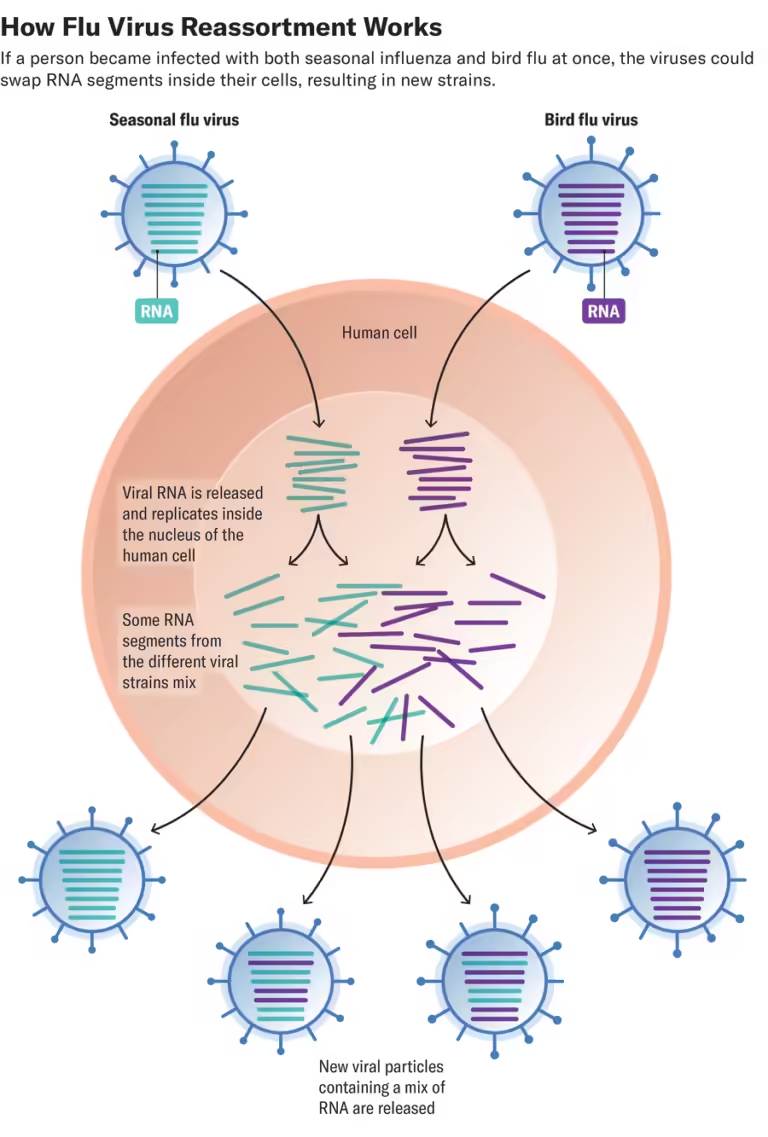

Another tool in the influenza virus kit is something known as reassortment. The genetic material of the influenza virus consists of eight RNA segments. When multiple viruses infect and replicate in the same cell, these segments are exchanged, producing one of 256 possible combinations. This reassortment can create a virus that contains features of both parent viruses, potentially making it more infectious and virulent. This process is thought to have produced the 2009 H1N1 swine flu from a mixture of US and European swine flu virus strains, causing a (thankfully mild) pandemic.

If a person were infected with both the H5N1 avian influenza virus and seasonal influenza, could such a reassortment occur, resulting in an H5N1 strain that is more infectious to humans? It’s possible, experts say. But Richard Webby, an infectious disease researcher at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, said reassortment alone would not create a virus that could cause a human pandemic. It may be necessary to wake him up.

“To get from where we are now to a pandemic virus, reassortment alone is not going to get us there, at least in my opinion,” said Webby, director of the World Health Organization’s Collaborative Research Center on Influenza Ecology. . with animals and birds. “Reassortment would be required, and then some significant mutations would occur in (certain) genes.” So far, the key mutations needed for the virus to spread efficiently among humans are: has not been detected in any of the human cases whose genes have been sequenced.

If H5N1 develops these mutations, reassortment could move the virus from infected humans’ eyes (the most common site of infection in farm workers) to the respiratory tract, Webby says. . If it were to occur, he says, such admixture would most likely occur in the human host. Although cows can be infected with human influenza viruses, those viruses are unlikely to replicate in the cow’s udder, where H5N1 appears to replicate best.

Historically, pigs have been considered ideal mixing vessels for pandemic pathogens because they are susceptible to both human and avian influenza. Amy Baker, a research veterinary medical officer at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said human seasonal viruses are spilled into pigs fairly regularly. Baker et al. showed that the 2.3.4.4b strain of H5N1, currently prevalent in wild birds and dairy cattle, can also replicate in pigs.

The pig that tested positive for H5N1 in Oregon was kept on a backyard farm with poultry and other animals. It is not yet clear whether the pigs transmitted the virus to other animals, but health authorities are investigating. All five pigs on the farm were euthanized. Because the farm is a non-commercial operation, there are no concerns about the domestic pork supply, USDA officials said in a recent statement.

“This seems to be a fairly limited occurrence on a backyard farm, so I don’t think it poses a particular risk in and of itself, assuming there was no movement of animals to other farms,” Webby said. say. But if this represents an actual infection in the pigs, rather than just a positive nasal swab, “it suggests that pigs are naturally susceptible to the virus,” he says.

If H5N1 begins to infect pigs on commercial farms, reinfection with seasonal influenza would increase. “We know that reassortment happens frequently in pigs. There are viruses in pigs that are very closely related to humans. So it definitely, definitely increases the risk. I guess.”

Baker said there are still many unanswered questions about how the H5N1 virus got into cattle and started spreading in the first place. She agrees with Webby that there is little risk of the virus reassembling with human seasonal influenza viruses in cattle, as there is no evidence that the latter pathogen can be transmitted to animals. However, she says there is “always a chance” that a more dangerous hybrid virus could be created if pigs or people were infected with both viruses at the same time.

This risk is why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is urging farmworkers to get vaccinated against seasonal influenza. The United States has stockpiled H5N1 vaccines but has not yet distributed them. There are also concerns that low confidence in vaccines could affect vaccination. It remains unclear what the standards of various authorities are for distributing H5N1 vaccines to farmworkers and other susceptible populations, but evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission is a strong factor. Very likely.

“This is not a hard-and-fast rule,” said Nirav Shah, chief deputy director of the CDC. scientific american At last week’s press conference. “There are a wide variety of factors to consider when evaluating the benefits and drawbacks of vaccination.” These factors include the emergence of person-to-person transmission and increased virulence and disease severity. However, none of these factors have yet been confirmed, he added. In the meantime, H5N1 patients and their close contacts are being treated with the drug oseltamivir (Tamiflu).

Some scientists are calling for cattle to be vaccinated with H5N1 vaccines, and the USDA Center for Veterinary Biologics has approved field safety testing of some vaccines. “I think there is an opportunity to use the H5 vaccine in cattle because it is the only subtype that we currently have knowledge of infecting cattle,” Baker said. “And I think if we can reduce the amount of virus that is shed through milk, not only will it protect farm workers and the public, but it will also benefit the milk producers.”

At this point, it’s unlikely that farmworkers could be infected with H5N1 at the same time as seasonal influenza, Webby said. However, if the influenza epidemic becomes serious this winter, the risk may increase. Hundreds of people have been infected with bird flu over the past quarter century, but bird flu has not yet begun to spread widely among us. This fact “suggests that this virus has a high hurdle to overcome in order to become a human virus,” Webby said. But anything that increases the likelihood of transmission is clearly a concern, whether it just leads to more transmission from livestock to humans, or whether it could reassemble with seasonal viruses in humans. All of that will increase the risk. ”