The following essay is ![]() The Conversation is an online publication covering the latest research.

The Conversation is an online publication covering the latest research.

The Nutrition Facts label, the black-and-white information box that has appeared on nearly every packaged food in the United States since 1994, has recently become a symbol of consumer transparency.

From Apple’s “Privacy Nutrition Label,” which makes public how smartphone apps handle user data, to “Clothing Labeling” labels that standardize ethical disclosures on clothing, policy advocates across industries hold up “nutrition labeling” as a model for empowering consumers and achieving socially responsible markets. They argue that an intuitive information fix can solve a range of market-driven social ills.

Support science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

But this familiar, everyday product label actually has a complicated history.

I study food regulation and food culture, and became interested in the Nutrition Facts label while studying the history of Food and Drug Administration policies on food standards and labeling. In 1990, Congress passed the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, requiring nutritional labeling on all packaged foods to address growing concerns about rising rates of chronic disease associated with unhealthy diets. The FDA introduced the “Nutrition Facts” panel in 1993 as a public health tool to help consumers make healthier choices.

The most obvious purpose of the Nutrition Facts label is to inform consumers of the nutritional properties of their foods. But in reality, the label has done more than just inform shoppers. It also represents a variety of political and technical compromises about how to translate foods into nutrients that meet the diverse needs of the American public.

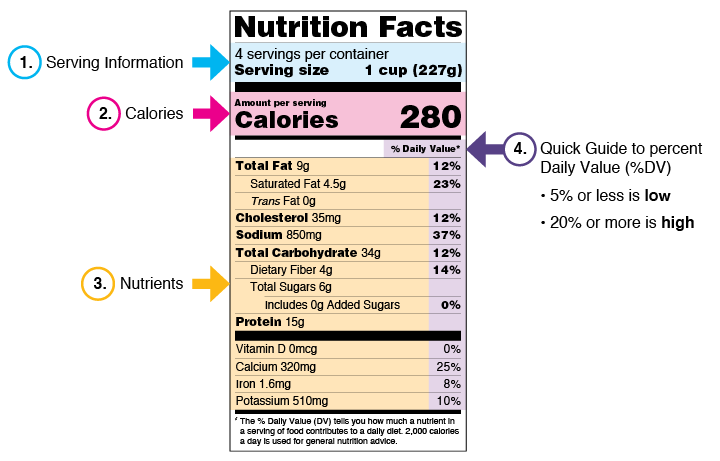

Where does the “% Daily Value” come from?

The percentage Daily Values (DV) listed on labels are not all derived from the same sources, reflecting different public health goals for the labels.

Recommended values for vitamins and other micronutrients are based on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Recommended Dietary Intakes (RDA). Vitamin RDAs were developed out of historical concerns about nutrient deficiencies and meeting minimum requirements.

The percentage daily values for macronutrients (carbohydrates, fats, and protein) are based on the USDA Dietary Guidelines. The daily values for macronutrients have been updated due to new concerns about overeating and an emphasis on “negative nutrients” that recommend maximum intake levels.

DVs reflect two fundamentally different concerns: Micronutrient values represent floors — the basic, minimum vitamin requirement that children should meet to avoid malnutrition — while macronutrient values represent ceilings — maximum limits that adults should aim to avoid if they want to prevent future health problems from excessive intake of high-sodium or high-fat foods.

The current Nutrition Facts label is divided into four main sections.

Food and Drug Administration

Why 2,000 calories?

The FDA almost used 2,350 calories as the standard for calculating daily intake because that was the population-adjusted average calorie requirement recommended for Americans over the age of 4. But after opposition from health groups who worried that a higher standard would encourage overconsumption, the FDA settled on 2,000 calories.

FDA officials felt that this number was “less likely to be misinterpreted as an individualized goal because round numbers are less implicitly specific.” That means that for most American consumers who read the label, 2,000 calories is not an actual goal. Rather, it is an example of public health concern for population risk, which one scientist called “treating sick populations, not sick individuals.”

By choosing a round number that was easy to calculate and a number of calories lower than the average American’s intake, FDA officials prioritized practicality and usefulness over precision and objectivity. They believed that recommending a low standard of 2,000 calories would offset Americans’ tendency to overeat and do more good than harm to the population as a whole.

Who decides what the serving size is?

According to the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, serving sizes should reflect the “amount typically used.”

In practice, there are regular negotiations between the FDA, the USDA (which also sets serving sizes for dietary guidance tools like MyPlate), and food manufacturers. Each agency conducts research into consumer expectations and food consumption data, taking into account how foods are prepared and “typically eaten.”

Serving size is also determined by the product’s packaging – for example, a soda can is generally considered a single serving container and therefore counts as one serving regardless of the amount inside.

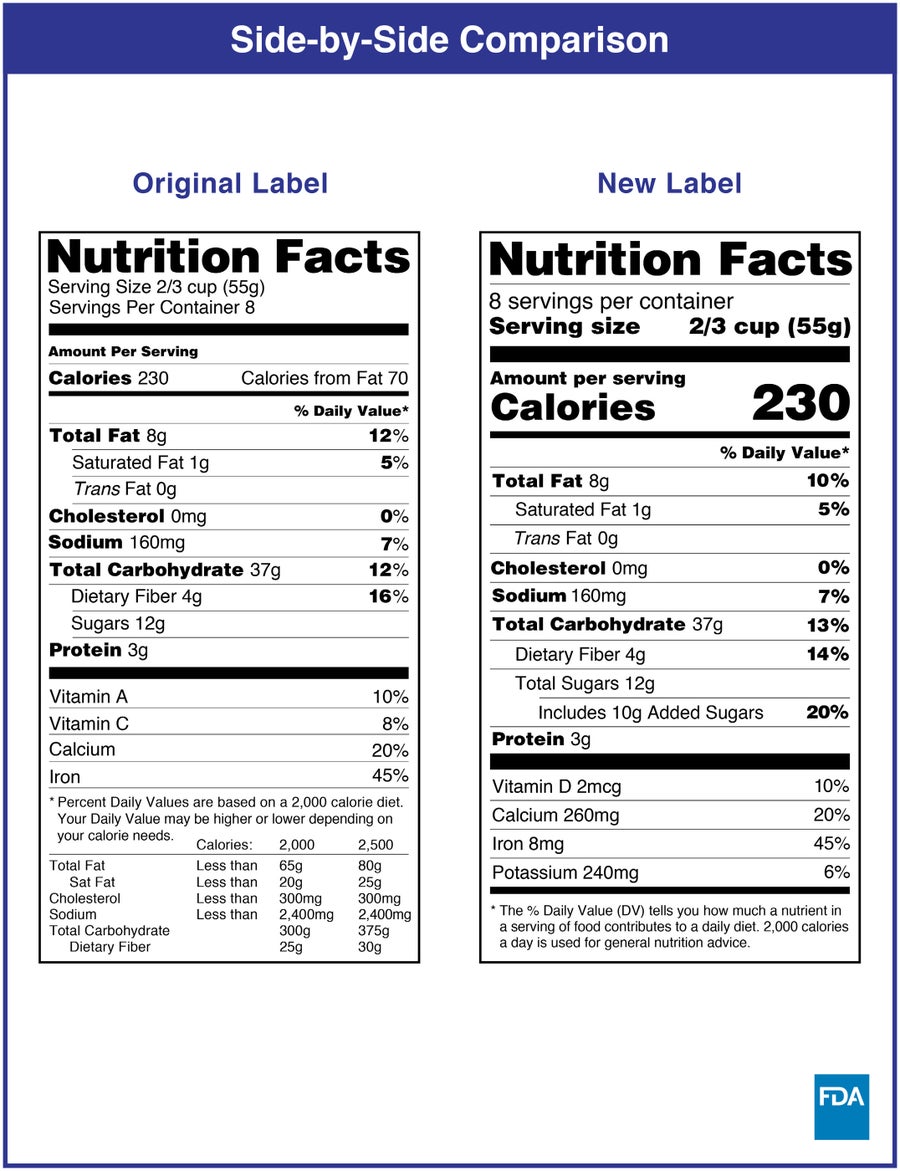

Compare the 1993 Nutrition Facts label to the 2016 design.

Food and Drug Administration

What’s in a name?

The label was originally called “nutrition values” or “nutrition guide” to emphasize that the daily values were recommended. Then FDA Deputy Commissioner Mike Taylor proposed “Nutrition Facts” to give the impression of being legally neutral and scientifically objective.

The new design—subdued black Helvetica text on a white background, with indented subgroups and thin lines for easier readability—and the authoritative, bold title established the Nutrition Facts label as an easily recognizable government brand.

This has led to imitators emerging in other policy areas: first “Drug Information” for over-the-counter drugs, then various tech industry consumer protection initiatives such as the Federal Communications Commission’s “Broadband Information” and “AI Nutrition Information.”

The Nutrition Facts panel has remained largely consistent since the 1990s, despite some updates, including the addition of a line for trans fats in 2002 and added sugars in 2016, to reflect changing public health priorities.

A new way to calculate the facts

Establishing the Nutrition Facts label required building an entirely new technological foundation for nutrition information. Translating the diverse American diet into consistent, standardized nutritional information required new measures, testing procedures, and standard references.

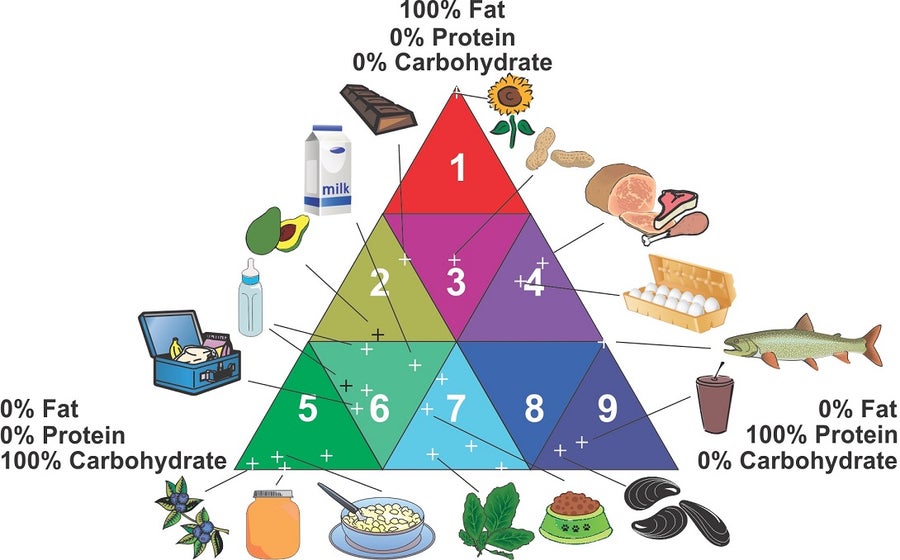

A chart comparing different foods based on their fat, protein, and carbohydrate content.

National Institute of Standards and Technology

A key player in developing this technological infrastructure was the Association of Certified Analytical Chemists. In the early 1990s, an AOAC task force developed the Food Triangle Matrix, which classifies foods based on their percentages of carbohydrate, fat, and protein. The objective was to determine the appropriate way to measure nutritional characteristics such as calories and sugar content, since the physical properties of a food affect the validity of each test.

The Legacy of Nutrition Facts Labels

Now, public-private collaborations are making further progress in converting foods to simplified nutrient profiles, making Nutrition Facts labels plug-and-play. USDA FoodData Central provides a comprehensive database of individual ingredient nutrient profiles that manufacturers use to calculate Nutrition Facts labels for new packaged foods. This database is also used by many diet and nutrition apps.

The analytical tools developed for nutrition labels helped lay the basic information foundation for today’s digital diet platforms, but critics argue that these databases reinforce an overly reductionist view of food as simply the sum of its nutrients, ignoring how different forms of food, such as water content, fiber content, and porous structure, affect how nutrients are metabolized in the body.

Indeed, many nutrition researchers concerned about the negative health effects of ultra-processed foods talk about food matrices to emphasize the exact opposite of what AOAC pursued with the food triangle: the need for a holistic understanding of the health effects of foods.

Surprisingly, the Nutrition Facts label’s greatest impact may be that it has inspired the food industry to reformulate products to achieve attractive nutritional profiles, even when consumers don’t read the label carefully. Although the Nutrition Facts label was conceived as an educational tool, I believe it has actually acted like a market infrastructure, reshaping the food supply to align with changing dietary trends and public health goals long before consumers ever found those foods in the supermarket.

This article was originally published on conversation. read Original Article.