The following essay is ![]() The Conversation is an online publication covering the latest research.

The Conversation is an online publication covering the latest research.

With the extremely hot summer continuing in many parts of the country and high school sports teams soon to begin practice, now is the time for athletes to slowly and safely begin to build strength and stamina before taking to the field.

Research has shown that the risk of heatstroke is highest during the first two weeks of team practice, when players’ bodies are still acclimating to the exercise and heat. Being physically prepared for increasingly intense team practices can help reduce the risk.

Support science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

I’m an athletic trainer who specializes in critical injuries and heat illness, and here’s what everyone needs to know to keep athletes safe in the heat.

Why do athletes need to slowly return to training?

One of the biggest risk factors for developing dangerous exercise-related heatstroke is your fitness level, as it affects your heart rate, breathing and your ability to regulate your body temperature.

If an athlete waits until the first day of practice to begin exercising, the heart will not be as efficient at pumping blood and oxygen through the body, and the body will be less able to dissipate heat. As the amount of exercise increases, changes occur in the body that improve thermoregulation.

That’s why it’s important that athletes gradually and safely increase their activity for at least three weeks before team practices begin.

There are no hard and fast rules on how much exercise is appropriate for preparation; it varies from person to person and sport to sport.

It’s important not to push yourself too hard: it takes time to get used to exercising in the heat, so start slowly and pay attention to how your body responds.

How hot is too hot to exercise outdoors?

Any hotter than normal day carries risks, but conditions vary across the country. What’s hot in Maine can be cool in Alabama.

If the temperature outside is much higher than usual, you are more likely to suffer from heatstroke.

To be safe, avoid exercising outdoors during the hottest hours. Exercise in the shade or in the early morning or evening when the sun’s rays are not as hot. Wear loose-fitting and light-colored clothing to dissipate and reflect as much heat as possible.

Hydration is also important – drinking water and replacing electrolytes lost through sweating. Light-colored urine indicates adequate hydration; dark urine is a sign of dehydration.

What does team acclimation look like?

Once team practice begins, many states require a gradual acclimatization process that phases in activities, but rules vary by state. Some states require 14 days of acclimatization, others six days, or none at all. Some states only require it for football.

Athletes who start acclimatizing early will be able to adapt their bodies to the heat more quickly and efficiently. All athletes participating in any sport, regardless of state regulations, should acclimate carefully.

Heat acclimation involves adding stress during training every few days, but care must be taken not to overstress.

For example, in football, rather than starting with full pads and full contact on the first day of practice, they might start with just a helmet for the first few days.

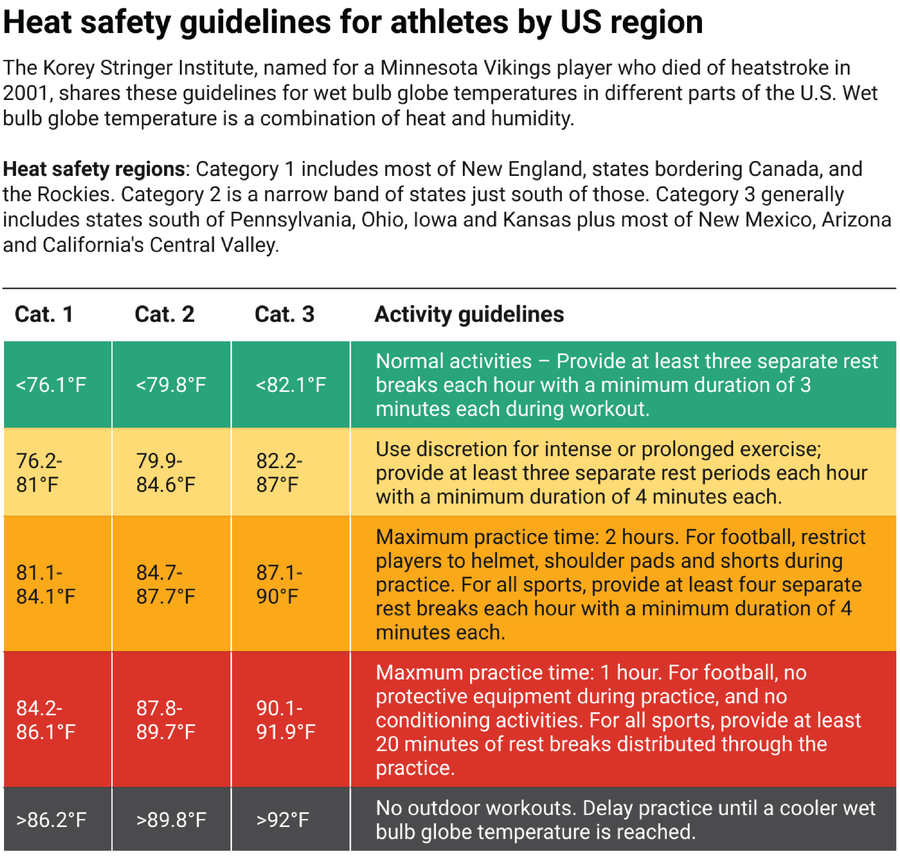

Acclimatization also involves restrictions. Initially, practicing only once a day and limiting the amount of time an athlete practices each day can help prevent the athlete’s body from being overstressed too quickly. Coaches and athletic trainers should also pay attention to the wet bulb temperature (a combination of heat, humidity, radiation, and wind speed) to gauge the risk of heatstroke to athletes and know when to limit or stop practice.

This isn’t just a football thing. Heatstroke can happen to anyone: soccer, track, softball, baseball, etc. In 2019, a Georgia basketball player collapsed and died during an outdoor practice. She was used to practicing indoors, not in the heat.

What are the warning signs that an athlete is overheating?

Players may be slowing down or becoming lethargic, which could be a sign of overheating. You may see signs of central nervous system issues, such as confusion, irritability, or disorientation. You may see someone staggering or struggling to support themselves.

In most cases, people with exercise-related heat stroke are sweating. Their skin may turn red and they may sweat profusely. Heat-stressed people may lose consciousness, but most do not.

What should you do if someone appears to be suffering from heat stroke?

If someone appears to have heatstroke, cool them down as quickly as possible. Place the person in a bathtub with water and ice. Keep their head out of the water and cool them down as quickly as possible.

A cold tub soak is best. If you can’t find a tub, put the person in the shower and put ice around it. A tarp also works. Athletic trainers call this the octopus technique: place the person in the middle of a tarp, fill it with water with ice, and lift both sides and rock them slowly, moving the water from side to side.

All sports teams should have access to cooling containers. About half of states require it. As that expands, these safety measures will trickle down to youth sports.

If a player appears to be suffering from heat exhaustion, cool him down and call 911. Having a comprehensive emergency action plan ensures all parties involved know how to respond.

What else should teams prepare?

Exercise heat stroke is a leading cause of sports-related deaths at all levels of sport, but proper recognition and care can save lives.

Athletic trainers are essential to sports programs because they are specially trained to recognize and treat patients suffering from exercise-related heat stroke and other injuries. As we experience more and more hot weather, I believe all sports programs, including high school sports programs, should have athletic trainers on hand to keep athletes safe.

This article was originally published on conversation. read Original Article.