As a huge Superman fan, I’ve been wanting to get my hands on Action Comics #419 for a long time. This issue was published in 1972 and had an iconic cover featuring the Man of Steel hurtling towards the sky, seemingly bursting from the page. That’s why I was so happy to finally find a copy in the used book section of my local comic shop earlier this year.

But I soon realized that this comic had another claim to fame. Within its pages, Superman became involved in one of the most important chapters in the history of space science.

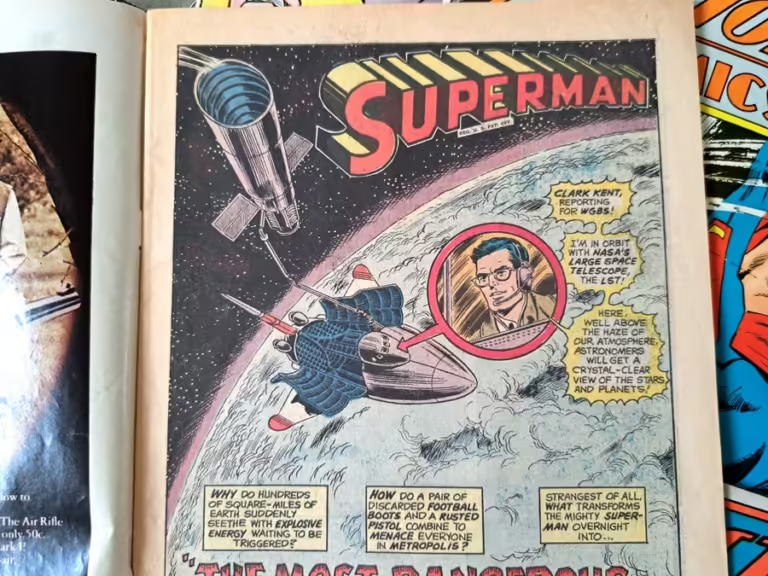

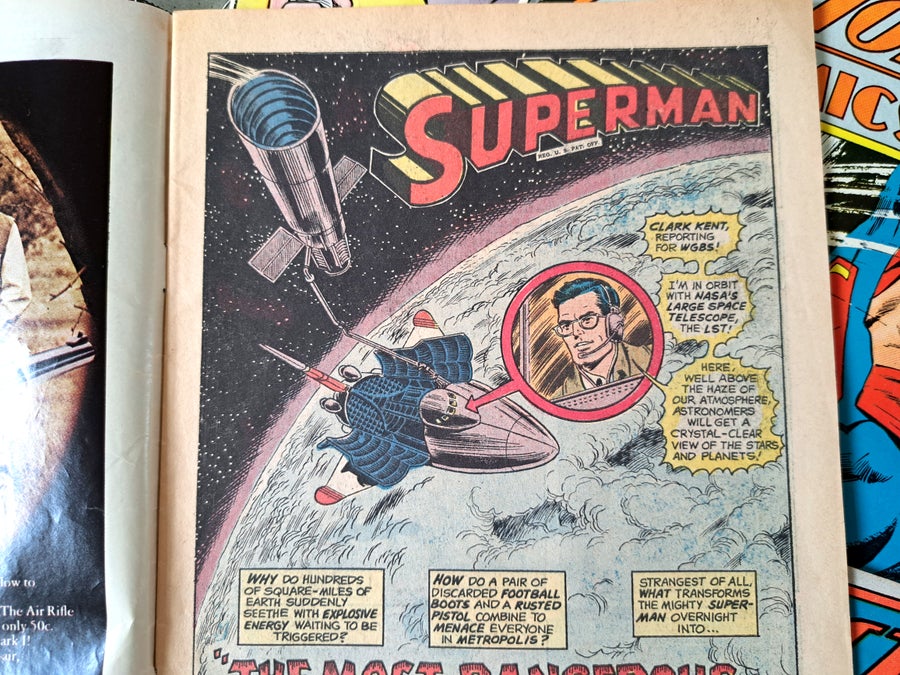

On the first page, reporter Clark Kent, Superman’s alter ego, covers the launch of NASA’s new satellite aboard the space shuttle. “I’m in orbit on NASA’s Large Space Telescope, LST, where astronomers will be able to get very clear views of stars and planets, far beyond the atmospheric haze.” Kent says in the comic.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

Right there on that page was a real-life Hubble Space Telescope dead ringer. I was confused. How did a comic book version of a space telescope launched in 1990 end up in a comic book published in 1972?

On the first page of Action Comics No. 419, Superman visits a large space telescope.

There was a hint in the credits of the story. Pete Simmons, then director of space astronomy at Grumman Aerospace Corporation (now Northrop Grumman), is credited with providing “technical assistance.” That was enough information for a Google search, which turned up a documentary clip from 1997.

What I learned surprised me. large space telescope It was Hubble. The project was named after astronomer Edwin Hubble in 1983, but NASA had been developing plans for what was called the Large Space Telescope since the late 1960s. The agency successfully launched its first space telescope, Orbiting Observatory-2 (OAO-2), in 1968, and by 1971 began feasibility studies on larger instruments to peer deeper into space. did.

But selling such an expensive project in Congress will be difficult. Simmons, who previously worked on OAO-2, took on the challenge of proving to the public, and Congress, that LST is a worthwhile scientific investment. One day while on a plane to New York, Simmons noticed a child reading a Superman comic in the seat next to him, according to an episode of the Mountain Lake PBS documentary series People Near Here. I remembered inside.

“I thought, ‘Oh, this is pretty popular,'” he said in the documentary. He invited DC Comics employees to Grumman Laboratories, showed them a model of the LST, and convinced them that the telescope should be featured in a Superman story. The result was Action Comics #419. The comic sold well, as Superman comics usually do, and gave Simmons concrete evidence of the American public’s interest in LST, which he was able to share with Congress.

“I went to Washington (DC)…and we gave every member of Congress a copy of this Superman comic,” he recalled. “I remember asking all the questions I could find…’Do you think it would be popular enough if we could get the large space telescope that was talked about in the Superman comics?’ ?’ Then give them a copy of this issue.”

I needed to know more. My two big interests, comics and space science, were colliding. Can we really get Superman to thank us for all the important discoveries and amazing images made by the Hubble Space Telescope?

Sadly, Mr. Simmons passed away in 2018. So I contacted Charles Robert O’Dell, an observational astronomer and principal scientist on the Large Space Telescope project from 1972 to 1983.

O’Dell told me that in the project’s early stages, LST’s fate was not solely in the hands of Congress. Supporters also had to convince fellow astronomers, many of whom would have preferred to spend their money on telescopes on Earth, that LST was worth the investment. .

“We organized something called a ‘dog and pony show’ with NASA engineers and managers,” he says. “(We) went to (Harvard University, University of Chicago, Caltech) and spoke at those places and called for LST conversions. And this moved people.”

However, in the eyes of astronomers, Action Comics #419 was not a selling point for LST. “It was actually a setback,” O’Dell said. “Remember how conservative astronomy was as an object back then. So looking at comics was just a foreign concept.”

Mr. O’Dell believes that the cartoon would have been really useful in persuading Congress in the hands of a natural salesman like Simmons. “[Simmons]would go along with this great salesman’s enthusiasm for this project and pull that comic out. … He was able to accomplish something like that,” O’Dell says. .

O’Dell could not confirm how much influence the cartoon had on Congress. And the telescope still faced a tough battle over funding. In 1974 and 1976, astronomers campaigned in Congress for support for the project. They sent letters and telegrams, and even made personal visits to the Reichstag.

In 1977, Congress finally approved funding for LST. Thirteen years later, the Hubble Space Telescope was launched with a new name. In operation for more than 30 years, it was the first observatory to detect elements in the early universe, image the surfaces of stars other than the Sun, and confirm the existence of supermassive black holes. And I learned that its existence is not due to fictional superheroes, but to the hard work and passion of people like Odell and Simmons.

But for some reason, I think Superman prefers it that way.