For most of the 20th century, the average life expectancy of people in developed countries increased by about three years for every successive decade. For people born in the early 21st century, these incremental growth meant that they could live an average of 30 years longer than people born in 1900, reaching their 80th birthday.

This phenomenon, called radical extension of lifespan, has been conferred on humanity by advances in various medical technologies and public health measures. Many scientists and the general public predicted that this trend would continue and that human lifespans would similarly increase indefinitely. But some predict that life expectancy in the world’s longest-lived country will plateau at well below 100 years, and that humanity will reach its natural limit.

New research on this hotly debated issue suggests that humans have indeed reached the upper limit of their lifespans. Despite continued medical advances aimed at extending lifespans, the findings show that people in the countries with the longest life expectancy have experienced a slowdown in the rate of improvement in life expectancy over the past 30 years. It shows.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

This is because so far no efforts have been made to slow aging, a poorly understood set of biological processes that lead to effects such as frailty, dementia, heart disease, and sensory impairment. Yes, says S. Jay Olshansky, a professor of public health at American University. University of Illinois at Chicago and lead author of a new study published in 2006. natural aging. “Once the warranty period has passed, our bodies no longer function properly.”

“As people live longer, it’s like playing a game of whack-a-mole,” he added. “Each mole represents a different disease, and the longer humans live, the more moles will develop and the faster they will develop.”

Olshansky became convinced that the aging problem was permanent when he published a paper in 1990. science It predicted that even if medical progress accelerated, growth in life expectancy must slow. They concluded that it is “very unlikely” that humans will live longer than 85 years.

The paper encountered widespread backlash, he says, because “there is a vested interest in this narrative that life expectancy continues to increase.”

But Olshansky was convinced he was right. So he decided to “become a patient scientist,” he says, and retest his hypotheses as real data came in. It took 34 years, but the wait has now paid off with a “definitive yes” supporting their original hypothesis. findings, he added.

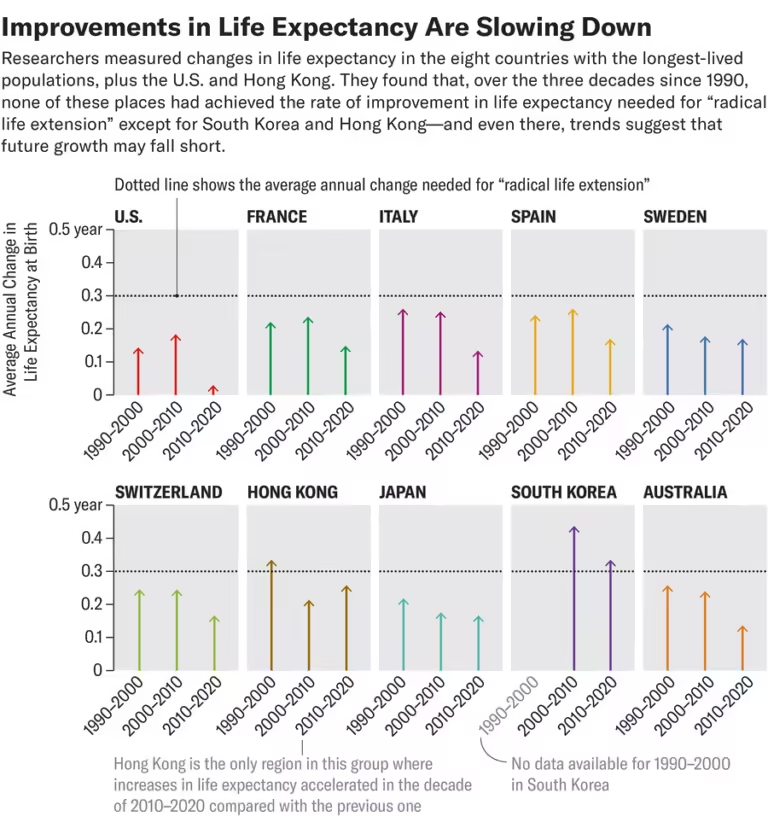

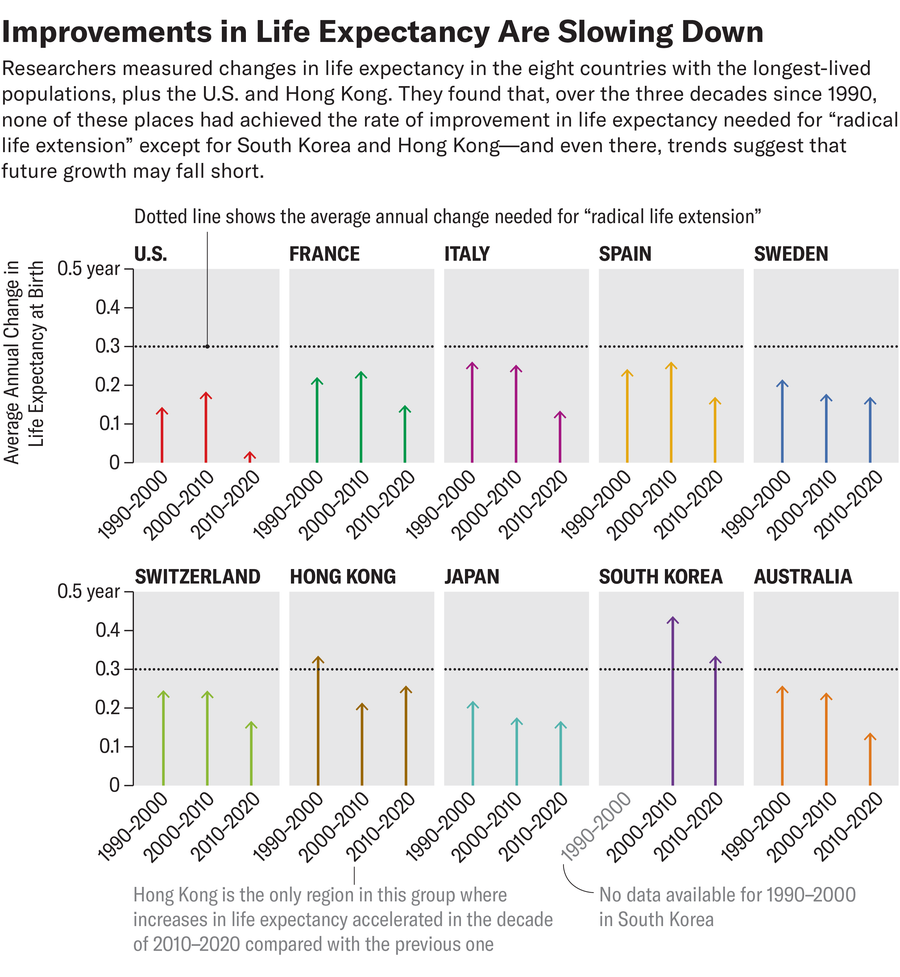

Olshansky and his colleagues took a straightforward approach. They examined changes in mortality rates and life expectancy observed from 1990 to 2019 in eight of the world’s longest-lived countries: Japan, South Korea, Australia, France, Italy, Switzerland, Sweden, and Spain. America and Hong Kong. They found that improvements in life expectancy have slowed in almost all of these regions, and that life expectancy has actually declined in the United States.

South Korea and Hong Kong were exceptions. Survival rates in both regions have improved at an accelerating pace in recent years, Olshansky said, and this phenomenon is related to the fact that both regions have seen significant increases in life expectancy concentrated in the recent past, over the past 25 years. Researchers believe that there may be. Still, in Hong Kong, which has the world’s longest-living population, just 12.8% of girls and 4.4% of boys born in 2019 are expected to reach 100, researchers found.

In the United States, the numbers are much lower, with only 3.1% of girls and 1.3% of boys expected to live to be 100 years old.

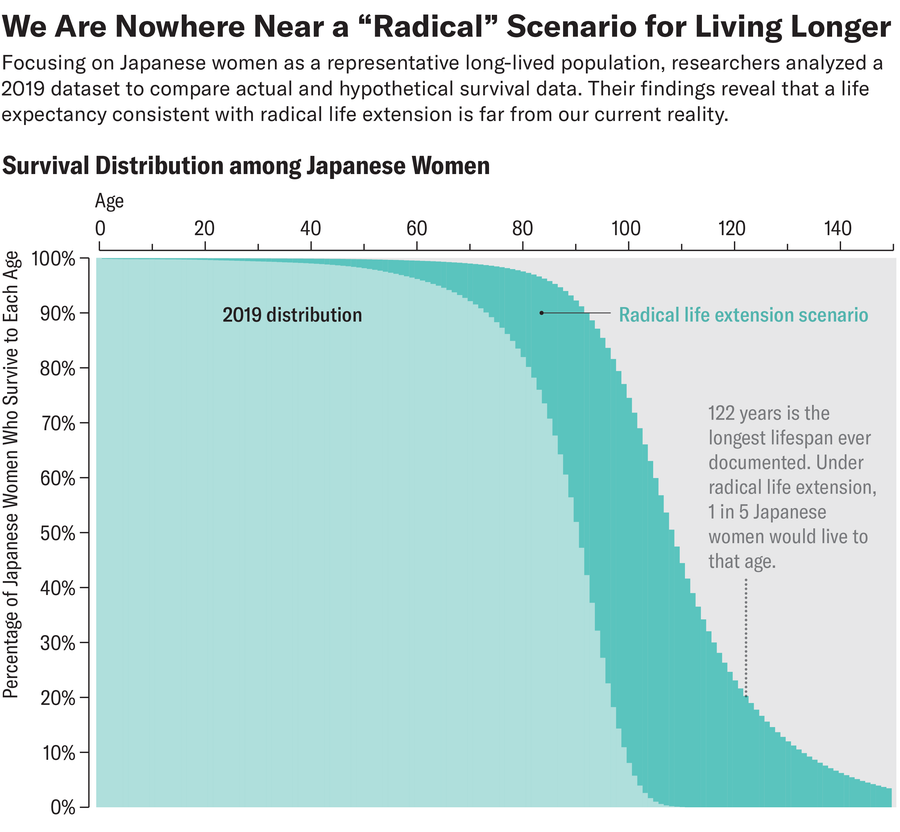

To put their findings into perspective, Olshansky and his colleagues calculated what life expectancy would be if humans actually kept pace with radical life extensions. If this were true, for example, 6% of Japanese women would live to be 150 years old, and about 1 in 5 Japanese women would live beyond 120 years old. “Even though it was a paper, we expected people to come to that conclusion for themselves,” Olshansky said.

Jan Vij, a biologist and geneticist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine who was not involved in the study, said the new paper’s approach and conclusions “make perfect sense.” “There is absolutely no evidence that living to 100 years of age will become a reality anytime soon.”

Vijg added that the new paper’s findings mirror several previous studies, including a 2016 paper he and his colleagues published that reached the same conclusion about the limits of lifespan. “After we published our paper, we were overwhelmed by an avalanche of reactions, both scientific and non-scientific, that told us we were charlatans, that the data were flawed, and that there was no evidence of a limit to lifespan.” Mr. Visig says. “Needless to say, we found no flaws in our data.”

Despite the weight of the new evidence, Olshansky fully expects his and his colleagues’ findings to be controversial.

However, scientists should shift their focus away from the “untested hypothesis” of continued fundamental lifespan extension, and instead focus on geriatrics (focusing on increasing the “healthspan” of people, i.e. the number of people in the population). He argues that we should shift our focus to relatively new fields of research. The healthy years they should enjoy, but not the overall longevity. Unless new technologies address aging itself, further dramatic life extensions in countries with already long life expectancies “remain implausible,” Olshansky and colleagues write in a new paper.

Nalini Raghavachari, a program officer at the National Institute on Aging, who was not involved in the study, agrees that research should focus on understanding and achieving healthy aging. Hints on how to do that may come from some of the world’s longest-living people, she says. “A better understanding of the protective effects and mechanisms underlying exceptional health span may lead to the development of new therapeutic targets and interventions to promote healthy aging,” Raghavachari added.