October 11, 2024

4 minimum read

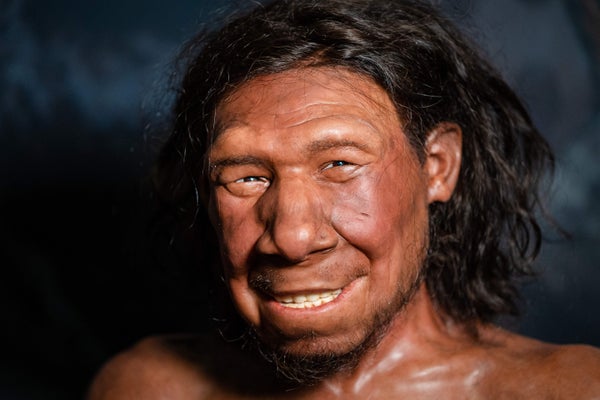

Human origins depict our ancestors as lovers, not fighters

Fossil and genetic discoveries paint an increasingly intertwined history of humans and extinct species like Neanderthals merging

The reconstructed face of Klein, the oldest Neanderthal discovered in the Netherlands, on display at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden on September 6, 2021.

Bart Maat/ANP/AFP via Getty Images

At the heart of scientific questions about human origins lie questions about human nature. teeth homo sapiens Lover or fighter in nature, predator or prey, lucky survivor or inevitable conqueror?

More and more friendly answers to these questions are coming, as evidenced by a series of genetic discoveries and recent fossil discoveries. They also highlight how difficult life was for our prehistoric ancestors. There are 8 billion people on Earth today, and that number continues to grow, but for most of human history, survival was the only victory.

Not everyone was like that. Just 200,000 years ago, our ancestors lived on a planet teeming with various human relatives. Neanderthals lived in Europe and the Middle East. Denisovans, known today only by bone fragments, teeth, and DNA, lived throughout Asia and possibly even the Pacific Ocean. “The Hobbit” homo floresiensis, A small species that lives in Indonesia, and is also called another short-stature species. Homo luzonensis, I did it in the Philippines. flat homo erectusthe grandparents of the early human species were still running around as late as 112,000 years ago.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

Now they are all gone. Except for our genes. Denisovans interbred with Neanderthals, and both interbred with modern humans. The genes of the “unknown human of Africa” also characterize the genome of modern humans. The discovery of the first of these mixtures, beginning in 2010, has challenged the previously conventional “out of Africa” picture of human origins. The idea is that a small, unique group of human ancestors developed language, which was then replaced by all other ancestors around the world within the past 100,000 years. .

Rather, the new picture of our origins is less like a family tree and more like a tangled shrub, its winding branches weaving separate human groups into today’s broader human population. Today’s humans arose primarily from the interbreeding of modern-looking humans living in Africa with disparate human populations scattered throughout the wider world. These African migrants themselves initially came from intermittent admixed populations scattered throughout the African continent.

Neanderthal genes reveal the extent of this admixture. Rather than fighting a war of extinction, modern humans and Neanderthals coexisted for at least 10,000 years in Europe and Asia, about 50,000 years ago. Or maybe even earlier, there is evidence to suggest it. homo sapiens They lived in Greece 210,000 years ago, but then ceded Europe to Neanderthals. Genetic studies suggest that this genetic exchange peaked twice, about 200,000 years ago and 50,000 years ago. If you think about it, it seems like even some of the bacteria in our mouths has Neanderthal origins. Because of that early admixture, the proportion of Neanderthals themselves averaged 2.5 to 3.7 percent. homo sapiens DNA, a contribution that later confounded family trees.

The demise of Neanderthals, who disappeared from the fossil record after 40,000 years ago, appears to be more of a demographic issue. In a 2021 study, the field of paleoanthropology largely agreed that Neanderthals’ small population size led to their extinction. A scientific report this summer confirms this. In this study, researchers at Princeton University examined repeated gene flow between humans and Neanderthals over the past 200,000 years. They found that there were 20 percent fewer Neanderthals running around than expected. There weren’t that many. They interbred and integrated into larger groups of modern humans arriving from Africa.

Neanderthal populations also took a hit as woolly mammoths, bison, and woolly rhinos, their big prey, declined during the Ice Age. A report in September of a 100,000-year-old Neanderthal from France known as “Thorin” suggests that our cousins were less likely to migrate than modern humans and were more resilient to changes in climate and landscape. It suggests vulnerability. Thorin was the descendant of a population that was genetically isolated for tens of thousands of years, even though he lived near other Neanderthals who may have later interbred with modern humans.

A similar situation of shuffled genes and small populations is forming for Denisovans and other archaic hominin species. This genetic shuffling has left humanity itself looking a little disorganized. For example, a July 2021 analysis found that “only 1.5 to 7 (percent) of the modern human genome is unique to humans.”

It’s not that much. Looking back at humanity’s scattered genetic history, scientists including Chris Stringer of London’s Natural History Museum, once a champion of the strict extra-African theory of human origins, are finding that humans, ancient fossils and genes I investigated the patchwork. Stringer et al. concluded that: nature In 2021, it states that “the specific point in time at which modern human ancestry was restricted to a limited number of birthplaces cannot currently be determined.”

Our origins therefore appear to be not particularly orderly, but complex, with many hybridizations across time and space. We were more wanderers and potential stepparents in our new territory than conquerors. Something to consider the next time you hear someone talking about their family history or how the other person is an unwanted outsider.

This is an opinion and analysis article and the views expressed by the author are not necessarily those of the author. scientific american.