aAs soon as a star is born, it begins to fight against gravity. A burning star continually releases enough energy to counteract the inward pressure of gravity. But when the fuel runs out, gravity wins. The star collapses and most of its mass becomes either a neutron star, an ultrasense object the size of a city, or a black hole. The rest explodes outward and flies into space like a bullet.

Astronomers recently captured new images of the aftermath of this violence by training the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) on the remnants of a young supernova called Cassiopeia A. Light from that explosion reached Earth about 350 years ago, around the time of Isaac Newton. “This particular object is very important because it’s relatively close and young, so what you see is a frozen picture of how the star exploded,” said Dartmouth College astronomer Robert A. Fesen says.

Astronomers have been studying this nearby spectacle for decades, but JWST has been more visible than any observatory in the past. “Webb’s images are really amazing,” Fessen says. Fesen led the first team to study Cassiopeia A with the Hubble Space Telescope. Hubble mainly observes with optical light. A range of wavelengths can be seen by the human eye, but JWST captures long-wavelength red light and does so with a larger mirror that captures higher-resolution images.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By subscribing, you help secure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

Recent photos are helping scientists answer some of the most pressing questions about supernovae. For example, which types of stars explode and how exactly do those explosions unfold? “There’s a lot of complicated but beautiful physics to understanding how this explosion happens,” says Purdue University Astronomer Danny Milisavljevic.

A star begins by burning hydrogen into helium in a fusion reactor. When hydrogen is used up, it fuses helium to make carbon, then carbon to make neon, and so on until it reaches iron. At this point, the star begins to collapse under gravity, and its matter falls away until most of the protons and electrons in the atoms slip together to form neutrons. Eventually the neutron cannot decay any further. They become neutron stars, and the particles experience extreme pressure, causing a repulsive shock wave. (Only the most massive stars end their lives in supernovae. For example, the Sun disappears to become a white dwarf.)

Astronomers still cannot fully explain the explosive power of supernovae. “This rebound shock that is generated when a star shape of neutrons can cause the star to explode was thought about,” says Milisavljevic. “But decades of simulations on the world’s fastest computers have shown that the rebound shock is not strong enough to overcome the huge layer that wants to fall.”For now, the supernova explosion The core driver of remains a mystery. Researchers suspect the answer involves neutrinos. Neutrinos are nearly massless particles that tend to pass through matter unhindered. Presumably, with the intense temperature and density at the star’s core, some of the neutrino’s energy would revive the shock. However, more observations are needed to test this idea.

Among JWST’s revelations about Cassiopeia A are layers of gas that escaped the star during its explosion. These JWST images show the gas before it interacts with material outside the star and before it is heated by reflections of the shock waves that expelled the star during its eruption. This pristine ejecta from a supernova shows well-like structures that provide clues about the star before it explodes. “JWST basically gave us a map of the structure of that material,” says Princeton University astronomer Tea Temim, who collaborated on the JWST images. “This tells us what the distribution of the material is before it’s ejected in a supernova. We haven’t been able to see anything like this before.”

The study also revealed an unexpected feature of Cassiopeia A, which scientists have dubbed the “green monster.” Astronomers think this layer of gas was expelled by the star in front It exploded. “The green monster was an exciting surprise,” says Temim. Scientists are interested in what happens when supernova debris flies into the green monster material. “This is important,” Temim says. “Because when you look at non-skid supernovae, their light is very influenced by the surrounding material.”

Deciphering the details of supernovae may even help us understand how Earth and life on it came to be. Stars create elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, which life requires. Their terminal eruptions spew these elements into space, seeding galaxies with raw materials and forming new stars and planets. “As citizens of the universe, it is important to understand this fundamental process that enables our place in space,” Milisavljevic says.

Astronomers will continue to study Cassiopeia A, but with their success they hope to turn JWST’s eyes to some of the roughly 400 other identified supernova remnants in our galaxy. Obtaining a larger sample will help researchers connect differences in how remnants look.

heavenly firecrackers

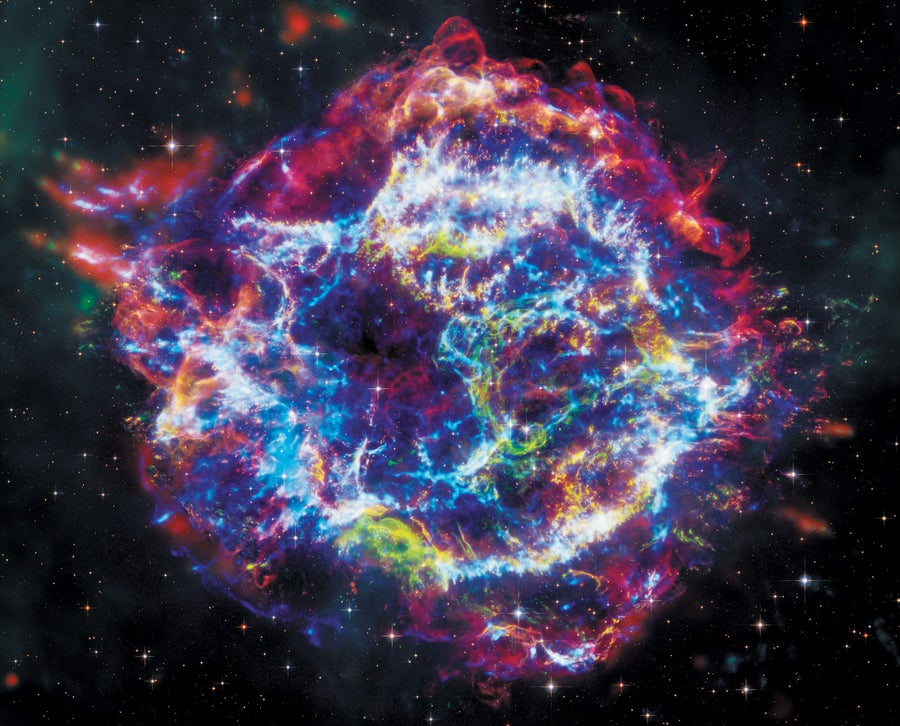

NASA/CXC/SAO (x-ray); NASA/ESA/STSCI(optics); NASA/ESA/CSA/STSCI/D. Milisavljevic et al. , nasa/jpl/caltech (infrared); NASA/CXC/SAO/j. Schmidt and K. Arcand (image processing))

Cassiopeia A is the aftermath of Earth’s closest young supernova, an explosion that occurred about 350 years ago. In this image, recent data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), combined with previous observations by the Hubble Space Telescope, Chandra X-Ray Observatory, and Spitzer Space Telescope, give us a clearer picture of Cassiopeia A than ever before. I’ll clarify.

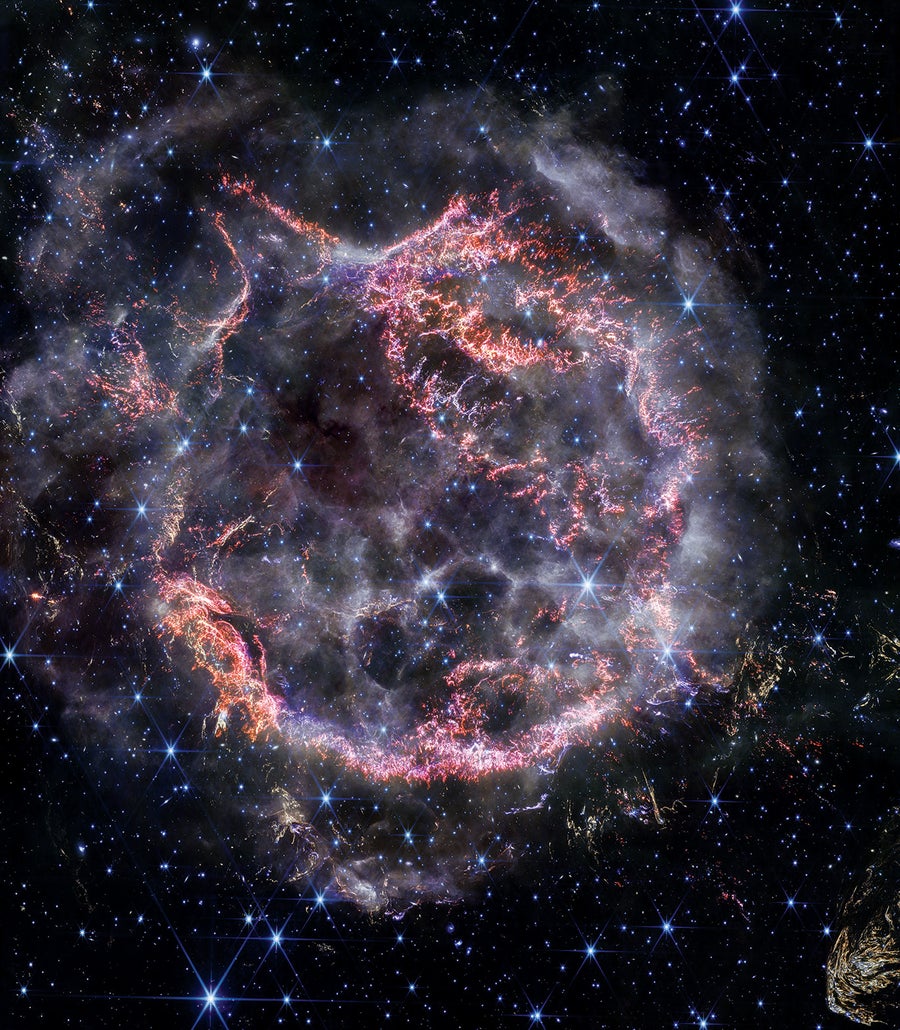

NASA, ESA, and Hubble Heritage (STSCI/AURA)-ESA/Hubble Collaboration. Acknowledgments: Robert A. Fesen/Dartmouth College and James Long/Esa/Hubble

Before the JWST images, Hubble’s observations of Cassiopeia A were revolutionary. In photos taken in 2006, Hubble improved the resolution of ground observations by a factor of 10. In the process, they were able to resolve a chunk of material ejected during a supernova that was traveling shockingly fast, between 8,000 and 10,000 kilometers per person. Number 2. “The explosions are incredibly violent,” Fessen says. “The star’s outer layer appears to fragment into clumps of gas, just as the star has been shattered into thousands of pieces.” Scientists had not realized that the explosion could produce such clumps. , says Fesen. “Nature had to show us that stars actually do that.”

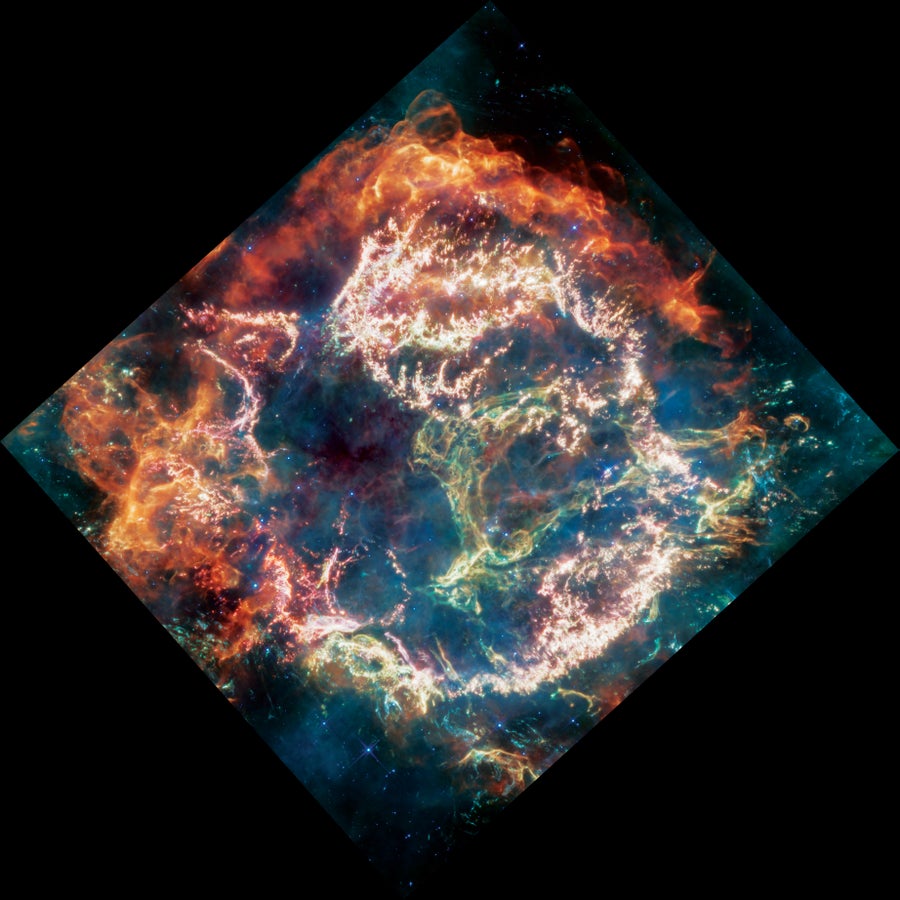

NASA, ESA, CSA, Danny Milisavljevic/Purdue University, Tea Temim/Princeton University, Ilse de Looze/University of Ghent; Joseph Depasquale/Stsci (image processing))

JWST is the most powerful telescope ever built, and Cassiopeia A’s portrait shows unprecedented detail. The observatory’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) captures different bands of infrared light, each of which is converted into a visible light color in this photo. Orange and red run across the top and left of the image, showing where material from the exploding star is colliding with the surrounding gas and dust. Inside this shell are bright pink strands that are released during the explosion. The dark red web toward the left of center represents pristine structures from the explosion that may hold clues before the star explodes.

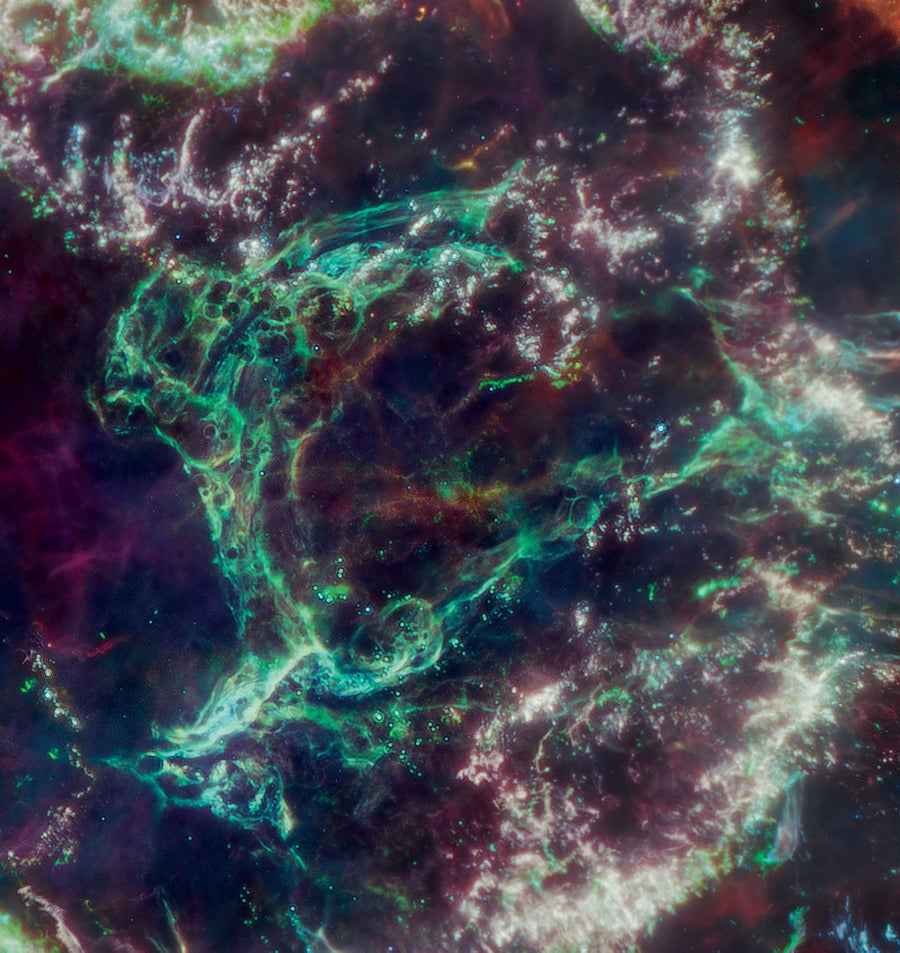

NASA/ESA JWST, Danny Milisavljevic/Purdue University, Tea Temim/Princeton University, Ilse De Looze/Ghent of Ghent, HST, R. Fesen/Dartmouth College; J. Schmidt (image processing))

Zooming in on the JWST image reveals a surprise. Green Bubble Scientists are calling it the “green monster” after the green wall at Boston’s Fenway Park. This blob is made of a layer of gas that the star casts before breaking apart. “It looks strange and has this strange distribution of rings and filaments,” Milisavljevic says. “Encoded in this puzzle is information about how the star was ejecting mass before it exploded.”

The hole seen in the green monster appears to provide evidence of the mass of Ijedafesen and his team observed with Hubble. “JWST images show little holes, almost like perfectly round bullet holes,” he says. Scientists believe that a rapidly moving mass of supernova material creates a hole by punching a sheet of surrounding gas, like shrapnel. The size of the hole belies the enormous size of the clamp: 500 astronomical units (the distance between the Earth and the Sun). “As these clumps sailed through space, they expanded to become larger than our solar system,” Fesen says.

NASA, ESA, CSA, STSCI, Danny Milisavljevic (Purdue University), Ilse de Looze (Ugent), Tea Temim (Princeton University)

Another JWST instrument, the Near Infrared Camera (Nircam), showcases Cassiopeia A with light at wavelengths shorter than a millimeter. “The advantage of Nircam is the solution,” says Milisavljevic. “When you zoom in like this, it’s amazing. I’m going to spend the rest of my career trying to understand supernovae at these scales.” He uses these data to figure out what the explosion’s shock waves encountered. We want to understand how the gas formed and how dense the supernova material is.