October 2, 2024

4 minimum read

Largest brain map ever reveals Drosophila melanogaster neurons in detail

Wiring diagram lays out connections between approximately 140,000 neurons and reveals new types of nerve cells

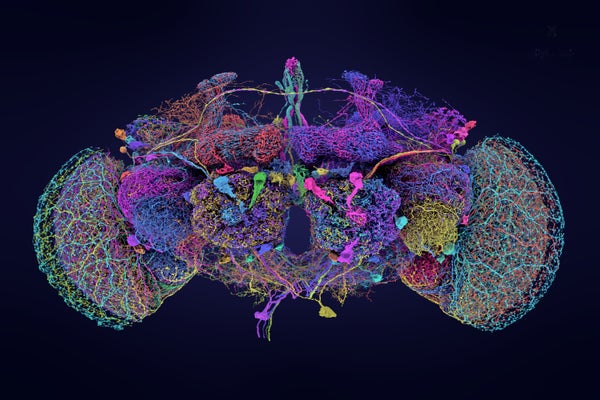

The largest 50 neurons in the fly brain connectome.

Tyler Sloan and Amy Sterling, Princeton University, FlyWire (Dorkenwald et al., Nature, 2024)

Fruit flies may not be the smartest creatures, but scientists can learn a lot from their brains. Now that researchers have a new map of a fruit fly’s brain – the most complete yet for an organism – they hope to make it a reality.Drosophila melanogaster). The wiring diagram, or “connectome,” contains approximately 140,000 neurons and records more than 54.5 million synapses, the connections between nerve cells.

“This is a big deal,” says neurobiologist Clay Reed of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, Washington. Although he was not involved in the project, he has worked with one of the team members who was. “It’s something the world has been waiting for for a long time.”

This map is described in a package of nine papers on the data published in . nature today. Its creators are part of a consortium known as FlyWire, co-led by neuroscientists Mara Marcy and Sebastian Sun of Princeton University in New Jersey.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

long road

Soong and Murthy said they have been developing the FlyWire map for more than four years using electron microscopy images of fly brain slices. With the help of artificial intelligence (AI) tools, the researchers and their colleagues pieced together the data to create a complete map of the brain.

However, these tools are not perfect and the wiring diagrams had to be checked for errors. The scientists spent so much time manually proofreading the data that they asked volunteers to help. In total, consortium members and volunteers made more than 3 million manual edits, said co-author Gregory Jeffreys, a neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge in the UK. (He points out that much of this research was done in 2020, when fly researchers were stranded and working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic.) Ta.)

But the research wasn’t finished yet. The map still needed to be annotated, a process in which researchers and volunteers labeled each neuron as a specific cell type. Jefferis likens the task to evaluating satellite imagery. While AI software might be trained to recognize lakes or roads in such images, a human would need to review the results and name the particular lake or road itself. Overall, the researchers identified 8,453 types of neurons. This was much more than anyone expected. Of these, 4,581 will be newly discovered, which will lead to new research directions, Sun said. “All of these cell types are questionable,” he added.

The research team was also surprised by some of the ways different cells connect with each other. For example, neurons that were thought to be involved in only one sensory wiring circuit, such as the visual pathway, tended to receive cues from multiple senses, including hearing and touch.1. “It’s amazing how interconnected the brain is,” Marcy says.

explore the map

FlyWire map data has been publicly available for researchers to explore for the past several years. This has allowed scientists to learn more about the brain and fruit flies. The discovery is nature today.

For example, in one paper, researchers used the connectome to create a computer model of the entire Drosophila brain, including all the connections between neurons. They tested it by activating neurons known to detect sweet or bitter tastes. These neurons then send a cascade of signals through the virtual fly’s brain, ultimately triggering motor neurons attached to the fly’s proboscis (the mammalian equivalent of the tongue). When the sweet taste circuit was activated, it sent a signal that caused the insect to extend its proboscis, as if preparing to feed. This signal is inhibited when the bitter circuit is activated. To test these findings, the research team activated the same neurons in real fruit flies. The researchers found that the simulation was more than 90% accurate in predicting which neurons would respond and therefore how the flies would behave.

In another study, researchers describe two hard-wired circuits that signal flies to stop walking. One of them contains two neurons that are responsible for stopping the “walking” signal sent by the brain when the fly wants to stop and feed. Another circuit contains neurons in the nerve cord that receive and process signals from the brain. These cells create resistance in the fly’s leg joints, allowing the insect to stop while preening.

One limitation of the new connectome is that it was created from a single female Drosophila. Drosophila brains are similar, but not identical. Until now, the most complete connectome of the Drosophila brain was a map of the “half-brain,” a part of the fly’s brain containing about 25,000 neurons. One of them is nature In a paper published today, Jefferis, neurobiologist Davi Bock of the University of Vermont in Burlington, and colleagues compared flywire brains to hemibrains.

Some differences were noticeable. FlyWire’s flies had nearly twice as many neurons in a brain structure called the mushroom body, which is involved in the sense of smell, compared to the flies used in the hemibrain mapping project. Bock believes this discrepancy may be because the hemibrain flies were starved while they were still growing, negatively impacting their brain development.

FlyWire researchers say much work remains to fully understand the fruit fly brain. For example, modern connectomes only show how neurons connect through chemical synapses, where molecules called neurotransmitters transmit information. No information is provided about the electrical connections between neurons or how neurons communicate chemically outside the synapse. Marcy also hopes to eventually obtain the male fly’s connectome, allowing researchers to study male-specific behaviors such as singing. “This isn’t the end, but it’s a big step,” Bock said.

This article is reprinted with permission. first published October 2, 2024.