Hidden among the towering mountains of Central Asia and along the so-called Silk Road, archaeologists have unearthed two medieval cities that may have been bustling with people a thousand years ago.

Researchers first noticed one of the lost cities in 2011 while hiking through the grassy mountains of eastern Uzbekistan in search of untold history. Archaeologists walked along the river bed and discovered the burial site on their way to the top of the mountain. When we got there, we found a vast plateau dotted with strange mounds. To the untrained eye, these mounds would not have looked like much. But “as archaeologists… (we) recognize that they are human-made sites, places where people live,” says Farkhod Makhdov of the National Archaeological Center of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences.

Thousands of pottery shards were also scattered on the ground. “We were kind of shocked,” said Michael Frachetti, an archaeologist at Washington University in St. Louis. He and Makdoff were looking for archaeological evidence of a nomadic culture that grazed herds in mountain meadows. The researchers didn’t expect to find a 30-acre medieval city in a relatively harsh climate some 7,000 feet above sea level.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

But this place, called Tashbulak, after the area’s current name, was just the beginning. During excavations in 2015, Frachetti met with one of the area’s only remaining inhabitants, a forester who lives with his family a few miles from Tashbulak. “He said, ‘I’ve seen pottery like that in my backyard,'” Frachetti recalled. So the archaeologists drove to the forester’s farm, where they discovered his house perched on a familiar mound.

“Sure enough, he lives in a medieval citadel,” Frachetti says. From there, researchers took in the view and identified more mounds. “And we’re like, ‘Oh my God, this place is huge,'” Frachetti added.

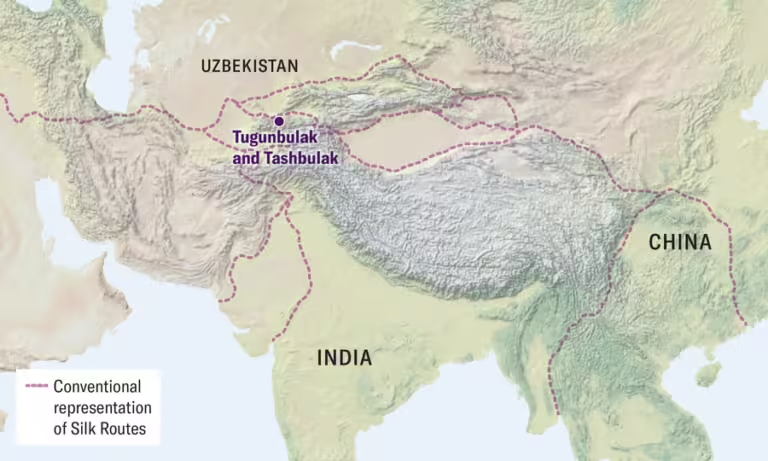

This second site, named Tugumburak, was first described in a study published on October 23. Nature. Researchers used remote sensing technology to map the sprawling medieval city of nearly 300 acres, three miles from Tashbulak, that was integrated into the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road.

“This is a pretty remarkable discovery,” says Zachary Sylvia, an archaeologist at Brown University who studies the history and culture of Central Asia during this period. (Although Sylvia was not involved in the new work, he wrote a commentary about it, which was published in the same issue of the magazine. Nature.) Further excavations are needed to confirm the extent and density of Tugumburak, but “even if it turns out to be half the size[estimated here]it’s still a big find,” he says. – and it may force a rethink about how vast the Silk Road network was.

In traditional maps of the Silk Road, trade routes across the Eurasian continent tend to avoid the mountains of Central Asia as much as possible. Low-lying cities such as Samarkand and Tashkent are thought to have had the arable land and irrigation facilities necessary to support thriving populations and were true destinations for trade. Meanwhile, the nearby Pamir Plateau, where Tashbulak and Tugubulak are located, is rugged and largely unsuitable for cultivation due to its high altitude. (Currently, less than 3% of the world’s population lives at higher altitudes than 2,000 meters (approximately 6,500 feet) above sea level.)

However, despite limited resources and frigid winters, people lived in Tashbulak and Tugubulak from the 8th century AD to the 11th century AD during the Middle Ages. Eventually, slowly or all at once, the settlements were abandoned and left to the elements. In the mountains, the landscape changed rapidly, and the remains of the city were worn away by erosion and covered with mud. A thousand years later, what remains are hills, plateaus, and ridges that are difficult to comprehensively map with the naked eye.

The cityscape of Tgunburak seen from a drone.

To get a detailed picture of the land, Frachetti and McDoff equipped their drones with a remote-sensing technology called lidar (light detection and ranging). Drones are strictly regulated in Uzbekistan, but the researchers managed to obtain the necessary permits to fly them in the field. LIDAR scanners use laser pulses to map features of the land below. This technique is increasingly being used in archaeology, and in recent years has helped discover a lost Mayan city spread beneath the canopy of Guatemala’s rainforest.

At Tashbulak and Tugubulak, the result was a three-dimensional map of the ruins with inch-level detail. With the help of computer algorithms and manual tracking and excavation, the researchers mapped out subtle ridges that may represent walls or other buried structures.

Sylvia said this method has its limitations, meaning it frequently produces false positives. It is also impossible to confirm which features date to which period without further excavation. While such work is ongoing in Tashbulak, it has just begun in Tugubulak. (The scans and some excavations were completed in 2022, and Frachetti’s team returned to Tugunburak this summer to continue excavating. The researchers have not yet made their findings public.) For now, Tugunburak The lidar map appears to show a large medieval complex. It has a citadel, buildings, courtyards, squares and paths, and is surrounded by fortified walls. In addition to pottery, the team also unearthed kilns and clues that workers in the city were smelting iron ore, Frachetti said.

Medieval pottery excavated at Tugumburak.

Metallurgy could be an important part of how cities can survive at such high altitudes. The mountains are rich in iron ore and contain dense juniper forests that can be burned as fuel for the smelting process. Researchers have also found coins from all over present-day Uzbekistan, suggesting the city may have been a trading center, Maksudov said. Strictly speaking, it seems that this was not a mining village either, as the Tashbrak cemetery contains the remains of women, elderly people, and infants.

“We realized that this was a metropolitan center that was integrated into the Silk Road network and that dragged the Silk Road caravans towards the mountains…because they were offering a unique product.” says McDoff.

“There is a connection” between highland and lowland cities, said archaeologist Sanjot Mehender, director of the Tang Silk Road Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley. The Silk Road’s trade networks were “very fluid,” she says, and even societies that were once considered peripheral and remote, such as Tashbulak and Tugubulak, “were part of a network that stretched across Eurasia.” “We can no longer look at these areas and perceive them as remote or underdeveloped.”

After completing his research on lidar, Mehendele became involved in the work at Tugumburak, and went there this summer to conduct excavations. Her main interest now is restoring what the city was like during its lifetime. Who were the residents? How did the population change over the seasons and centuries?

The answers to all these questions may be buried in the sediment. The research team “has a lifelong job,” Sylvia said.