January 2, 2025

5 minimum read

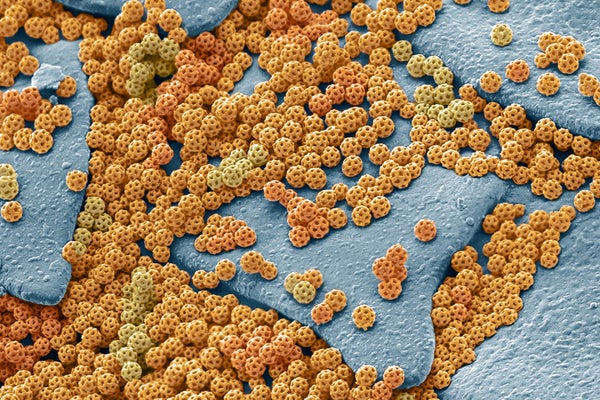

Nanotech scientists design ingenious camouflage based on insect’s bizarre soccer ball-like excrement

Man-made versions of nanoscale soccer ball-like structures called brocosomes could be used in new forms of military camouflage, self-cleaning surfaces or making hydrogen fuel

Science Photo Library/Alamy Stock Photo

In the early 1950s, Brooklyn College biologists used electron microscopy to determine how leafhoppers, a common insect the size of a grain of rice and named for one of its characteristic behaviors, are responsible for virus transmission. They were pursuing clues that it could be an intermediary. During the study, the scientists happened to observe “some kind of ultra-fine object that had not been described before” on the wing of the leafhopper. In a 1953 memo, Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological SocietyThey named these tiny, spherical, jack-like structures “brocosomes,” after the Greek word for “web.”

Since then, a slim but determined lineage of scientists and engineers has built a superspecialty around brocosomes. These researchers have made these sub-pinpoints of highly structured materials possible due to the biological wonders they embody and the technological possibilities suggested by their elaborate porous shapes and physical properties. I’m attracted to Brocosome enthusiasts do not hesitate to share their joy at discovering such a masterpiece of evolution.

“Our group first became interested in brocosomes around 2015, drawn by their nanoscale dimensions and complex three-dimensional geometries like buckyballs,” said Penn State University Biomedical Sciences. and mechanical engineer Thaksin Wong. “We were surprised at how leafhoppers can consistently produce such complex structures at the nanoscale, especially using our state-of-the-art micro- and nanofabrication techniques. , given that we still struggle to achieve such uniformity and scalability.”

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

Like others interested in these structures, Wong parlays his envy toward brocosomes into a curious technology based on brocosomes’ ability to absorb a specific range of visible and ultraviolet wavelengths. We are working towards creating a cabinet that collects the following. Wong, along with partners at Pennsylvania State University and Carnegie Mellon University, has two patents in the United States and other patents pending for processes to produce synthetic equivalents of brocosomes.

Wong said the synthetic brocosomes can be used for applications such as anti-reflective and camouflage materials, anti-counterfeiting, data encryption, and “optical security” tactics that make hidden information visible only when illuminated with infrared or ultraviolet light. It states that it is potentially suitable for a variety of applications. light. The researchers were able to secure a grant from the Office of Naval Research. The Office of Naval Research is constantly exploring ways to make it harder for adversaries to detect and track naval vessels, aircraft, and other U.S. military assets.

Wong points out that much of the recent research and development inspired by brocosomes around the world stems from the super anti-reflective upgrades that naturally produced brocosomes are added to the bodies of leafhoppers. This isn’t just cool optical physics. This light trick allows insects to sneak up on the leaf surface where hungry insects, birds, and spiders forage for prey.

Several forays into brocosome biology have shown that these natural nanoscale innovations have been linked to proteins that assemble into stealth-forming nanospheres within specialized compartments of insect Malpighian tubules, kidney-like excretory organs. It turns out that it is composed of lipids. With its hind legs, the insect grooms its entire tiny body with microscopic droplets filled with brocosomes from its anus, resulting in a light-absorbing mantle that helps it live another day.

But nanospheres are suitable for more than just concealment. In the latest addition to a growing list of brocosome-inspired technology concepts and prototypes, Wong’s Penn State team joins Carnegie Mellon researchers led by mechanical engineer Shen Shen , aims to provide new materials not only for camouflage but also for new security. The same goes for cryptographic devices. This technology takes advantage of humans’ inability to perceive infrared light.

As the researchers measured optical and other physical aspects of the synthetic brocosomes, they found that “while these structures appeared identical under visible light, they showed dramatic contrasts in infrared images.” Mr. Shen said that he noticed that. And that gave rise to the idea of encryption and security techniques, which researchers are now pursuing. The research team is considering whether it is possible to encode infrared information invisibly within the visible spectrum. Small dots of such infrared-active brocosome material on currency can act as a sign of authenticity and pose an additional hurdle for would-be counterfeiters.

Researchers have investigated six ways to produce synthetic brocosomes of various sizes and shapes. The use of various polymer, ceramic and metal materials makes TechnoCuriosity’s brocosome-inspired cabinets increasingly eye-catching.

A team of Chinese researchers who are fans of brocosomes recently reported a process for creating a vibrant spectrum of color-giving particles by filling small depressions (“nanobowl” spaces) on silver brocosome structures with tiny polystyrene spheres. did. When the researchers tuned the size of the spheres using a precision etching method, they were able to fine-tune the electromagnetic interactions between the spheres, thereby fine-tuning the apparent color of the synthetic brocosome structures. . in ACS nano In a paper in which the researchers developed their color-making strategy, they suggested that this opens the door to producing longer-lasting and more stable colors compared to short-lived chemical dyes and pigments.

Another Chinese research group sought to emulate the masters of disguise in chameleons, cephalopods, and other creatures by creating tungsten oxide-based brocosome structures that become less reflexive when stimulated electrically. One endpoint of this effort could be energy-saving applications, windows that can control the amount of solar and thermal energy that passes through them throughout the day.

A more extensive and eclectic to-do list includes light-harvesting electrodes that generate and corral energized electrons to create hydrogen fuel, and self-cleaning surfaces that repel liquids and adhesives. Also on the list are sensors that can be customized to detect specific bacteria or proteins for environmental monitoring and health applications. Additionally, there is the prospect that the pores and surface of brocosome-inspired particles could be tailored to deliver specific drugs to target tissues.

Although the potential seems huge, the prospect of an era of brocosome-inspired technology is not imminent. “One of the major bottlenecks to the widespread use of synthetic brocosomes is the lack of scalable manufacturing techniques.The complex 3D shape and nanoscale dimensions of synthetic brocosomes remain difficult to replicate at scale. Because there is,” warns Wong.

Regardless of whether his particular brocosome-inspired technology makes it to the finish line, Wong says he loves sharing his research with his non-scientist family and friends. “They are immediately fascinated by the beauty of the brocosome’s soccer-ball-like structure,” he says. “When I explain that this structure is about one-hundredth the diameter of a human hair, they can hardly believe it.”

Meanwhile, Shen welcomes the humbling side of this research romance with brocosomes. “This is a powerful reminder that innovation doesn’t necessarily have to come from human ingenuity,” he says. “Sometimes nature has already solved the problem we are working on.”