September 19, 2024

4 Time required to read

Obesity treatment pioneer receives prestigious Lasker Prize in Medicine

Three scientists honored for developing blockbuster weight loss drug. Could a Nobel Prize be on the horizon?

Joel Habener (From the left), Lotte Bjelle Knudsen and Svetlana Moysov were awarded the 2024 Lasker Award for their development of drugs to treat obesity, diabetes and other conditions.

Joel Habener, Soren Svendsen, and Chris Taggart (Courtesy of Rockefeller University)

Three scientists involved in the development of blockbuster anti-obesity drugs that are currently transforming medicine are among this year’s recipients of the prestigious Lasker Award. The award, which recognizes important advances in medical research, is often seen as an indicator of whether a particular advancement or scientist will win a Nobel Prize, and some speculate that this may soon happen for weight-loss treatments.

Joel Habener, Svetlana Moysov and Lotte Bjelle Knudsen, who helped develop a popular anti-obesity drug that mimics a hormone called glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), which lowers blood sugar and controls appetite, will share the Lasker Award for Clinical Research, which will earn them a joint prize of $250,000.

Biomedical scientists are excited about the growing awareness of GLP-1 research, which was originally aimed at treating diabetes. “I’ve been working on this for 30 years, and for a long time no one was interested,” says Randy Seely, an obesity specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “That’s changed a lot in the last few years. Now we have treatments that actually help people.”

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

Other Lasker Award winners this year include Zhijian James Chen of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas, who was honored in the basic research category for his discovery of how DNA triggers immune and inflammatory responses. In the public service category, Salim Abdul Karim and Kwaraisha Abdul Karim of the Center for AIDS Research Programs in Durban, South Africa, were recognized for their development of life-saving approaches to prevent and treat HIV infection.

Inside the Science

Havener, an endocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, pioneered the discovery of the GLP-1 hormone in the 1980s. He was interested in understanding the hormone’s role in type 2 diabetes, a condition characterized by high blood sugar, in which the body either doesn’t produce enough insulin or has trouble using insulin to absorb sugar from the blood.

Habener zeroed in on glucagon, a hormone that raises blood sugar levels. After cloning the glucagon gene, he discovered that it also coded for a related hormone (later named GLP-1) that stimulates the pancreas to produce insulin.

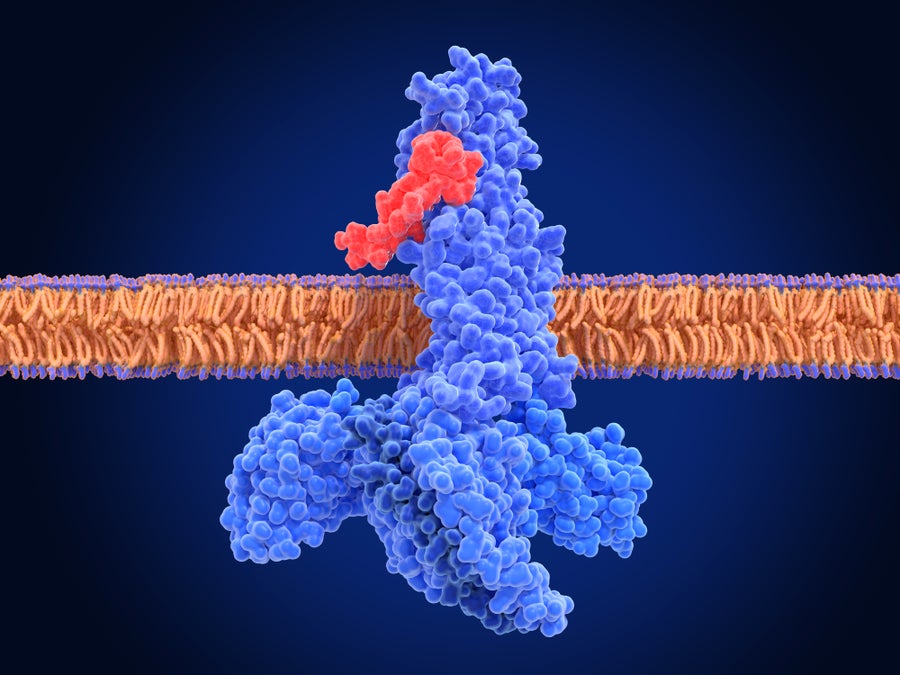

Diagram of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor (Blue) Binds to the semaglutide molecule (red), forming an activated complex. Semaglutide is a GLP-1 receptor agonist, a type of drug that mimics the function of the natural GLP-1 hormone.

Juan Gartner/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

“What’s interesting is that rather than giving diabetic patients insulin injections to control their blood sugar levels, giving them GLP-1 would theoretically encourage their body to make its own insulin,” Habener says.

Moisov, a biochemist who then headed a facility at Massachusetts General Hospital that makes synthetic proteins, identified the sequence of amino acids that make up the biologically active form of GLP-1. She eventually demonstrated that this active form could stimulate insulin release from the pancreas in rats, a necessary step on the road to a human treatment.

Moisov, now at Rockefeller University in New York City, complained last year that she felt her contributions to the field were under-recognized. Since then, she has won awards, including the VinFuture Prize. “It’s nice to receive an award, but what’s even nicer is that people are actually reading my work,” she says.

After their initial discoveries about GLP-1, researchers realized there was a big obstacle to its therapeutic use: the hormone is rapidly metabolized and lasts only a few minutes in the blood. That’s where the work of Knudsen, a scientist at the Copenhagen-based pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, came in. She and her team realized that regular GLP-1 wouldn’t work as a drug, Knudsen says. Instead, the researchers devised a way to modify GLP-1 by attaching fatty acids to it. This modification allowed the molecule to remain active in the body for longer periods before being broken down.

This research resulted in the creation of liraglutide, the first long-acting GLP-1-based drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in 2010. Meanwhile, researchers were already studying the weight loss effects of this drug, and in 2014, liraglutide became the first molecule of its class approved for the treatment of obesity. Currently, new variants such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, marketed as Wegovy and Zepbound, are important obesity treatments.

“We want to inspire young people to know that you can do great science in the pharmaceutical industry,” Knudsen says.

Is a Nobel Prize on the horizon?

GLP-1-based drugs are not only effective in treating obesity and diabetes: studies have shown they are effective in treating a variety of diseases, including cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea, and kidney disease. These benefits are thought to stem from the drugs’ effects on the brain and their anti-inflammatory properties.

The revolution these drugs are having on medicine has led some to believe they may soon receive the Nobel Prize, the highest award in science. The Lasker Award often precedes the Nobel Prize. Since 1945, 95 Lasker Award winners have also received this highest honor. “This raises concerns that the Nobel committee will take (GLP-1 research) seriously,” Seely says. The Nobel Prize will be announced next month. Each scientific award is limited to three winners, making it a challenge to choose the most deserving winner. Other scientists involved in research on GLP-1-based drugs have been honored with other awards. They include Jens Juer Holst of the University of Copenhagen, Daniel Drucker of the University of Toronto in Canada, and Richard DiMarchi of Indiana University Bloomington. “It’s 10,000 ants that move an anthill. We’re trying to pick the three that made the biggest difference,” Seely says. “I can think of at least a dozen names that have made important contributions to the field.”

This article is reprinted with permission. First Edition September 19, 2024.