January 7, 2025

2 minimum read

Plant photosynthetic machinery functions within hamster cells

The transplanted chloroplasts lasted two days inside the animal cells and then began working.

Researchers transplanted algal chloroplasts into Chinese hamster cells (Chryceturus griseus).

Junior Building Dalhiff GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo

More than a billion years ago, hungry cells devoured tiny blue-green algae. But rather than the former simply digesting the latter, the duo struck a surprising evolutionary deal. Now, scientists are trying to make that miracle happen in the laboratory.

In a recent experiment reported in Japan Academy Proceedings Series B, The researchers transplanted the algae’s photosynthetic offspring, plant organelles called chloroplasts, into hamster cells, where they converted light into energy and remained active for at least two days.

In 2021, biologist Yukihiro Matsunaga from the University of Tokyo reported how the sacoglossan sea slug “steals” chloroplasts from the algae it feeds on, allowing it to meet the slug’s energy needs for several weeks. His team wanted to replicate this mechanism in other animal cells.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

Scientists have previously tried transferring plant chloroplasts into fungal cells, but the cell’s scavenging forces destroyed the foreign organelle within hours. For this effort, Matsunaga and his group harvested extremely durable chloroplasts from red algae that thrive in acidic volcanic hot springs and placed them in hamster ovary cells grown in the lab.

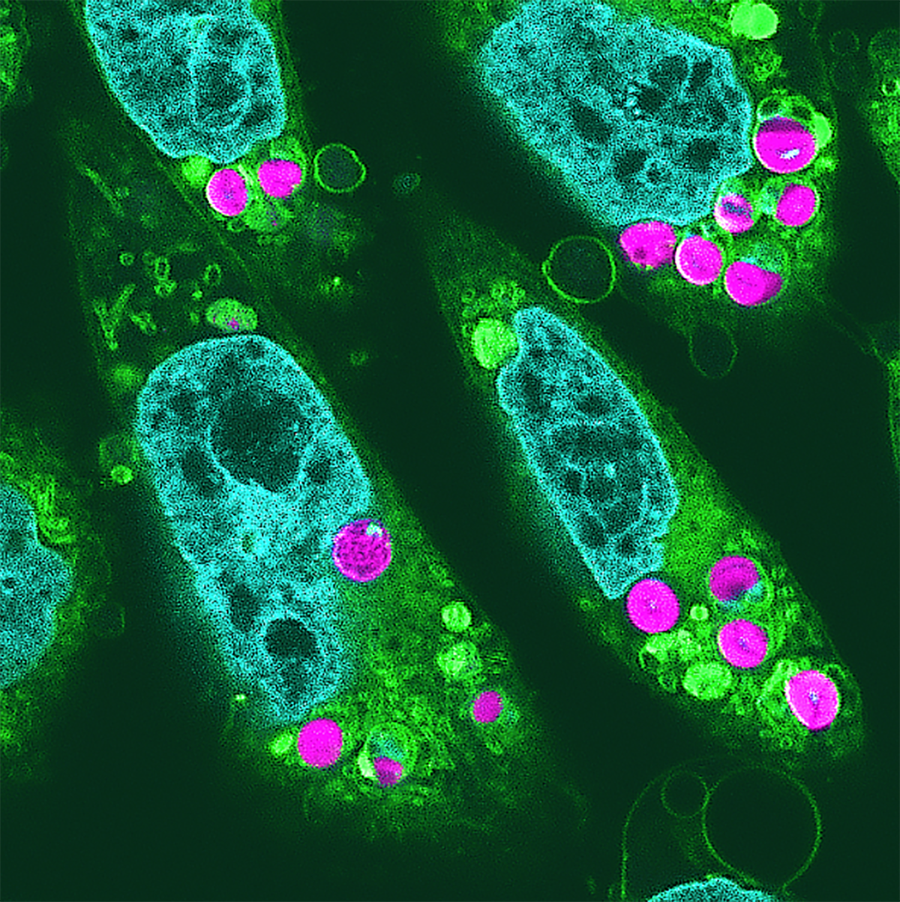

Fluorescence image shows chloroplasts (Magenta) is successfully taken up by hamster cells, highlighting other features of animal cells: the nucleus is light blue and the organelles are yellow-green.

“Incorporation of photosynthetically active algal chloroplasts into cultured mammalian cells for animal photosynthesis”, Ryota Aoki et al. Japan Academy Proceedings Series B, Vol. 100, No.9; 2024 (CC BY-NC-ND)

The research team isolated chloroplasts from algae cells using a centrifuge and gentle agitation. Instead of punching holes in host cell membranes as in previous studies, the researchers adjusted the composition of the culture medium to induce the animal cells to engulf the chloroplasts like an amoeba, allowing them to “pick up nutrients”. I made a mistake,” Professor Matsunaga said.

The transplanted chloroplasts maintained their structure for two days before degrading and were able to successfully conduct electron transfer, a key step in processing light. Previous attempts to transplant chloroplasts into foreign cells only worked for a few hours. “I’m impressed that they were able to accomplish so much,” said cell biologist Jeff D. Bork of New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.

Challenges still remain. Chloroplasts require a steady supply of protein from the cell. “However, animal cells do not have the genes necessary to produce and transport these proteins, and without them the chloroplasts quickly break down,” says Max Planck Biophysical Research in Frankfurt. says structural biologist Werner Kuhlbrandt. Like Bouquet, he was not involved in the new study. Matsunaga’s team next plans to insert genes that maintain photosynthesis into animal cells, with the aim of making them more compatible with the transplanted chloroplasts.

These types of implants could one day help scientists manipulate biomaterials, Bouquet says. Examples include photosynthetic fungi and bacteria that could be used on rooftops to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, or experimental organoids that could use the extra oxygen in chloroplasts to grow faster. Of course, a solar-powered human being is pure fantasy, but Matsunaga says, “They would need a tennis court’s worth of surface area covered in chloroplasts.”