September 5, 2024

5 Time required to read

Scientists make skin transparent in live mice using simple food coloring

The new study utilized the highly absorbent dye tartrazine, used as a common food coloring, Yellow No. 5, to make tissue in living mice transparent, temporarily exposing the animals’ organs and blood vessels.

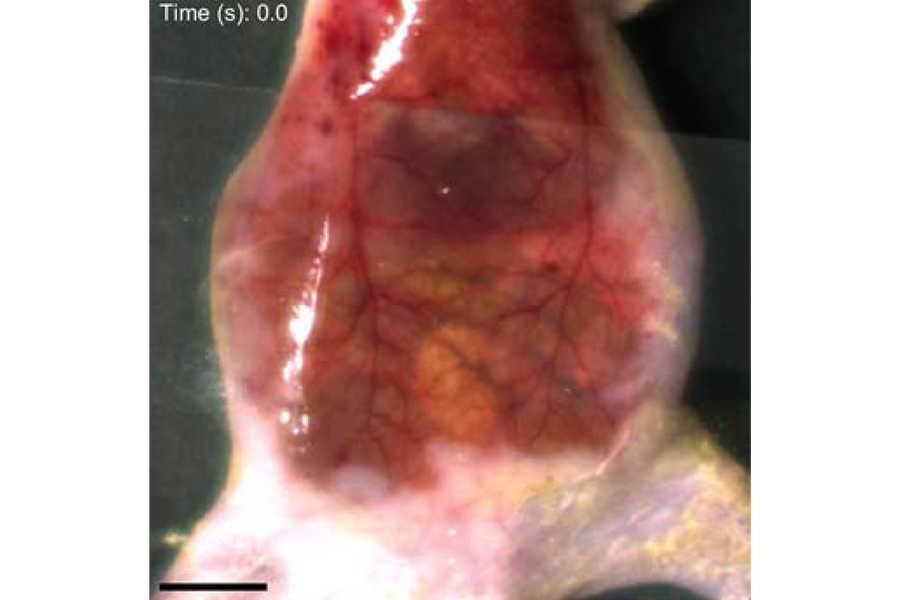

Normally, skin scatters light, a phenomenon represented by the white lines at the beginning of this clip. But when Yellow No. 5, a dye used in food, drugs, and cosmetics, is absorbed by the skin, scattering is reduced, allowing light to penetrate deeper and make the tissue clearer. (This technology has not been tested in humans. Dyes can be harmful. Always use caution with dyes and do not ingest them directly, apply them to people or animals, or misuse them in any other way.)

Keyi “Onyx” Li/National Science Foundation

In just a few minutes, you can paint your mouse with common food coloring and make any desired area of skin as transparent as glass.

In a study published today, Science, The researchers painted live mice with a solution of tartrazine, a dye commonly used in food, drugs, and cosmetics, making the mice’s tissues transparent and creating a temporary window into their internal organs, muscles, and blood vessels. The procedure, a new technique known as “optical tissue clearing,” has not yet been tested in humans, but it may one day offer a way to observe and monitor injury or disease without the need for specialized imaging equipment or invasive surgery.

“One of the unique aspects of our strategy is that we directly alter the optical properties of the tissue,” says Zhihao Ou, a physicist at the University of Texas at Dallas and the study’s lead author.

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

Skin, like most mammalian tissues, is highly opaque because the mixture of water and densely packed lipids, proteins, and other essential molecules scatters light in all directions. “The concept is similar to bubbly water,” Ou explains. “If you have water and air, both are transparent separately. But when you mix them together, they form microbubbles that are no longer transparent.” Think of rapids or crashing waves. The reason for the change in transparency is that the refractive indexes of water and air molecules (the amount of light that bends as it passes through an object or substance) are different. The fats and proteins in rodent and human skin typically have a higher refractive index than water, creating a contrast that makes it difficult to see through. In the new study, Ou and his colleagues looked for light-absorbing molecules that could make the various refractive indices within the layers of skin more similar, essentially reducing the amount of light that scatters throughout.

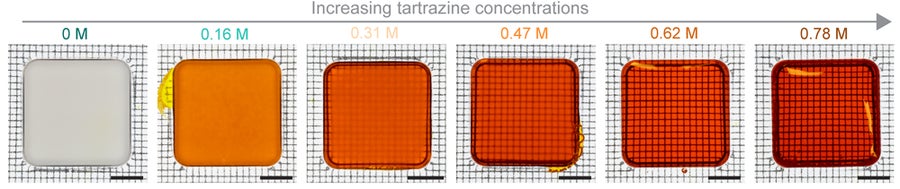

Photo of a “scattering phantom,” a sample made of agarose hydrogel that mimics the optical distribution of human tissue. The phantom contains increasing concentrations of tartrazine and the same concentration of silica particles. The scale bar represents 5 millimeters.

Guosong Hong/Stanford University

The team investigated 21 synthetic dyes, eventually landing on Tartrazine (commonly known as Yellow No. 5), which is highly absorbent. This bright lemon-yellow colorant is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in small amounts in food, drugs, and cosmetics. It is commonly found in potato chips, soda, candy, butter, vitamins, and medicine tablets. Tartrazine makes the refractive index of the molecules it encounters more uniform, allowing red and yellow light, which resemble the color of the underlying tissue, to pass through. At the same time, the dye absorbs most of the near-ultraviolet and blue wavelengths of light, reducing the scattering of those types of light. “The higher the absorption, the more efficient the molecule,” Oh explains. FDA restrictions on chemicals and additives in food lead the food industry to look for “highly efficient chemicals” in small amounts.

Animated stills from a real-time imaging video show the dynamic process of chicken breast tissue changing from opaque to transparent after immersion in a 0.6 molar solution of tartrazine (Yellow No. 5). The progression begins before application of the tartrazine solution and ranges from 0.2 seconds to 60 seconds later. Scale bar represents 5 mm.

Guosong Hong/Stanford University

The researchers tested different concentrations of the dye on “scattering phantoms” (rectangular samples that mimic the optical distribution of human tissue) and slices of raw chicken breast. They then gently massaged the dye into the skin of anesthetized mice, where it was absorbed like a “facial cream,” Oh says. Within 10 minutes, the team began to see internal features beneath the top layer of tissue under visible light. Rubbing tartrazine into the animals’ stomachs revealed digestive activity, and spreading it on one of their legs exposed muscle. Using high-resolution laser imaging, the scientists saw details of nerves in the gastric system, tiny units in muscles called sarcomeres, and even the structure of blood vessels in the brain when the dye was applied to the mice’s scalps. If the tartrazine wasn’t washed off, the effect lasted for about 10 to 20 minutes, after which the skin returned to its original state.

Still images from the real-time video show the optical transparency of the mouse abdomen, allowing visualization of the animal’s abdominal organs. Scale bar represents 5 mm.

“Achieving Optical Transparency in Living Animals Using Absorbing Molecules,” by Zihao Ou et al. ScienceVolume 385. Published online September 5, 2024.

Previous work to make skin transparent has focused on introducing materials that are already transparent, such as glycerol or fructose solutions. These molecules could also reduce light scattering, but “they weren’t as efficient (as tartrazine) because they weren’t ‘colored’ enough,” says Guosong Hong, a materials science engineer at Stanford University and senior author of the new paper. Other approaches, which remove essential molecules in tissues rather than adding new ones, achieve a similar effect but can only be performed on non-living or biopsied tissues. For example, dermatologist Rajan Kulkarni of Oregon Health & Science University worked on an optical tissue clearing project in 2014, where researchers completely dissolved lipids from whole organs and animals and replaced them with a transparent hydrogel. “That was always a limitation, and we needed to change something,” he says. In vitro“If you don’t remove the tissues and organs, the organism itself would not be viable,” said Kulkarni, who was not involved in the new study. “This method is interesting because it allows us to make the skin, or epidermal layer, of a living animal transparent and visualize what’s underneath.”

Though it’s a long way from human trials, the concept could one day find medical applications. Hong suggests that it could help detect skin cancer early and make tattoo removal with lasers easier. It could also make veins easier to see, allowing blood draws and fluids to be administered with a needle, especially in older patients whose veins are harder to locate. In some cases, such a strategy could be a more attractive option than using imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound. “I think this technology will definitely be useful for visualization experiments in mice and other animals because you can visualize at the resolution of an optical microscope, whereas other methods like MRI, CT (computed tomography) and ultrasound don’t allow you to resolve that fine,” Kulkarni says. “In terms of proof of concept, it’s really cool. We don’t know yet clinically.”

The researchers found no adverse side effects in the mice after removing the dye. But Ou says that tartrazine and similar, more efficient molecules need to be further tested for safety in humans. Tartrazine can cause allergic reactions. And while the dye is FDA-approved, the agency strictly limits the amount it can be used in products. In the study, mice were able to tolerate the highest concentration used, 0.6 molar, for the short test period. But “human skin is about 10 times thicker than mice, which means the time needed for diffusion is probably much longer, from a few minutes in mice to hundreds of minutes in humans,” Ou says. “We hope that this initial study will spur further research to propose new molecules that are more efficient and safer for application in humans.”