Scientists warn that these pathogens could spark the next pandemic

Scientists have identified more than 30 pathogens that could cause the next human pandemic.

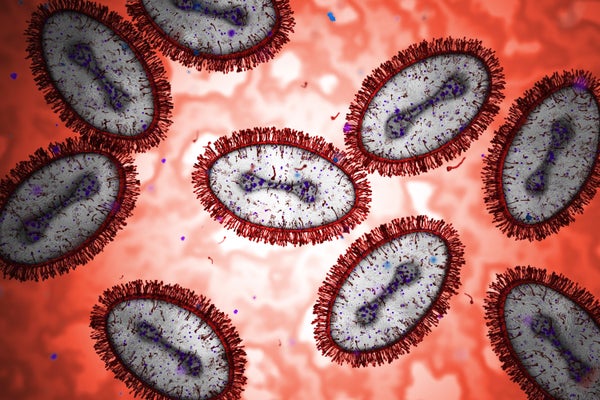

Monkeypox virus has been added to the WHO’s list of priority pathogens.

The number of pathogens that could cause the next pandemic has grown to more than 30, including influenza A, dengue, and monkeypox, according to an updated list released last week by the World Health Organization. Researchers say the list of “priority pathogens” will help organizations decide where to focus their efforts in developing treatments, vaccines, and diagnostics.

“It’s very comprehensive,” says Neelika Malavidge, an immunologist at the University of Sri Jayawardenepura in Colombo, Sri Lanka, who worked on the effort and studies viruses in the Flaviviridae family, which includes the virus that causes dengue fever.

The priority pathogens announced in the July 30 report were selected because they have the potential to cause a global public health emergency for humanity, such as a pandemic, based on evidence showing that the pathogens are highly contagious and virulent, and have limited access to vaccines and treatments. WHO identified about a dozen priority pathogens in 2017 and 2018.

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

“The prioritization process will help identify critical knowledge gaps that need to be addressed urgently and ensure the efficient use of resources,” said Ana Maria Henao Restrepo, who leads the WHO’s Epidemic Research and Development Blueprint team that produced the report.

Maravisi says it’s important to regularly review these lists to take into account major global changes, such as deforestation, urbanization and international travel due to climate change.

Recent efforts have identified and expanded the scope of dangerous pathogens across entire families of viruses and bacteria.

Chickenpox and smallpox

More than 200 scientists spent nearly two years evaluating the evidence on 1,652 pathogens – mostly viruses but also some bacteria – to decide which ones to include on the list.

Among the more than 30 priority pathogens is a group called coronaviruses. SarbecovirusesThis includes SARS-CoV-2, the virus that caused the global COVID-19 pandemic. MelbecovirusThis includes the virus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Previous lists included the specific viruses that cause Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and MERS, but did not include the entire subgenera to which they belong.

Other viruses added to the list include the monkeypox virus, which caused a global epidemic in 2022 and continues to spread in parts of Central Africa. The virus is considered a priority, as is its relative, the variola virus, which causes smallpox, despite being eradicated in 1980. This is because people are no longer routinely vaccinated against the virus and have not developed immunity, meaning that an unplanned release of the virus could cause a pandemic. The virus could also be used “by terrorists as a biological weapon,” Maravige said.

Half a dozen influenza A viruses have also been added to the list, including the H5 subtype that caused an outbreak among cattle in the U.S. The five new bacterial strains include those that cause cholera, plague, dysentery, diarrhea and pneumonia.

Two rodent-borne viruses were also added to the list because they have been shown to transmit sporadically from person to person. Climate change and increased urbanization may increase the risk of these viruses jumping to humans, the report said. The bat-borne Nipah virus remains on the list because it is deadly, highly contagious to animals, and there is currently no treatment to prevent it.

Many of the priority pathogens are currently confined to specific regions but have the potential to spread globally, says Naomi Forrester-Soto, a virologist at the Pirbright Institute near Woking, England, who worked on the analysis. She studies the Togavirus family, which includes the virus that causes chikungunya. “There’s really no place that’s most at risk,” she says.

“Prototype” pathogens

In addition to the list of priority pathogens, the researchers also compiled a separate list of “prototype pathogens” that can be used as model species for basic science research and for developing treatments and vaccines. “This could potentially accelerate research into less well-studied viruses and bacteria,” Forrester-Soto says.

For example, before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were no human vaccines for any coronavirus, says Malik Peiris, a virologist at the University of Hong Kong and part of the Coronavirus Family Research Group. Developing a vaccine against a family member would give the scientific community confidence that it would be in a better position to deal with any major public health emergencies from these viruses, he says. This also applies to treatments, he says, because “many antiviral drugs work against the whole group of viruses.”

Forrester Soto says the list of pathogens is reasonable given what researchers know about viruses. But “some of the pathogens on the list may never cause an epidemic, and some we haven’t thought of may become important in the future,” she says. “We’ve rarely predicted what pathogen will emerge next.”

This article is reprinted with permission. First Edition August 2, 2024.