December 6, 2024

3 minimum read

Wuhan virologist says there are no close relatives of the new coronavirus in his lab

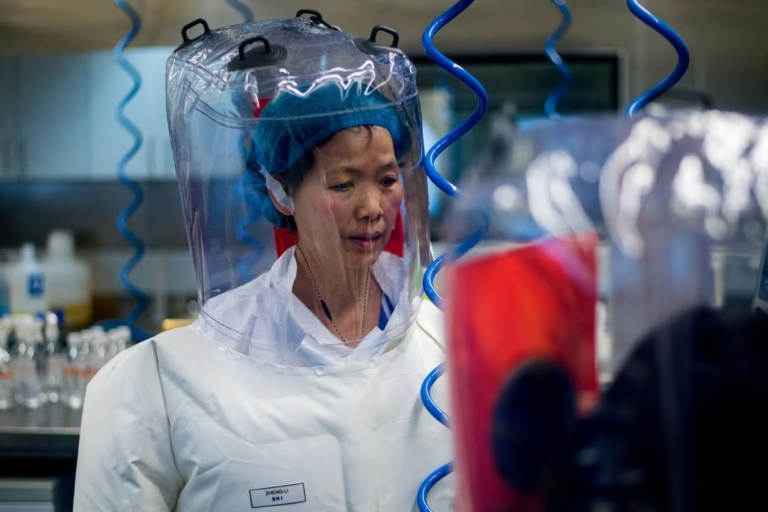

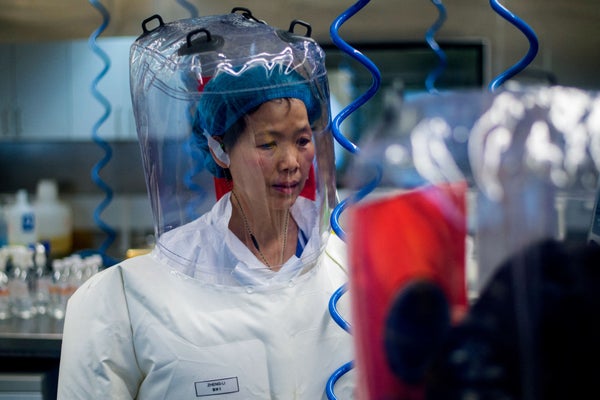

Virologist Shi Zhengli, the central figure in the novel coronavirus laboratory leak theory, reveals the coronavirus sequence from the Wuhan laboratory

Chinese virologist Shi Zhengli presented evidence that his lab has not conducted research on relatives of SARS-CoV-2.

Johannes Eisel/AFP via Getty Images

Rumors have been circulating for years that the virus that causes COVID-19 escaped from a Chinese lab, but the virologist at the center of the claim has discovered that the virus that causes COVID-19 was collected from bats in southern China. It presented data on dozens of new coronaviruses. At a conference in Japan this week, bat coronavirus expert Shi Zhengli reported that none of the viruses stored in her freezer are the most recent ancestors of the virus SARS-CoV-2.

Shi was leading coronavirus research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), a high-level biosafety laboratory, when the first coronavirus cases were reported in Wuhan. Soon after, theories emerged that the virus had leaked from WIV, either accidentally or intentionally.

Shi has consistently said that SARS-CoV-2 has never been seen or studied in her lab. But some commentators continue to ask whether one of the many bat coronaviruses her team collected in southern China over decades is closely related to bat coronaviruses. Mr. Shi has vowed to sequence the coronavirus genome and make the data public.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

The latest analysis, which has not been peer-reviewed, includes full-genome data and some partial sequence data for 56 novel betacoronaviruses, the broad group to which SARS-CoV-2 belongs. All viruses were collected between 2004 and 2021.

“We found no new sequences more closely related to SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2,” Shi said in a pre-recorded presentation at the conference, “Preparing for the Next Pandemic: Evolution, Pathogenesis.” Ta. and Virology of Coronaviruses, in Awaji, Japan on December 4th. Earlier this year, Shi transferred from WIV to the newly established National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Guangzhou Research Institute.

The results support her contention that there were no bat-derived sequences of viruses at the WIV laboratory that were more closely related to SARS-CoV-2 than those already described in the scientific literature. said Jonathan Pekar, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Wisconsin. Edinburgh, UK. “This confirms what she was saying, which is that she didn’t have anything very closely related, as we’ve seen over the years since then,” he said. say.

The closest known viruses to SARS-CoV-2 were found in bats in Laos and southern China’s Yunnan province, but they have diverged from a common ancestor with the virus that causes COVID-19. Years, if not decades, have passed since then. “She basically discovered a lot of what we expected,” says Leo Poon, a virologist at the University of Hong Kong.

long-term collaboration

For decades, Shi worked with Peter Daszak, president of the New York City-based nonprofit EcoHealth Alliance, to study coronaviruses in bats in southern China and their risks to humans. The research was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Agency for International Development, but in May of this year, the government denied federal funding to EcoHealth for failing to adequately oversee research activities at WIV. The provision has been stopped. These activities included modifying a coronavirus associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) to study the potential origins of this type of virus in bats.

Over the years, Shi and Daszak have collected more than 15,000 swabs from bats in the region. The team tested them for the coronavirus and rearranged the genomes of those that tested positive. This collection expands the diversity of known coronaviruses. “She discovered a sequence that could at least provide further context to our understanding of coronaviruses,” Pekar says.

In a large-scale analysis of 233 sequences, including new and previously published sequences, Shi et al. found seven widespread lineages and evidence of viruses that extensively exchange chunks of RNA, a process known as recombination. has been identified. Daszak said the analysis will also assess the risk of these viruses jumping between people and identify potential drug targets. “Information of direct value to public health.”

Daszak said the team has experienced delays in submitting research for peer review due to funding cuts, the challenges of working across regions, and multiple U.S. government investigations into ecohealth. However, the researchers plan to submit their analysis to a journal in the coming weeks.

This article is reprinted with permission. first published December 6, 2024.