Seventh person ‘cured’ of HIV by stem cell transplant

A German man was freed from HIV infection after receiving stem cells that were not resistant to the virus.

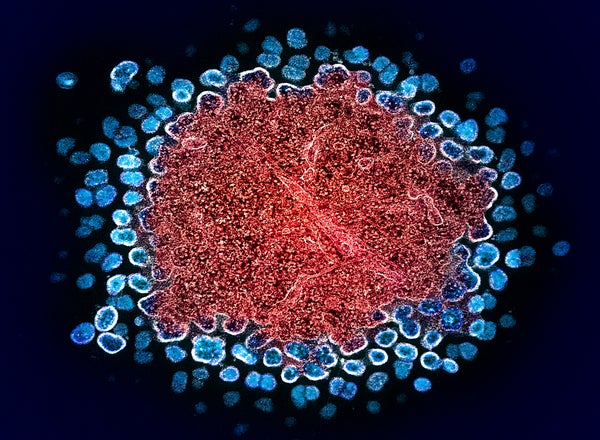

Color transmission electron micrograph of numerous HIV-1 virus particles (Blue) replicates in a fraction of chronically infected H9 T cells (red(Image courtesy of NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF), Fort Detrick, Maryland).

A 60-year-old German man has become at least the seventh HIV-positive person declared HIV-free after undergoing a stem cell transplant, but the man, who has been virus-free for nearly six years, is only the second person to have received stem cells that are not resistant to the virus.

“We were very surprised that the treatment worked,” says Ravindra Gupta, a microbiologist at the University of Cambridge in the UK who led the team that treated the other patient, who is now HIV-free. “This is a big deal.”

Timothy Ray Brown, known as the Berlin patient, was the first person to be found to be HIV-free after undergoing a bone marrow transplant to treat blood cancer. Brown and several others were transplanted with special donor stem cells. These stem cells had a mutation in the gene that codes for a receptor called CCR5, which most HIV virus strains use to enter immune cells. To many scientists, these cases suggested that CCR5 was the perfect target for HIV treatment.

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

The latest case, presented this week at the 25th International AIDS Conference in Munich, Germany, turns that around: the patient, known as “the next Berlin patient,” received stem cells from a donor who carried only one copy of the mutated gene, meaning that his cells expressed CCR5, but at a lower-than-normal level.

The case sends a clear message that finding a cure for HIV “is not just about CCR5,” says infectious disease specialist Sharon Lewin, director of the Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia.

Ultimately, the discovery could expand the donor pool for stem cell transplants, a risky treatment offered to leukemia patients but likely not available to most people with HIV. About 1% of people of European ancestry CCR5 It’s a gene, but about 10% of people with such ancestry have one mutated copy.

The case “broadens the horizon” for possible HIV treatments, said Sarah Waibel, a physician-scientist who studies HIV at the University of California, San Diego. About 40 million people worldwide are infected with HIV.

6 years HIV free

The next patient, from Berlin, was diagnosed with HIV in 2009. He developed a cancer of the blood and bone marrow called acute myeloid leukemia in 2015. His doctors were unable to find a compatible stem cell donor who carried the mutation in both copies. CCR5 The gene was mutated, but a female donor with one similar mutated copy was found, and the next patient in Berlin underwent a stem cell transplant in 2015.

“The cancer treatment was very successful,” says Christian Gaebler, a physician-scientist and immunologist at the University of Berlin’s Medical School, who published the study. Within a month, the patient’s bone marrow stem cells had replaced those of the donor. The patient stopped taking antiretroviral drugs that suppress HIV in 2018. And now, almost six years later, the researchers have been unable to find evidence of HIV replicating in the patient.

Shrinking reservoir

Previous attempts to transplant stem cells from donors on a regular basis CCR5 Genetic analysis has confirmed that in all but one HIV-positive person, the virus reemerges weeks to months after they stop taking antiretroviral therapy. In 2023, HIV researcher Asier Sáez-Sillion of the Institut Pasteur in Paris published data on an individual known as the Geneva patient, who hadn’t taken antiretroviral therapy for 18 months. According to Sáez-Sillion, the patient remains virus-free about 32 months later.

Researchers are now trying to understand why these two transplants were successful while others failed.

They propose several mechanisms. First, antiretroviral treatment significantly reduces the amount of virus in the body. Then chemotherapy before stem cell transplant kills many of the host’s immune cells where residual HIV lurks. The transplanted donor cells could see the remaining host cells as foreign and destroy them along with the virus lurking there. Rapid and complete replacement of the host’s bone marrow stem cells with donor stem cells could also contribute to rapid eradication. “If we can shrink the reservoir enough, we can cure people,” says Lewin.

Both the next Berlin patient and his stem cell donor CCR5 The mutated gene copies may have created an additional barrier that stops the virus from entering cells, Gaebler said.

Lewin said the case also has implications for treatments currently in the early stages of clinical trials that use CRISPR-Cas9 and other gene-editing techniques to cut out the CCR5 receptor from a person’s own cells. Even if these treatments can’t reach every cell, they could still be effective, Lewin said.

This article is reprinted with permission. First Edition July 26, 2024.