The Komodo dragon’s nightmarish iron teeth are a first for a reptile

It has long been thought that reptiles have simple, cheap teeth because they grow back regularly. But that’s not the case for Komodo dragons.

An adult Komodo dragon seen at the zoo.

Jürgen & Christine Sohns/imageBROKER.com GmbH & Co. KG/Alamy Stock Photo

There aren’t many scenarios that would end well if you were to peer closely at a Komodo dragon’s set of teeth. The giant lizard’s mouth is filled with 60 serrated teeth, each up to an inch long, that it replaces throughout its life, and from each dangle the remains of its previous meal, along with dozens of bacteria that feed on them.

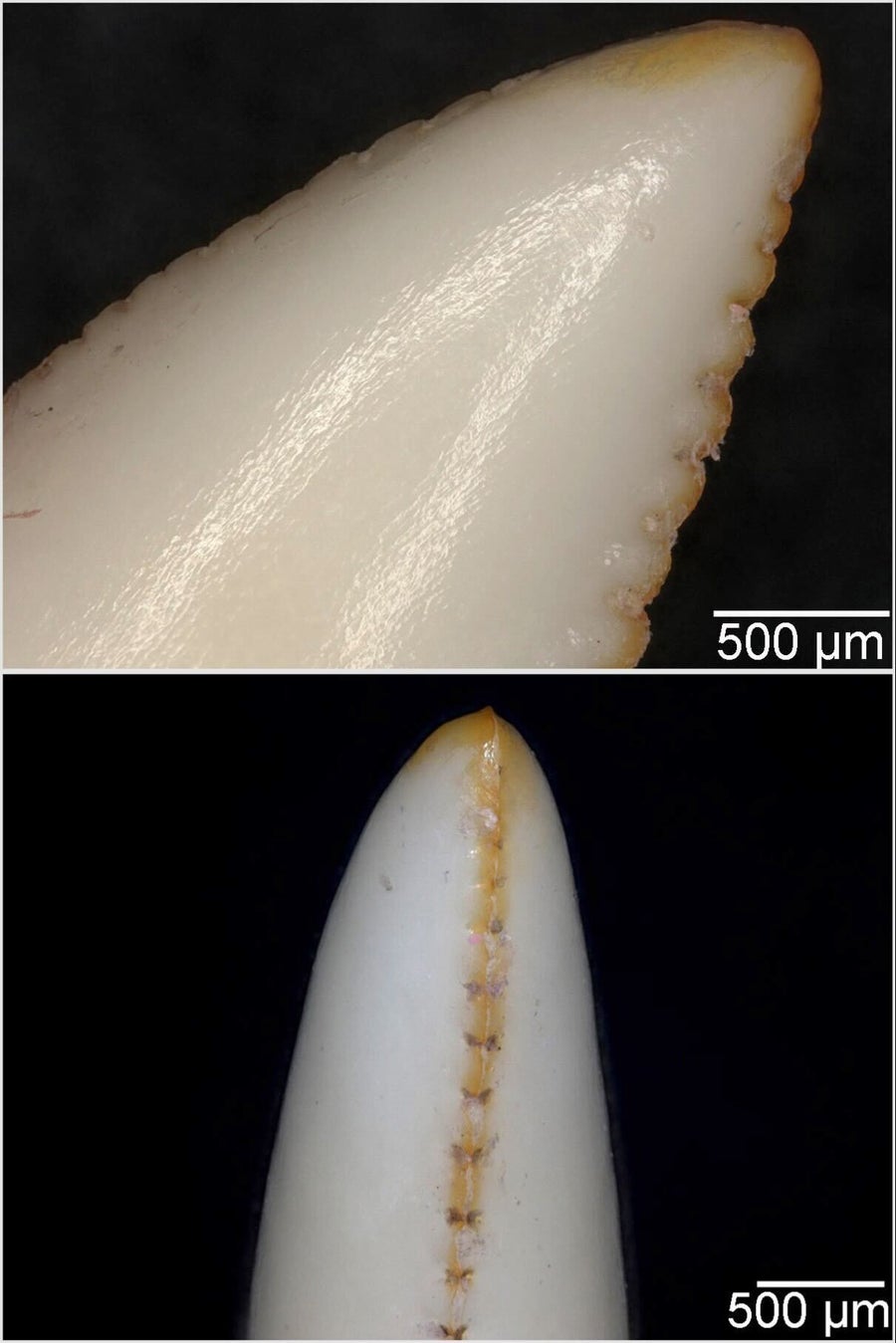

To be fair, paleontologist Aaron LeBlanc of King’s College London has studied the teeth of Komodo dragons after removing their grizzly markings and separating them from their rabid owners. His investigations have paid off: “Occasionally I would notice an orange-like discolouration on the outer layer of the tooth,” says LeBlanc. “I’ll be honest with you, I saw this three or four times and just dismissed it as feeding stains.”

But upon closer inspection, Leblanc found that the orange coloring he saw in the serrations and tips of Komodo dragons’ teeth was iron that was present before they bit into them, a finding described in a study published July 24 in the journal Nature. Natural Ecology and EvolutionThis is the first time that iron has been identified in a reptile’s teeth (iron is also known to be present in the teeth of some fish, salamanders, and a few mammals, including beavers).

Support science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

Reptile teeth have long been thought of as simple and inexpensive, because they grow quickly and are replaced multiple times throughout their owner’s lifetime. But studies like the new paper are changing that perception. “We’re just starting to scratch the surface of how complex reptile teeth actually are,” says Kerstin Brink, a paleontologist at the University of Manitoba who studies teeth but was not involved in the new study. “We’re really starting to look closely at different reptiles and are discovering all these really incredible adaptations.”

A close-up image showing the orange serrations running down the front and back of a Komodo dragon’s teeth.

“Ferrous-plated Komodo dragon teeth and complex dental enamel in carnivorous reptiles,” by ARH LeBlanc et al., Nature Ecology & Evolution, published online July 24, 2024

Komodo dragons, which live on several Indonesian islands and can grow up to 10 feet long, are typical reptiles when it comes to replacing their teeth, LeBlanc says. “They’re basically tooth factories,” he adds. The pointed tips of the teeth curve into the animal’s mouth, allowing it to tear off and swallow large chunks of meat. And the iron reinforcements are strategic, LeBlanc says. Orange detailing pinpoints a single serrated line running down the front and back of each tooth (the serrations are more pronounced on the back), marking the tips of the teeth as they alternate between stabbing, pulling, and swallowing.

LeBlanc was drawn to the giant lizard’s teeth because their sharp, curvaceous contours match the smiles of even more fearsome animals: dinosaurs. Such comparisons are a valuable approach for paleontologists, Brink points out. “When we study fossils, we have to look to modern analogues, especially when we’re trying to interpret behaviors that we can no longer observe once the animals are dead,” she says.

Inspired by the Komodo dragon’s discovery, Leblanc and his colleagues looked for similar signs of iron enrichment in the teeth of other modern reptiles and dinosaurs. They found that several species of monitor lizards had made the adaptation, albeit to a lesser extent, and that some crocodilians also had traces of iron in their teeth. As for the dinosaur teeth, the team found iron throughout, but thinks it was likely deposited during fossilization, given the abundance of iron on the Earth’s surface. “Iron in fossil reptile teeth might be the most unpleasant thing,” Leblanc says. “If you leave dinosaur teeth buried in the ground for tens of millions of years, the iron will eventually seep into every nook and cranny.”

Still, LeBlanc and Brinks agree that the study suggests scientists should take a closer look at the teeth of modern reptiles and dinosaurs alike, and be on the lookout for unexpected dental adaptations like those of the Komodo dragon. “We shouldn’t underestimate how complex reptile teeth are,” LeBlanc says.