December 19, 2024

4 minimum read

Trump’s selection as NIH director could have a negative impact on science and people’s health

Donald Trump’s selection of Jay Bhattacharya, a scientist critical of coronavirus policy, to the NIH is the wrong move for science and public health as the possibility of an avian influenza outbreak looms

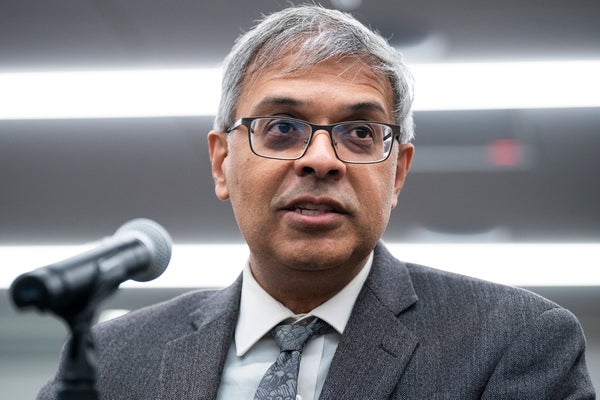

Jay Bhattacharyya spoke during a roundtable discussion with members of the House Freedom Caucus on the COVID-19 pandemic on Thursday, November 10, 2022, at the Heritage Foundation.

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc (via Getty Images)

President-elect Donald Trump wants Stanford University physician-scientist and economist Jay Bhattacharyya to lead the National Institutes of Health. NIH is a global scientific powerhouse. Its mission is to “explore fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and apply that knowledge to improve health, extend lifespan, and reduce disease and disability.”

Most politicians, even when criticizing the agency, recognize the agency’s contributions to building effective public health responses. For example, cancer mortality rates continue to decline thanks to the work that NIH researchers have focused on prevention, detection, and treatment.

Bhattacharyya doesn’t see the agency’s success that way. on his podcast Science from the peripheryMs. Bhattacharyya said she has recently been surprised by the “authoritarian trends in public health.” He echoed similar themes in an interview with Newsmax, saying, “We need to transform the NIH from being about controlling society to being about discovering the truth to improve the health of Americans.” .

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

Scientists who apply for NIH funding, sit on peer review committees, and manage grants may be surprised to hear that they control society. They’re doing science. Authoritarian claims are a sift to advance specific agendas that could damage the NIH. Bhattacharya’s scientific agenda is political, expressing concerns for individual autonomy against evidence-based public health science. This is unbecoming of a leader of the NIH.

Mr. Bhattacharyya has never explained how the NIH controls society, given its role as a research institution, perhaps setting research priorities and conducting research based on expert review. It’s hard to see how the NIH has any control other than giving money. Does he oppose public health laws that regulate lead emissions from cars, require vaccinations for children attending public schools, and promote folic acid fortification of bread and fluoridation of drinking water? This law has improved the nation’s health in terms of cognitive ability, infectious disease burden, neural tube defects during pregnancy, and oral health. Is this the kind of control he fears?

Public health authorities use science to decide on health promotion measures for the population, often vulnerable and unaware of the health risks, when the health benefits are clear. The NIH study provides evidence for these public health measures. While it is fair to debate the quality of scientific evidence and the benefits to population health compared to limitations on autonomy and choice, establishing mechanisms of population health risk and making recommendations based on this evidence is not fair. is not authoritarian and it is inappropriate to make such a comparison. Either to do good science or to build trust.

Mr. Bhattacharyya’s views are another unfortunate legacy of the coronavirus pandemic, when he opposed what he called public health overreach in the Great Barrington Declaration in 2020. The declaration states that isolating only those most at risk and allowing the coronavirus to continue spreading among healthier populations will achieve herd immunity without significantly increasing the mortality rate from the coronavirus. Build. In response, public health officials and NIH leaders criticized Mr. Bhattacharya on the basis of science. In the context of asymptomatic viral transmission, high transmissibility, and unavoidable population mixing, such “intensive protection” strategies are unlikely to protect vulnerable populations. Mr. Bhattacharya called this censorship and unsuccessfully tried to persuade the Supreme Court to act against social media platforms that have taken down his messages.

This personal outrage is a distraction and must not obscure the core of U.S. public health policy during the pandemic. Science supported school closures, work-from-home policies, limits on large gatherings in public places, and mask mandates as effective ways to slow hospital surges and buy time for vaccine development. You can try your hand at science, as many people do. But using science for policy is not authoritarian. Similarly, you may value personal autonomy and resist vaccination or mask-wearing mandates, as President Trump falsely claims to justify his candidacy. , the use of scientific evidence to support these measures does not mean that the scientists “engaged in censorship, data manipulation, or misinformation.” .

Authoritarianism in science and public health was not responsible for the pandemic’s heavy toll in the U.S. Structural factors such as income inequality and access to health care were key drivers of coronavirus mortality. As director of the NIH, I would be far more effective at preparing the nation for the next pandemic by investing in pandemic preparedness and infectious disease research, as well as ensuring universal access to health care.

Indeed, remedies have been proposed to make science less authoritarian, such as transferring NIH grant funding to states in the form of “block” grants (recommended by the conservative policy agenda Project 2025). Although it would not promote “non-authoritarian” public health, it would almost certainly have an effect. Degrading the quality of American science. Can states match the NIH peer review system, which is recognized worldwide as a model for transparent, confidential, and fair evaluation based on merit and scientific consensus? It is hard to imagine how decentralized state-level efforts could produce fairer reviews or more impactful science. For example, will scientists in some states be barred from funding research into family planning and women’s health?

It is unclear what other policies Mr. Bhattacharya will propose. Ban viral gain-of-function research? Eliminate research involving fetal tissue and limit research using animal models? As proposed by RFK Jr., President Trump’s nominee to head the Department of Health and Human Services. Is it to shift funding away from infectious disease research? Will peer review committees become less influential in determining scientific merit?

If that is a concern, the best way to “depoliticize science” is to get out of the way and allow scientific inquiry to drive research and peer review to determine funding priorities. That’s it. The “authoritarianism” that Bhattacharya denounces is often nothing more than the application of science to improve people’s health. Placing personal autonomy against the application of science to policy is fine for vanity webcasts and think tanks, but it’s inappropriate for NIH leadership. If he wants to focus on promoting individual autonomy in pandemic policy, he’s probably appointed to the wrong agency. Bhattacharyya is not the person the NIH needs.

This is an opinion and analysis article and the views expressed by the author are not necessarily those of the author. scientific american.