Since the first bird flu outbreak hit the United States earlier this year, health and agriculture experts have struggled to trace the patchy route of infection that spread the virus to herds of dairy cows and an unknown number of humans. Although the risk of infection still appears low for most people, dairy workers and others who have direct contact with dairy cows are becoming ill. Canada’s first human case reported, a teenager in critical condition. To better manage disturbing situations, scientists are turning to wastewater monitoring, a pathogen-hunting tool that has been powerful in the past.

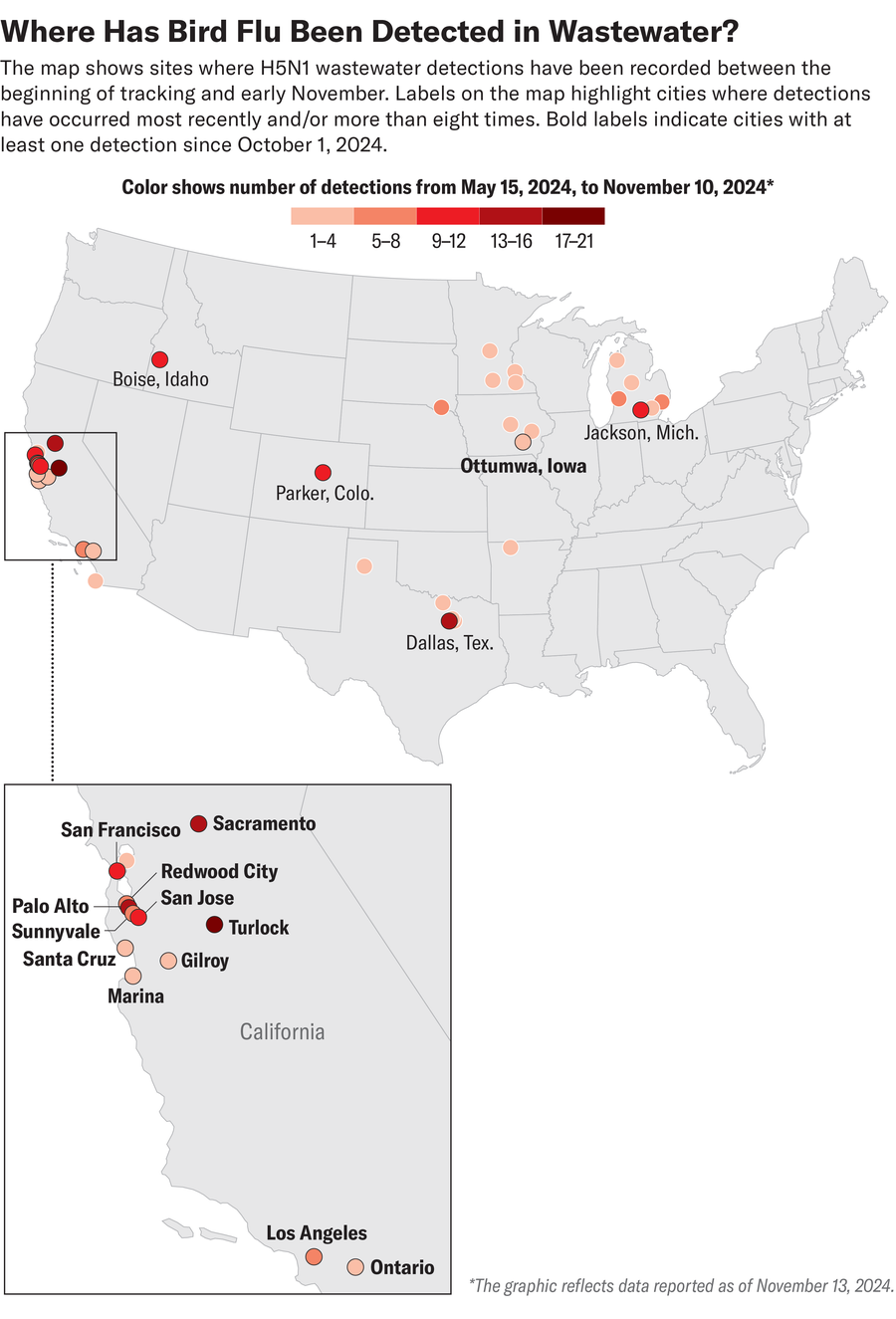

In the past few weeks, wastewater samples from several locations, primarily in California, including the cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento and San Jose, have tested positive for the genetic material of the H5N1 avian influenza virus. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Wastewater Surveillance System reported detections at 14 locations in California during a collection period that ended Nov. 2. As of November 13, 15 locations across the United States are being monitored by Stanford University and WastewaterSCAN, a project run by Stanford University. Researchers at Emory University reported positive samples this month. However, Alexandria Boehm, co-director of WastewaterSCAN and a civil and environmental engineer at Stanford University, said that finding H5N1 substances in wastewater does not necessarily mean there is a risk to human health. say.

Analyzing trace amounts of viral genetic material, often shed by feces in sewers, can alert scientists and public health experts to a potential increase in community transmission. For example, wastewater sampling is helping predict the number of coronavirus cases across the United States. However, the way H5N1 affects both animal and human populations complicates identifying the source of infection and understanding disease risk. H5N1 is potentially lethal in poultry. Although cows typically recover from symptoms such as fever, dehydration and reduced milk production, veterinarians and farmers report higher cow mortality rates in California than in other affected states. Masu. Cats that drink raw milk from infected cows can develop fatal neurological symptoms. Although the current human cases have not resulted in deaths (most people have flu-like symptoms, but some people have developed eye infections), past outbreaks outside the United States have resulted in deaths. It’s out.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

scientific american Boehm discusses the latest avian influenza detected in wastewater and how scientists are using these data to better track and understand disease spread and exposure in both animals and humans. We talked about dolphins.

(An edited transcript of the interview follows:)

When did WastewaterSCAN start tracking H5N1?

In Amarillo, Texas, we found very high levels of influenza A RNA (one of the four types of influenza viruses that infect humans) in wastewater after influenza season ended (spring 2024). I noticed something very unusual: nucleic acids were detected. This was amazing. Because we know that influenza A infections in sewers are occurring in the community. However, the number of cases in the community was not that high, as the flu season had passed. Then I heard that a cow infected with avian influenza had been found in the same area of Texas. So we worked with local wastewater treatment plants and public health officials to test wastewater. And indeed, it turned out that it was H5 (a subtype of the avian influenza A virus) in the waste. We determined that most of that H5 comes from legal discharges from milk processing plants to sanitary sewers.

H5 testing was then carried out nationally and H5 tests were found in areas where cattle were confirmed to be infected shortly thereafter. In fact, the CDC sent a memo to states in June asking them to attempt to measure H5 concentrations in wastewater, recognizing that measurements would help understand the scope and duration of the outbreak in the United States.

Was the wastewater analysis able to trace the source of the infection?

Although we cannot always exclude the possibility that wild birds, poultry, or humans are the source, the overall overwhelming evidence suggests that most of the inputs are likely to be from milk. That milk goes into consumers’ homes and people throw it down the drain. You’ve probably poured milk down the sink at some point. I’m sure I do too. It has also come from licensed operations that produce cheese, yogurt and ice cream, potentially starting with dairy products containing avian influenza nucleic acids.

I would like to emphasize that milk in people’s homes that may contain avian influenza RNA; do not have Infectious or a threat to human health. This is simply a marker that milk has entered the food chain, where the virus originally was. This bacteria is killed because dairy products are pasteurized. By the way, that’s why drinking raw milk and eating raw cheese is now less recommended. The RNA that makes up the genomes of these viruses is very stable in wastewater. Stable even after pasteurization. Therefore, even if raw milk is pasteurized, RNA will still be present at approximately the same concentration.

Its detection in wastewater does not mean there is a risk to human health. This means that there are still infected cattle in the vicinity and work is still needed to identify them and remove their products from the food chain, which is the goal of the officials responsible. . Trendy aspects.

How can we better determine where the virus’s genetic material comes from and assess its human infection rate?

This is very difficult because viruses are not genetically distinct (between sources). You can’t say, “Oh, this is what happens in humans, so let’s look for it.” We are working closely with public health departments who are actively working to sequence positive influenza cases. If (more) people start having this symptom, we’ll probably know because we’ll be able to tell a difference in our wastewater.

There is no need to worry at this time, as the risk of contracting H5N1 is very low and the symptoms are very mild. But I think one of the concerns is that the virus could mutate during the upcoming flu season. (Seasonal Influenza) People who are infected with H5N1 can also become infected, and new strains that can cause more severe illness may emerge. We hope that wastewater data, and all the other data that people and institutions are collecting, will help us understand what’s going on and better protect public health.

What trends are you seeing in surveillance today?

California just recently lit up. Many wastewater samples in California have also tested positive in highly urbanized locations such as the Bay Area and Los Angeles. The question is, why? In some of these places, there are actually small factories where people make dairy products using milk. But another explanation, as I mentioned earlier, is that it’s simply a waste of dairy products.

How do H5N1 levels in wastewater correlate with infectious diseases in animals?

We see this as an early or concurrent sign that nearby cattle are infected with avian influenza. The first detection was in Texas, and for a while there were also a lot of detections in Michigan, but the hotspot is now California. As scientists, we will analyze all this in the future. However, anecdotally, detection of H5 in wastewater continues once a swarm is identified and, once under some control, becomes undetectable.

Public health officials can use this data to say, “Okay, we got a positive test at this location. What are the different sources that could explain that? This sewage shed is providing dairy to industry. Have you tested all the cattle? Have you eliminated all the infected herds in the state now that the sewage is no longer positive?”

How else do scientists and officials track cases and spread?

(U.S. Department of Agriculture) and various organizations across the country are pursuing it from an animal health perspective and a food safety perspective. Therefore, herds and dairy products are tested. There is also testing of poultry, as well as testing of infected flocks and workers who have had contact with infected poultry. On the clinical side, there is a movement to sequence influenza-positive samples to understand the type of influenza, as a kind of safety net to see if bird flu may be circulating among people. there is. So far, cases have occurred in people who have had actual contact with infected animals, people who work on farms, and possibly some of their families.

How is tracking H5N1 different or similar to coronaviruses and other pathogens?

All of the other pathogens we are tracking are conceptually similar to the coronavirus, with humans being the source (of the pathogens in wastewater). The occurrence of viral or fungal substances in wastewater has been found to be consistent with the case. Bird flu is the first example of using wastewater to track something that, at least for now, is not primarily of human origin, but that can affect human health for a variety of reasons. This is a very good case study of how wastewater can be used to track not only human diseases but also zoonotic pathogens, i.e. pathogens that affect animals. So we are now thinking about what else we can use wastewater for. What other types of animal byproducts end up in the waste stream that may contain infectious disease biomarkers? H5 is our first example, and further I’m sure there are many examples.