November 27, 2024

4 minimum read

What is the difference between a drought in the eastern United States and a drought in the western United States?

Drought is synonymous with the western United States, but it can hit the eastern United States surprisingly quickly, too.

New Jersey’s Manasquan Reservoir, which provides drinking water to 1.2 million people, was less than half full by mid-November.

Lokman Vral Elibor/Anadolu (via Getty Images)

The water level in the reservoir is falling. Multiple wildfires have ignited dry brush in the crater, exposing people across the region to harmful air pollution levels. There has been very little rain in recent weeks.

This time we’re not talking about the frequently drought-prone western United States, but rather the typically wet western United States. eastern An unusually severe drought has caused water restrictions, crop damage and fires in six weeks, about the same amount New Jersey typically experiences in six months. While some of the effects are similar to those of the Western Dry Period, the Eastern Drought is a little different.

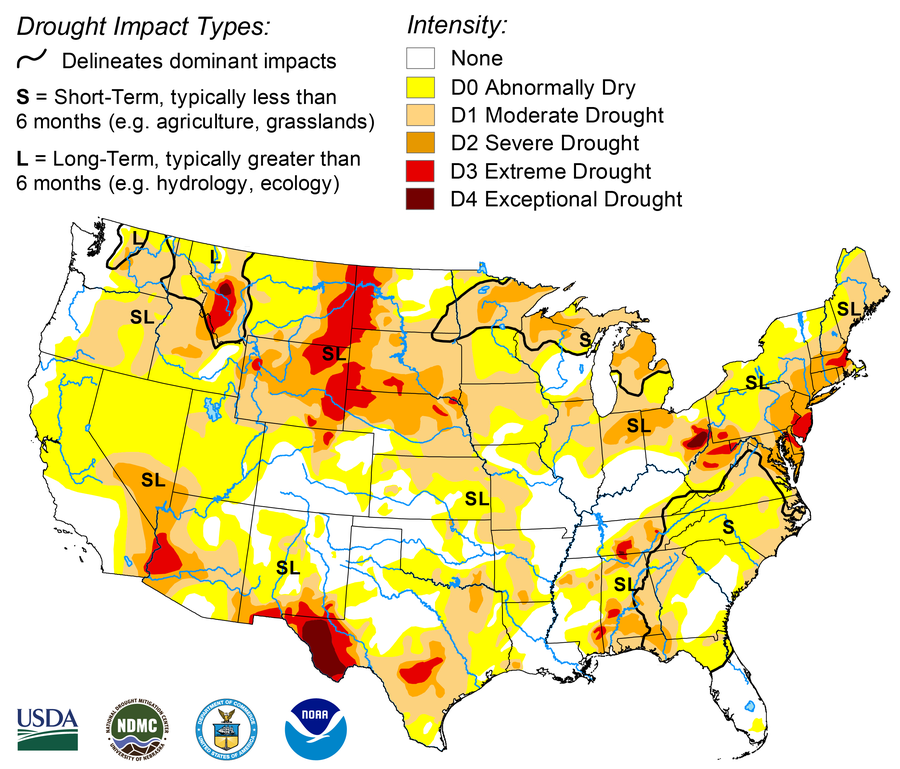

The two halves of this country have very different climates. Much of the West has distinct wet and dry seasons, with rain and snow falling from late fall to early spring for most of the year. As the snow on the tops of the high mountains of the West gradually melts throughout the spring and summer, when all is well, water replenishes streams and provides sufficient water for plants. But when winter precipitation is low and high spring and summer temperatures cause rapid snow melting, there is less volume to keep the reservoir filled. Western states are managing these resources in preparation for a dry year, but years of no rain and intense heat could lead to disastrous droughts. This happened 10 years ago in California. That’s when the heat wave officially pushed more than half of the state into “exceptional” drought conditions, the highest category used by the U.S. Drought Monitor.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

Most of the East Coast, on the other hand, sees rainfall every month of the year and usually does. Dry periods there “tend to be short-lived and don’t cause the catastrophes that they do in western North America,” said Benjamin Cook, a climate scientist who studies drought at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

The U.S. Drought Monitor is a collaboration of the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map provided by NDMC.

However, droughts can quickly develop after several weeks between storms. This fall is especially noticeable in the Tohoku region. After a very wet winter and spring, many regions experienced six weeks of little or no rain and unusually warm temperatures. And as temperatures rise, evaporation increases, causing the ground and plants to dry out even faster. “What’s surprising about the Northeast’s water resources is how far we’ve declined,” said David Bout, a hydrologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “All of these lakes and rivers are several feet lower than they should be.”

Wells are running dry in Connecticut. Philadelphia officials are closely monitoring the Delaware River’s “saline front” — where the river’s fresh water meets the ocean’s salt water — in case salt water pushes further up the river and threatens drinking water supplies. New York City has issued its first drought warning in 22 years, asking residents to take various steps to voluntarily reduce their water use. “It’s shocking to read this story because it’s not an issue that the Northeast typically deals with,” said Dennis Gutzmer, a drought impacts expert at the National Drought Mitigation Center.

It could even get worse. Southern New England experienced a record drought in the 1960s, after years of below-average rainfall. If the same situation were to happen now that population and infrastructure have increased significantly since then, “we would be in a really bad place,” Bout said. “Most places will either run out of water or it will be barely bearable.”

Current dry conditions on the East Coast also make fall wildfires even worse than normal. It ignites more easily and burns hotter and longer. “We’re used to some reliable rain, and that helps put out fires,” said Michael Gallagher, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service who studies wildfires. But this year, “fires continue to occur in increasingly atypical locations,” including Prospect Park in central Brooklyn and small green spaces in Manhattan.

One of the little things that keeps the drought from getting worse is that it happens in the fall. This is because both humans and plants require less water in the fall, and there is generally less evaporation than in the heat of summer. But seasonal timing also contributes to other exacerbating factors in wildfires. For example, deciduous trees shed their leaves, increasing the potential fuel for a spark.

Last week and this week, several storms brought light amounts of rain and snow to the region, suppressing the fires and reducing the risk of further fires. But they can’t end the drought. It will take some time for these rains to become sufficient to eliminate the current deficit. “One more storm isn’t going to make everything better again,” Gallagher said. Bout agreed, saying that “the soil is so dry” that it will probably take 10 inches of rain over the next few months for water levels to return to normal.

We don’t know exactly what the weather will be like for the rest of fall and winter. Reliable weather forecasts are only available for about seven days into the future, and seasonal forecasts only indicate the relative probabilities of what the weather will be like over the next few months. For the Northeast, warmer-than-average weather may be favored at this time, but the chances of it being wet or dry are about equal.

Looking further ahead, as the climate continues to change with rising temperatures, Bout et al.’s study shows that fluctuations between wet and dry seasons in the Northeast will occur more frequently, on the order of every two to four years. suggests that it is.

For the rest of the year, the wildfire risk should decrease at least a little as the days get shorter and the nights get colder. “It’s harder to burn when it’s really cold,” Gallagher says. This is especially true if the frost occurs at night, as the moisture in the frost takes time to evaporate before the sun comes up. However, Mr Gallagher warned that large-scale wildfires continue to occur in the Northeast in all seasons. Fire activity could resume if dry, windy weather patterns reestablish themselves.

And even if we get rain and snow in the coming months and the fire danger remains low, water tables, streams, rivers and lakes will have some “memory” and it will take time for them to recover. Boot says it will take a while. . “This situation will continue throughout the spring and summer,” he added.