September 24, 2024

5 Time required to read

How are Nobel Prizes distributed?

Nobel Prize co-recipients are not necessarily direct scientific collaborators, and the prize money is not necessarily shared equally.

Most scientists never get to win the Nobel Prize, arguably the most prestigious award in science: Only physicists, chemists, and specialists in physiology or medicine are eligible for the honor, which comes with a gold medal, a diploma and a cash prize currently worth up to 11 million Swedish kronor (about $1.07 million).

Billionaire Alfred Nobel established the prize system and categories in his will in 1895. He stipulated:

“(My capital) shall constitute a fund, the interest of which shall be distributed annually as prizes to those who, during the previous year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind. The interest shall be divided into five equal parts, to be distributed as follows: one to the person who shall have made the most important discovery or invention in the field of physics, one to the person who shall have made the most important discovery or improvement in chemistry, one to the person who shall have made the most important discovery in the field of physiology or medicine, one to the person who shall have produced the most outstanding work in an idealistic direction in the field of literature, and one to the person who shall have contributed most or been the most outstanding in promoting friendly relations between nations, in the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and in the establishment and promotion of peace congresses.

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

It seems simple: the first prizes in the sciences were awarded in 1901 to Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen (Physics), Jacobus H. van’t Hoff (Chemistry) and Emil von Behring (Physiology or Medicine).

However, the first Chemistry and Physics prizes were awarded for work going back further than the “previous year”: one related to work beginning in the 1870s, the other to work in 1895. Scientific American From 1901 to 2023, it was calculated that the average time between publication of a major study and a Nobel Prize nomination was 20 years, regardless of field. And in 1902, there were joint prize winners, when Hendrik A. Lorentz and Pieter Zeeman shared the Physics Prize for their work on magnetism and radiation.

The expansion of the Nobel Prize eligibility in his will was the result of a decree enacted by the Nobel Foundation and his heirs in 1898. Specifically,

The provision in the will that the prize be awarded each year for works “of the previous year” is to be understood as meaning that the prize would be awarded for the most recent achievements in the cultural fields mentioned in the will, and that older works would only be awarded if their importance had not become apparent until recently…

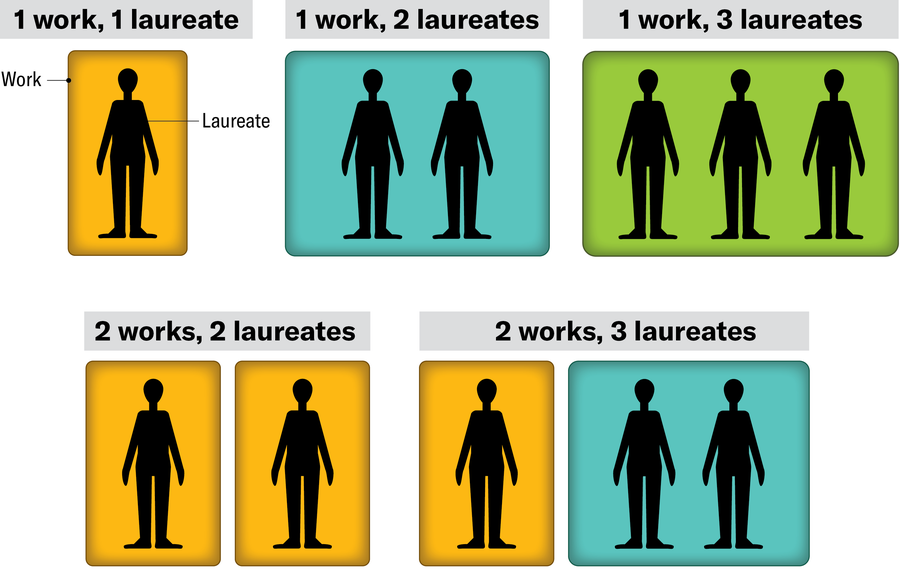

The prize money may be divided equally between two works each deemed worthy of the prize. If the work being awarded is created by two or three persons, the prize money will be awarded jointly to those persons. In no event may the prize money be divided among more than two persons.

The rules on timing are relatively clear. Simply put, award-eligible research need not be limited to the year prior to the award. But the rules on co-awardees are more complicated. What does this mean?

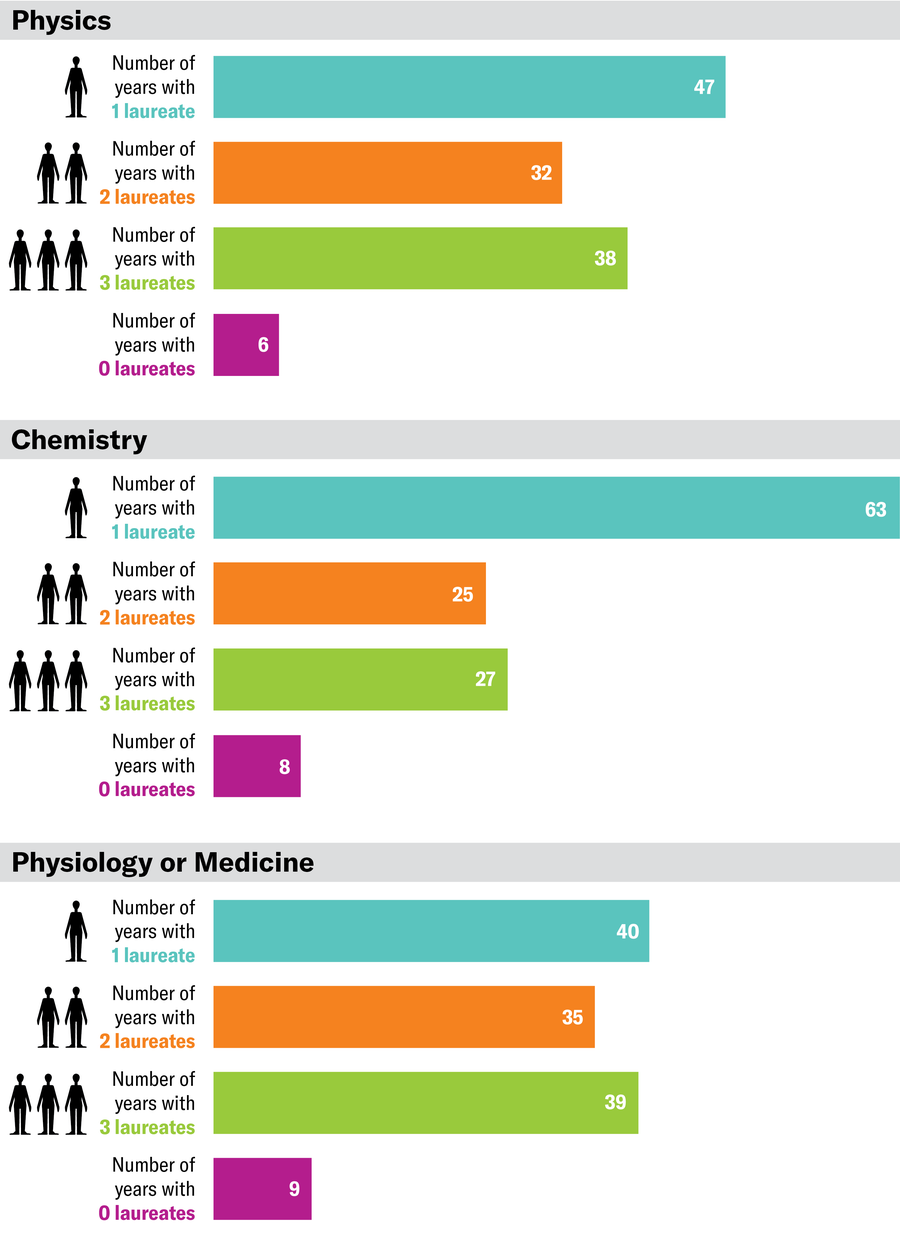

Up to three Laureates (also called Laureates) are awarded each year in the scientific fields of Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine. From 1901 to 2023, the breakdown is as follows:

But co-recipients are not necessarily direct collaborators. For example, James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo shared the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on proteins that inhibit the immune system and how those proteins can be manipulated to fight cancer. Although both men made important discoveries in the emerging field of cancer immunotherapy, they conducted parallel research in different laboratories, focusing on different mechanisms.

Many joint laureates were not contemporaries: for example, the 1986 Physics Prize was awarded to Ernst Ruska, Gerd Binnig, and Heinrich Rohrer for work completed 48 years apart: Ruska developed the first electron microscope in 1933, and Binnig and Rohrer developed the scanning tunneling microscope together in 1981.

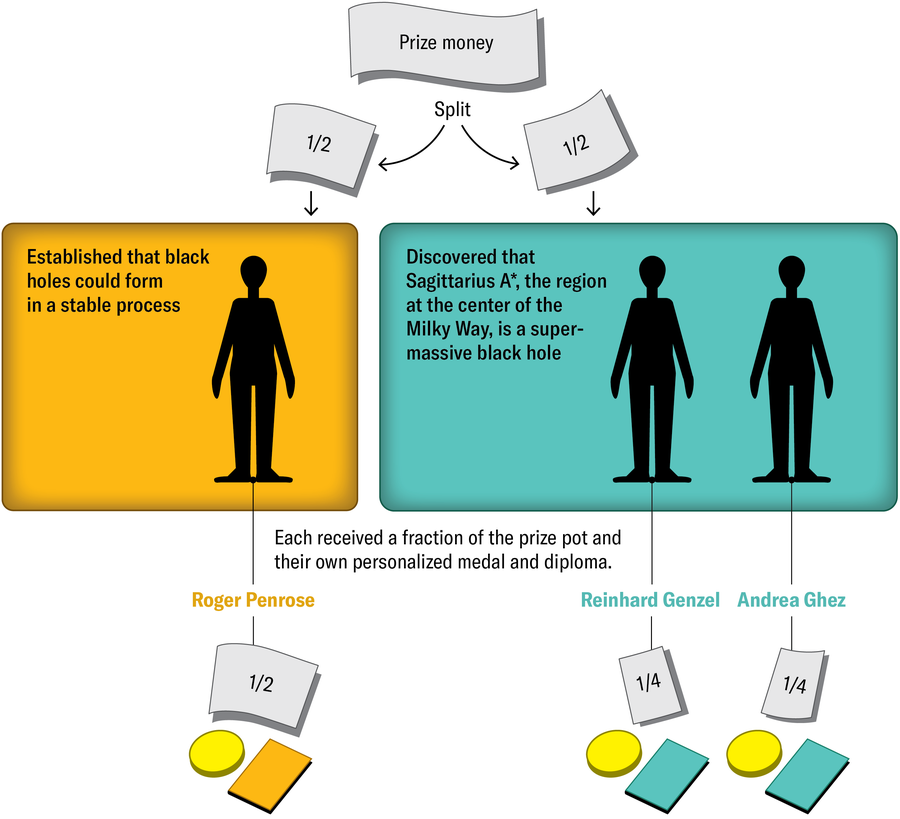

Each laureate receives a personal gold medal and a certificate, but the prize money is not necessarily shared equally among the co-recipients. This can be a bit confusing unless you shift the focus from the people who carried out the research to the research that is being celebrated.

According to the statute, “The prize money may be divided equally between two works each of which is deemed worthy of a prize.” Note the emphasis on “work.” In essence, it is the research that is being praised, not the researcher. Furthermore, the statute states that “If the work to be rewarded was created by two or three persons, the prize money shall be awarded jointly to the two or three persons. In no case may the prize money be divided among more than two persons.”

Overall, there are five possible scenarios:

Here’s how it played out in 2020: The Physics Prize was awarded to Roger Penrose, Reinhard Genzel, and Andrea Ghez. As the Nobel Foundation puts it, Penrose was lauded “for his discovery that the formation of black holes is a robust prediction of the theory of general relativity,” primarily due to his 1965 paper that established the physical basis of black holes. Genzel and Ghez were both lauded “for their discovery of a supermassive compact object at the center of our galaxy,” work carried out in parallel by separate teams about 25 years apart.

Half of the prize money was awarded to Penrose, and the other half was split between Genzel and Ghez.

Interestingly, the law does not strictly follow the wording of Nobel’s will, which focused on influential “persons” rather than “works.” Nearly 123 years after the first award ceremony, that tension still seems unresolved. The award committee continues to call for and popularize up to three awards. people Each year, a winner is selected in each category and a check is presented to each scientist. the workIn a world where the work that gets recognised is increasingly the product of many collaborators, the conflation of lead scientists with work by a large number of researchers is at the heart of many criticisms of the Nobel Prize (though there are other aspects that deserve criticism, such as the surprising lack of diversity among laureates).

Caroline Wagner, a science and technology scholar who focuses on international cooperation, wrote in 2017:

While experts have expanded the ways in which they evaluate contributions, prizes like the Nobel Prize have not kept up. The parts of scientific history taught in schools still focus on individual contributors like Marie Curie and Albert Einstein. The interdisciplinary collaborations that make up most of science today are even harder to explain and visualize…. The Nobel Prize, which was created to recognize 19th-century creativity, may no longer reflect true contributions in 21st-century science.

Still, many people, including myself, remain fascinated by the idea that a scientist can be blindsided by a phone call announcing a Nobel Prize win, turning an ordinary day into a remarkable one. And there’s something lovely about the frenzy of science communication that follows, giving us all an excuse to reflect together on influential research.