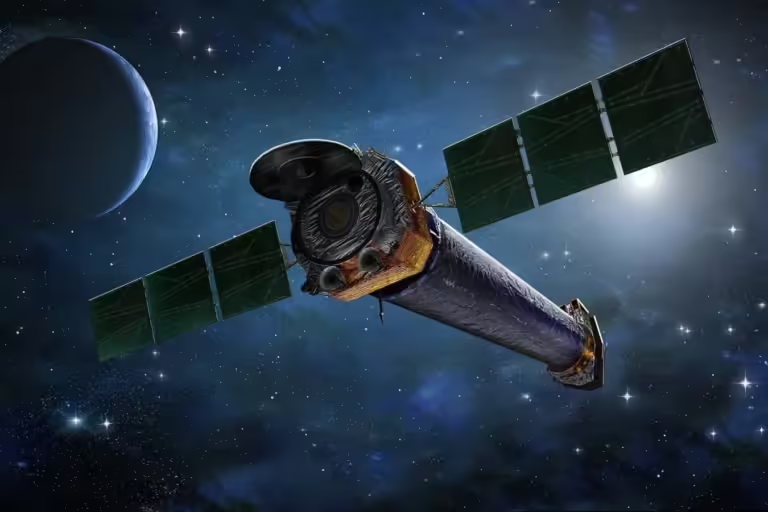

Chandra X-ray Observatory

NASA/CXC & J. Vaughan

On July 23, 1999, just a few months before I enrolled in college, NASA’s Space Shuttle Columbia launched with a precious cargo. Not only was it carrying a crew led by the first woman, Eileen Collins, its primary purpose was to launch a new flagship space telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Chandra was the heaviest payload ever carried by NASA’s Space Shuttle, and it would be one of the last two missions completed by Columbia before it tragically exploded after launch on February 1, 2003.

Chandra is the first, and so far only, NASA mission named after a person of color. The late theoretical astrophysicist and Nobel Prize winner Subramanian Chandrasekhar was called Chandra by his friends and family. Chandrasekhar, whose last name means “crown of the moon,” made many important contributions to astrophysics. His most important work was discovering the Chandrasekhar limit, the maximum mass a white dwarf remnant can have before it collapses into a black hole.

It’s fitting that an X-ray telescope mission should be named after a scientist who has spent his life thinking about the physics of black holes, as X-ray telescopes play a key role in black hole research. X-rays are high-energy light waves, which means they are produced in extremely energetic environments, such as those around black holes, where extreme distortions of space-time cause strong gravitational forces to accelerate particles to extremely high speeds. In other words, when we look at the universe through the lens of X-ray astronomy, rather than the visible wavelengths of traditional telescopes, we see an entirely different universe.

Importantly, X-ray astronomy can’t be done from the Earth’s surface, because it’s blocked by the Earth’s atmosphere. That’s good for human health, but not so good for astronomers. Chandra is therefore a reminder of just how important it is to keep low Earth orbit debris-free, so we can safely launch space telescopes that perform tasks that are simply beyond the control of the Earth.

I feel like I have grown up with Chandra. And not just because I attended college at Chandra headquarters, now known as the Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Massachusetts, and was often mistakenly called “Chandra”. One of my lab projects as an undergraduate was to adjust the light-gathering part of Chandra’s backup camera. The following year, I wrote my undergraduate thesis under the guidance of Martin Elvis, an expert in X-ray astronomy. My research focused on the particle winds that fly out of galaxies that contain supermassive black holes. I used Chandra data to analyze what structures these galaxies take. It is true that Martin’s letter helped me secure admission to at least one PhD program. In other words, without Chandra, my career may never have begun.

I’m one of thousands of scientists in the fields of physics and astronomy who can tell similar stories of how Chandra data formed the basis of the early stages of their careers, or how they dedicated their lives to using Chandra to explore the mysteries of the universe. Laura Lopez of Ohio State University has used Chandra to study supernovae for many years, as has Daniel Castro, now a staff scientist at CfA. The three of us served as postdoctoral researchers together at Massachusetts Technology and are part of a generation that grew up on the power of the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Now, after 25 years in orbit, Chandra is under threat, not because of the reality of space debris and aging equipment, but because of political climate. NASA’s top political appointees under US President Joe Biden recently explored scaling back the project, but the scientific community has been working with Congress to keep the mission alive. But things will never be the same. A compromise proposal, not yet signed into law, involves drastically reducing Chandra’s funding and limiting its scientific scope. There is no scientific justification for doing this, especially against the recommendations of expert advisors. Still, NASA has cut grants already promised to scientists, leaving doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers without the funding they could count on to cover their living expenses.

Chandra deserves better. And so does its global audience. Thanks to Chandra, we have discovered new neutron stars and learned about their interiors. Our knowledge of black holes has blossomed. We have gained a deeper understanding of stellar life cycles and the history of our galaxy. We have been able to study galaxy clusters and learn how dark matter is distributed within them, putting the Milky Way in context. There is still time to save Chandra, a monument to human ingenuity. The fact that it is still going strong after 25 years should be celebrated and it should be honoured by the continuation of the mission.

Chanda’s Week

What I’m Reading

My friend is Andrea Kindried. From Slavery to the Stars: A Personal Journey And it’s beautiful.

What I’m seeing

I’ve seen some classic episodes Star Trek: The Next Generation Like “Remember Me”.

What I’m working on

I am developing a new course that prepares students to understand science in a social context..

Chanda Prescod Weinstein is an associate professor of physics and astronomy and a faculty member of women’s studies at the University of New Hampshire. Her latest book is A Disordered Universe: A Journey into Dark Matter, Space-Time, and Dreams Deferred.

topic: