December 23, 2024

5 minimum read

A little math can streamline your holiday cookie making.

Making cookies takes time and effort. Here’s how to make this holiday season easier and less wasteful with a little math.

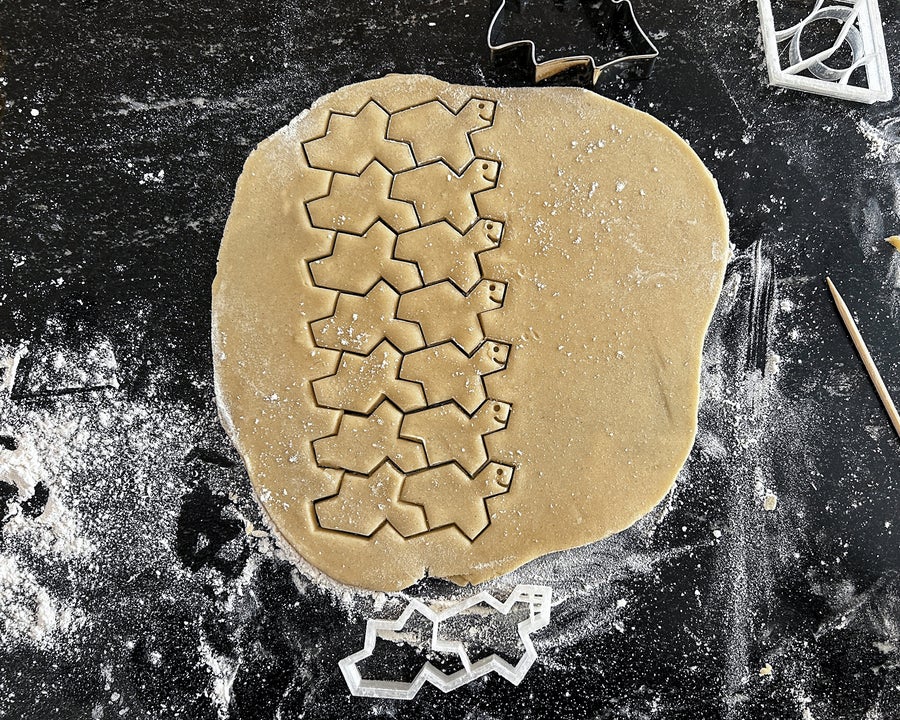

Using cookie cutters to create mosaic patterns saves time and allows you to use more dough.

When our kids were little, we spent a lot of time together in the kitchen. We took the opportunity to sneakily teach them about science such as heat and temperature, fluid flow, density, viscosity, physical changes, chemical reactions, acids and bases, and more. We explained how these properties combine to cause carbon dioxide to magically make cakes rise. We told them about yeast and other interesting microorganisms.

We also talked about mathematics such as weights and measures, area, and volume. Pizza is a great way to introduce fractions. We had fun baking cookies together and used different cookie cutters. My son loved dinosaurs, so not only did he have dinosaur cookie cutters, but he also had flowers, hearts, stars, animals, and more. An interesting challenge arose when using cookie cutters. With the cookie cutter, there were gaps between each of the shapes I cut out. I had to re-roll it to use up all the dough. But then it got warmer and I had to let it cool down before cutting it again. This took some time.

I needed a more efficient way to divide the dough.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

When you make cookies using traditional cookie cutters, you often end up with a lot of leftover dough.

Being a mathematician, I had heard about tiling and tessellation. This refers to the use of one or more geometric shapes to cover a surface without overlap or gaps. That was the answer to the cookie cutter problem.

So I looked for mosaic cookie cutters, but all I could find were squares and hexagons. These work, but aren’t particularly interesting as far as shape goes. Then, about 15 years ago, the first 3D printers arrived. It is now possible to make custom cookie cutters, and now all you have to do is choose the shape. Many shapes can be used for tessellation, including equilateral triangles, irregular triangles, rectangles, and irregular pentagons. Part of the irregular pentagon was discovered by the late amateur mathematician Marjorie Rice, who created an artistic and mathematical exhibition called “Mathemalchemy” with collaborators such as Duke University mathematician Ingrid Daubecise and textile artist Dominique Arman. You can see it in “. The exhibit also features a mosaic cookie cutter with the pi symbol, adapted appropriately by Daubechies.

There are other examples. Islamic art includes beautiful and creative designs that utilize the symmetry of the pentagon.

You have even more options when combining two or more shapes. For example, octagons and squares, pentagons and rhombuses, or all the great works of MC Escher. But not all make good cookies. I made a cookie cutter in the shape of an Escher lizard, but the leg broke when I cut the doll apart.

All these tessellations are periodic. That means there is a repeating pattern. In the 1970s, Roger Penrose proposed that darts can be aperiodic (meaning that all possible configurations are aperiodic) only if they follow local rules specifying which sides of the dart can touch each other. We discovered two shapes called kites and darts that can be lined up on a flat surface. However, if the rules are not followed, they will be tiled regularly. This is perfect for cookie cutters because you can place raw dough in regular rows and cookies on a regular or non-regular basis. More information about Penrose tiles can be found on the video channel Veritasium and on the web page titled “Penrose Islamic Interlacing Patterns.”

Mosaic cookie cutters in the shape of kites and darts, like this one, create lovely patterns and use more fabric than other shapes.

A few years ago, with a lot of help from some friends, I used a 3D printer to make kite-shaped cookie cutters and arranged the tiles in regular rows to play darts. After baking, the pieces can be arranged regularly or irregularly. This worked beautifully.

And then the hat arrived.

For about 50 years, mathematicians have wondered whether there might be a single figure that arranges planes nonperiodically. And in 2023, David Smith, Craig Kaplan, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, and Samuel Myers succeeded in discovering an elusive aperiodic monotile they called “Hat” or “Einstein.” did.

My first impulse was to make a cookie cutter in the shape of a hat. I found it very difficult to arrange the pieces so that there were no gaps or overlaps. However, as Craig Kaplan reports, the people who discovered the hat also realized that it could actually transform into an infinite number of aperiodic monotiles. Three of the monotiles can be arranged periodically and aperiodically and are perfect as cookie cutters.

The chevrons, which Smith and his staff called “tiles (0,1),” are easy to make, easy to use in dough, and the baked cookies are arranged in beautiful patterns, especially when decorated with different colors. It’s easy to do. Another perfect candidate is what the authors called “tile (1,1).” This figure is tiled periodically when combined with mirror images, but only aperiodically when mirror images are not allowed. So a perfect cookie cutter would have two of these shapes, one in the normal state and one in the reflective state.

The cookie cutter, based on the Hat discovered by David Smith, creates tessellated patterns with little wastage of fabric.

Smith and his collaborators also invented a category of curved, aperiodic monotiles called “spectres.” This can also be turned into cookie cutters, similar to the recently discovered soft sell. In each of these cases, if you are careful, you can cut the cookie dough with minimal rerolling or waste.

When you’re cooking or baking for the holidays, find a mosaic cookie cutter and get the kids involved, and the time you would have spent rerolling dough can be replaced with an introduction to science and math for your kids. You can spend it talking. In our case, our kids are already adults, but my collection of mosaic cookie cutters is exciting to share the wonders of math and science with when our grandkids arrive.

This is an opinion and analysis article and the views expressed by the author are not necessarily those of the author. scientific american.