January 8, 2025

5 minimum read

NASA’s Mars sample return program faces tough choices

NASA sees two paths to saving its floundering mission to recover material from Mars, but won’t choose between them until 2026

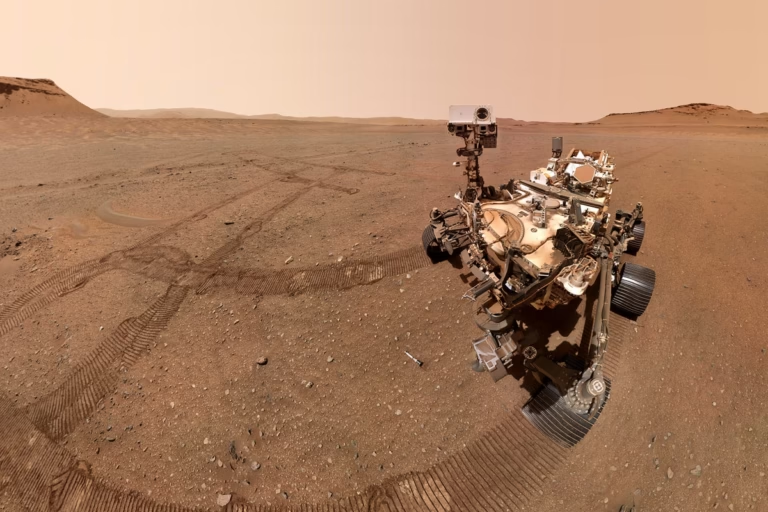

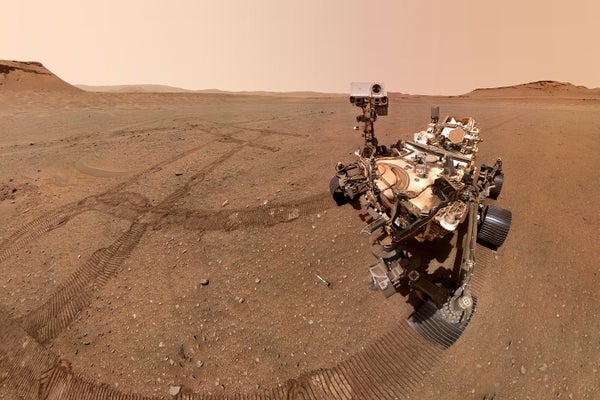

NASA’s Mars rover Perseverance is pictured in this selfie taken in January 2023 alongside several sample tubes dotting the landscape of Jezero Crater. The space agency is developing a new plan to recover most of Perseverance’s samples for study on Earth in the 2030s.

NASA’s troubled Mars sample return program is at a crossroads and likely to remain stalled until at least 2026, NASA officials said at a press conference Tuesday.

The effort, colloquially known as MSR, has been a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) for decades. It is a cornerstone of the United States and Europe’s near-term interplanetary science and exploration efforts, and is widely seen as a first step toward more ambitious human missions to Mars and back. The start-up phase is already well underway. NASA’s Mars rover Perseverance has spent much of the past four years roaming around the vast ancient lakebeds and river deltas of Mars’ Jezero Crater, where some of the 43 cigar-sized Mars rovers I have packed samples into. Titanium tube installed inside the ship. Scientists say analyzing these materials will at least change our understanding of the solar system’s early history, when Mars was warmer, wetter and perhaps more habitable. states. And in principle, the samples could even lead to the first-ever discovery of extraterrestrial life.

NASA’s original MSR plan envisioned launching a new lander around 2027-2028 to bring this precious cargo to Earth in the early to mid-2030s, as hoped. It will meet Perseverance on the Red Planet and transfer the sample to a canister inside the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV). The MAV will lift off from Mars, rendezvous with an ESA-provided Earth-return orbiter in space, then carry back a sample container and slowly swoop down to the planet’s surface via parachute.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. Currently subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

But the complex plan came under political pressure in September 2023, when a formal reassessment revealed that the estimated cost of the MSR had ballooned from about $4 billion to a budget-busting $11 billion. and faced financial headwinds. All in order to bring the precious samples back to Earth. U.S. lawmakers threatened a complete cancellation, and NASA Administrator Bill Nelson put MSR on hold, causing staffing cuts and exacerbating NASA’s fears. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the space agency leading the MSR program; Meanwhile, NASA began soliciting proposals for new programs not only from outside commercial companies but also from within itself. Last October, the space agency formed an independent strategic review team to evaluate the 11 accepted proposals and chart a path forward.

Tuesday’s briefing revealed the results of that independent evaluation, which presented two potential options for a faster, cheaper MSR. Both aim to save costs by transporting less mass to Mars. It also equips the sample recovery lander with a simpler spare robotic arm left over from Perseverance’s development, and redesigns the MAV to use a compact radioisotope power source rather than more finicky solar panels. They also share certain corresponding features. The first option for installing a sample recovery lander on Mars would employ an enhanced version of a proven technology: the JPL-developed hovering “sky crane” platform that landed the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers. I guess I will. The second option would instead transport the sample recovery lander to the Martian surface via an as-yet-unspecified commercial heavy lift vehicle, which is being developed by companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin. It is most likely some kind of giant rocket.

“Both of these two options create a much simpler, faster, and cheaper version than originally planned,” Nelson said at the briefing. He said the sky crane approach would cost between $6.6 billion and $7.7 billion, while the commercial heavy-lift option would cost between $5.8 billion and $7.1 billion. ESA’s cargo orbiter could be launched from Earth in 2030, followed by NASA’s sample-collecting lander in 2031. The return to Earth could be as early as 2035 or as late as 2039.

However, Nelson said that, citing the need for more detailed engineering studies, budget uncertainty and deference to President-elect Donald Trump, NASA will not be able to decide between the two options until mid-2026. He said he would not choose it. And to keep the program on track, he added, Congressional appropriators must allocate at least $300 million to MSR in the current fiscal year. This amount would need to be maintained “every year (of the program)” going forward. ”

“I think it was the responsible thing to do not to give the new administration the only alternative,” Nelson said. ”

Nicola Fox, deputy administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, expressed optimism about the new program at a press conference. “I’m excited about both paths,” she said. “I think if we leverage all of our partners, our international partners, our commercial partners, and the incredible expertise of NASA, we can really make this happen.” She said the Perseverance rover will be “on Mars.” “It’s extremely healthy and stable,” and has already filled 28 titanium tubes with carefully selected samples of Martian rock, sediment, and air. Ten of these tubes are stored on the surface as backup in case Perseverance fails and cannot reach the recovery lander. The new plan calls for abandoning them in favor of bringing back larger quantities. The 30 tubes are hidden within Perseverance and are expected to be fully operational by the 2030s. Meanwhile, Fox said, “There are still 13 attractive tubes left unfilled. … We are very confident that we will be able to return all 30 samples by 2040.” And…for less than $11 billion.”

To MSR chief scientist Meenakshi Wadhwa, a Mars expert at Arizona State University, this push for more samples sounds exciting. “We are particularly pleased that the goal is to recover as many as 30 sample tubes by 2035 at the earliest,” she says. These samples “will answer fundamental questions for us humans and revolutionize our understanding of planet formation processes in our and other solar systems.”

Harry McSween, a longtime proponent of Mars sample return and a professor emeritus at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, also emphasizes the importance of recovering as much material as possible. “Reaping the scientific benefits from MSR requires not only collecting samples from anywhere on Mars, but also carefully selected samples collected from carefully chosen sites to address important questions. It’s necessary,” he says. This points to what may be the strongest motivator for continued political support for the MSR: the much simpler “grab and go” retrieval of some number of samples from a single sample. This is in sharp contrast to competing sample return efforts by China, which appear to include a mission. , an easily accessible spot on Mars. This could put China first across the finish line in the conceptual race to return Martian material to Earth, but it would come at a significant scientific cost.

Some are less sure that Tuesday’s announcement is something to celebrate. “We’re glad MSR wasn’t canceled, but we need to make decisions quickly and move forward,” said Casey Dreier, head of space policy at the Planetary Society. “I’m concerned that the MSR has been in limbo for so long. The path forward they’ve promised us is nothing more than more research. NASA will decide whether to go ahead with the mission and… We need to decide where to go from there.”

For Dreier and others, the choice appears to be between a skycrane, likely a JPL-led approach, or a “use what you know” approach, or reliance on the more uncertain and difficult innovations of commercial enterprises. . As for the latter, “obviously[NASA]is talking about SpaceX, which is the only viable company to take on this capability through Starship,” Dreier said. SpaceX is developing a fully reusable heavy-lift vehicle. “However, that requires Starship to be operational and reach Mars.” By using Starship, “we can make a stronger case for MSR to serve as an unmanned demonstration mission for future human Mars operations.” Dreyer added. That could integrate this high-priority NASA science mission with the space agency’s broader goals for human spaceflight.

“I think there’s a path there,” Dreyer concluded. “But that still assumes a lot of unknowns.”